Looking out from the 11th floor of Glasgow’s Savoy Centre you can see half the city laid out before you. From the east end to the city centre, it is stacked up like Lego bricks. Tall buildings, low buildings, old buildings, new buildings.

Good buildings and bad buildings too. But which is which? What category does the one I’m standing in alongside Alan Stewart fit?

He would say the former. Stewart, an architect who divided his childhood between Mexico, where he was born, and Scotland where he went to school and later university, has co-written a book called Braw Concrete. Created in tandem with Peter Halliday, it’s a celebration in words and pictures of the postwar architecture of Scotland’s biggest city; a paean to its brutalist buildings and the charisma of concrete.

The allure is perhaps not widely shared but is, according to Stewart, more common. Now 50, 60, 70 years on from when they were originally built, brutalist architecture has a growing fanbase.

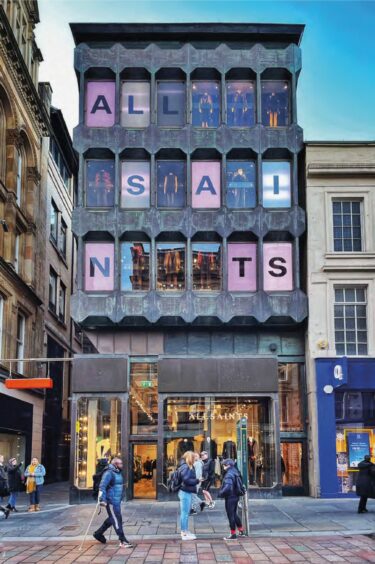

But what is the reality? Eyesores or eye candy? Journeying from the Stakis Ingram Hotel to the Hunterian Art Gallery and Mackintosh House in the city’s west end, it takes in such monumental structures as Hillhead Library, the Ministry of Defence’s Kerntigern House, Royal Exchange House (aka 100 Queen Street), Empire House, and even the M8. Oh, and the building Stewart and I are standing in this afternoon, with its monumental scale and ribbed concrete exterior.

For some, these buildings are monstrous carbuncles, but the authors believe they are audacious examples of postwar architecture and as such deserve to be recognised and where possible preserved.

“I’ve never seen a cluster of postwar architecture as of good quality as I have in Glasgow,” Halliday suggests when he joins us on Zoom from Shropshire. Unlike Stewart, Glasgow is not a city he knows well. But on a weekend trip a year ago, he says, he was blown away by what he found.

“I am an enthusiast in postwar architecture anyway and I was immediately beguiled by the place in terms of the swagger of it.”

Stewart’s love is similarly emphatic. “I think it’s the purity, the honesty in those buildings. They are concrete and you know that they are concrete because you can see it, you can touch it.”

Of course that concrete reality is exactly the problem for those who hate it, but Braw Concrete makes the case for the vigour and ambition of postwar architecture and sees Glasgow as an exemplar of the best of the era.

“It reminds me of a time of optimism in the postwar consensus where people were literally trying to build a better world; with decent housing, with state institutions, with universities,” Halliday argues.

And some of the best examples can be found in Glasgow, the duo argue, thanks to the efforts of local architects and visiting architects. Halliday cites the copper-clad BOAC Building in Buchanan Street, the work of Isi Metzstein and Andy MacMillan for Gillespie, Kidd & Coia. Metzstein and MacMillan are widely regarded as giants of Scottish postwar architecture. Perhaps more contentiously, he also suggests the Anderston Centre, or what remains of it, the work of visiting architect Leonard Watson who worked for Richard Siefert.

“Try and take a fresh look at it,” Halliday suggests. “Of course it’s not got a great reputation for all sorts of reasons, but it’s by a practice called the Richard Siefert Partnership and they’ve done the most emblematic postwar buildings anywhere in the UK; Centrepoint in London is Siefert.”

Stewart chips in with the College of Building and Printing (aka the Met Tower), which dates back to 1964. “It’s tall and slender in the east-west direction and it’s bold towards the city. It’s almost presenting itself,” Stewart points out. It’s also known, he adds, as the “People Make Glasgow building”, referring to the huge logo to be seen ranged across its top floors.

“This is an impactful building,” Stewart notes approvingly. “It’s on postcards.”

There’s no doubting the ambition of postwar architecture but in the area of public housing in particular it was often found wanting. The story of Glasgow’s Red Road flats, built between 1964 and 1969 and once the tallest residential structures in Europe, was all too typical.

Originally seen as an answer to the problem of slum housing, concerns about asbestos, antisocial neighbours, vandalism and broken lifts began to tarnish their reputation in the 1970s. By 2015 they were all demolished.

“I think there were very few people who complained when they moved from a slum dwelling with no inside toilet to a brand, spanking new flat,” Halliday suggests. “Yes, of course, there were residential developments from that era which were shockingly bad. But there were an awful lot that were amazingly good.

“You’ve got the Barbican Centre in London. No one’s complaining about that. What’s the difference? The only difference is that it was looked after.”

“It’s the stigma, isn’t it, Peter?” Stewart suggests. “That really quick succession of building tall, building quick, building in concrete. Social and economic issues really stigmatised that whole movement.

“So now you talk about tall buildings in Glasgow and everyone shuffles in their seats. It is a mindset.”

The truth is high-rises sometimes suffered from poor construction and sometimes from the withdrawal of investment and the collapse of working-class employment and incomes during the 1980s. This is a familiar story when it comes to postwar architecture. In the UK at least.

“You look at some of the postwar buildings in mainland Europe that were taken care of. It meant that they had that longevity and that longevity becomes cherished,” Stewart suggests.

Maybe now in the UK, too. Ironically, some of the high-rises that did survive, such as Park Hill in Sheffield, have now been redeveloped and houses on the estate are keenly sought after by young professionals in the 21st Century, a new twist on upward mobility.

Still, it’s a reminder that postwar architecture can be reclaimed and repurposed. The Savoy Centre is an example of that. There are now many companies working in the building in the city’s famous Sauchiehall Street. “It’s come back to life,” Stewart suggests. Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands, the architectural practice he works for, is one of them.

But while it is technically possible to redevelop buildings such as the Savoy Tower for 21st-Century use, it is also expensive. Then again, to knock them down and start again might have an even greater environmental cost. Concrete holds carbon, much of it in the foundations.

“It’s like an iceberg, a lot of the embodied carbon is in the basement,” Stewart points out. In the circumstances it may make more environmental sense to redevelop rather than demolish.

Braw Concrete makes this point. But it also wants to celebrate a moment in time in Glasgow’s architectural history that should not be overlooked.

“It is part of the heritage of the city, part of the story of the city,” suggests Stewart.

“It is the bold optimism, the audacity of it,” adds Halliday. “The idealism of it, maybe misplaced maybe naive, but it was evidence of people who were literally trying to build a better world.

“I’m not sure we see that as often as we would like to.”

Braw Concrete by Peter Halliday and Alan Stewart is published by The Modernist. the-modernist.org

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM