It was one final warning. It would be ignored and, within hours, the world would go to war.

The front page of The Sunday Post of September 3, 1939, spelled it out. “German forces must withdraw” was the headline above a story beginning “Last night Britain and France still awaited Hitler’s reply to the final warning that the guarantee of Poland will become operable unless German troops are withdrawn”.

Hitler had invaded Poland two days before and, when Neville Chamberlain’s Saturday night ultimatum delivered in a packed House of Commons was ignored, the Prime Minister declared war the next day. It came as no surprise.

Plans were already well under way – gas masks for all and huge spending on munitions. The same front page revealed “All men between 18 and 41 to register” and public spaces, like Princes Street Gardens, in Edinburgh, had been dug up for air-raid shelters.

Swathes of Scotland were carved out for airfields, sea defences and seven emergency hospitals to cater for anticipated casualties.

Tom Johnston, the regional civil service commissioner, and later Scottish Secretary in Churchill’s coalition government, reported the evacuation of 140,000 children away from Glasgow, Edinburgh and Dundee had gone smoothly.

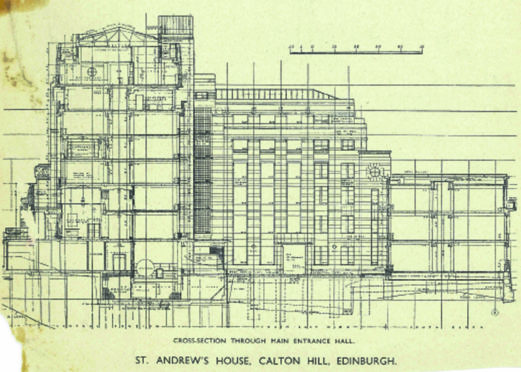

All of this was co-ordinated by the Scottish Office from its HQ in the capital, St Andrew’s House, on Calton Hill. Plans for the building’s formal opening by the King and Queen were cancelled along with the orders from Dobbies to provide rooftop gardens.

The art deco landmark was quickly blackened by soot and grime from the railway below – electrification was talked about by 1940 but took another 50 years – and the modernist design apparently appealed to Nazi planners, who had it earmarked as their potential base after Britain fell.

Other articles in The Sunday Post that day struck a mixed tone of trepidation for the future and reassurance that normal life continued.

They included the Francis Gay column reporting: “In this time of wars and rumours of wars…there is yet peace for those who will carry on the week’s work with willing heart and calm conscience.”

The first article to clear the wartime censor was an account of how we could help Poland: “Put out of your mind Nazi nonsense about a ‘lightning war’ in which one crushing German blow would bring the Allies to their knees.”

It was optimistic but, pretty much, wholly wrong.

Armchair strategists were still locked in the past. The war to end all wars only brought peace for 20 years. It didn’t end with the Armistice in 1918, only with the peace of Versailles.The last to die were nine German sailors shot dead and a further 16 wounded by the Royal Navy under a flag of truce in June 1919 as the Kaiser’s fleet was scuttled in Scapa Flow. They were buried on the island of Hoy.

There was a more positive legacy from the carnage – antibiotics. Alexander Fleming and Gerhard Domagk had witnessed the dreadful toll from battlefield wounds.

Fleming’s discovery of penicillin in 1928 only reached mass production in 1943. Domagk produced the first antibiotic to be widely used. Prontosil, derived from a chemical dye, the first of the sulphonamide drugs, became available from 1935 and saved the lives of countless mothers who had contracted sepsis giving birth.

The sharpest ever fall in maternal mortality in Scotland took place between 1939 and 1941 – thanks mainly to a drug from Germany.

In October 1939, Domagk was awarded the Nobel prize for medicine but Hitler stopped him from collecting it and the Gestapo detained him for a week. By that time the real war had begun.

The first Nazi bombing raid came over the Firth of Forth on October 16. Many watched the dogfights over Fife, Edinburgh and East Lothian.

Contrary to myth, the Forth Bridge was not the target. Hitler had given specific orders to attack Royal Navy ships in the Forth and avoid civilian casualties – at this stage of hostilities there was still the prospect of a negotiated settlement.

Although not reported at the time, the Forth raid was partially successful. Two ships, HMS Edinburgh and HMS Southampton, suffered damage and 16 crew members on HMS Mohawk were killed.

Jock Kerr, one of the Mohawk survivors, later recalled there were no warning sirens of the attack.

Many of the Luftwaffe aircrew had previously served in the Condor Legion supporting Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Its most notorious attack was the bombing of Basque civilians in Guernica.

One of them was Hans Sigmund Storp, who deliberately ditched his Junkers 88 dive bomber off Gullane to save his crew after being hit by Spitfires. A fishing boat picked him and his crew up – saving their lives. Storp was so grateful he gave the skipper, John Dickson, his Luftwaffe gold ring.

There was a common bond between the aviators on both sides – all nervous young rookies with brand-new aircraft. Spitfire crews from 602 (Drem) and 603 (Turnhouse) auxiliary squadrons visited and took gifts to their wounded Luftwaffe counterparts in hospital.

Newsreels had a field day stressing the RAF’s first successes, but they also echoed a sense of chivalry, giving equal respect at the funerals of German airmen and British sailors.

Scottish mothers even left wreaths for the German boys.

The time for chivalry scarcely lasted the first six weeks of war. Six long years were ahead, years of harrowing loss and sacrifice, of lives taken, families shattered and cities rubbled.

However, as The Sunday Post of September 3, 1939, reveals, in page after page, charting the apparently inevitable march to international conflagration alongside everyday news stories and features, life goes on. Hope endures and life goes on.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe