They are tales of ferocious derring-do and of new worlds to conquer and always, always told through the eyes of the men doing the gung-ho adventuring.

Now, inspired by her own husband making a bid to climb Everest, author Katherine MacInnes has told the story of Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s epic attempt to reach the South Pole from the perspective of the wives and mothers, left behind with only undimmed hope and gnawing fear.

MacInnes spent the best part of a decade immersing herself in the story, travelling the world, digging dusty papers from the depths of museum archives and reading lovingly preserved diaries and letters.

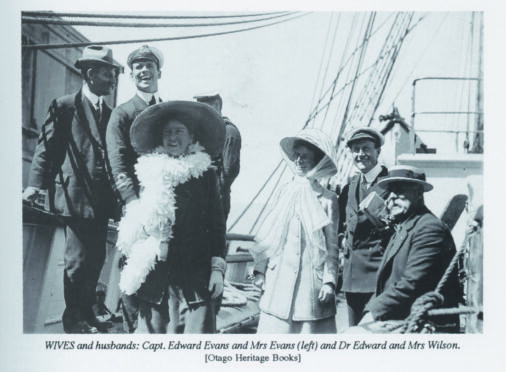

She believes Kathleen Scott, the leader’s wife; Caroline Oates, the mother of Lawrence Oates; Emily Bowers, mother of Henry “Birdie” Bowers; Oriana Wilson, partner to the expedition’s doctor, Edward Wilson; and Lois Evans, wife of Edgar Evans, another member of the expedition, have been resigned to nothing more than footnotes or captions in the history books despite their key roles both before and after the ill-fated adventure.

“I started my research with three small children, one still crawling,” said MacInnes. “Frankly, archives were a refuge of grown-up civilisation in a sleep-deprived, nappy-brained world. I suppose I also wanted role models without having to ask awkward questions of living explorers’ wives.

“The most difficult part of tracing the lives of the women was that four of the five were almost self-erasing – burning letters, rubbing out pencilled diary entries, perjuring themselves to lie about the existence of records. To start with, it was a question of filling in the gaps through audio recordings in obscure libraries, travelling to New Zealand and posting features in the local newspapers to see if anyone had received letters from them.

“The process took about a decade, partly because of the nappies, and partly because it required time to establish an extensive network of contacts to glean the letters from the recipients rather than, as was the case for their menfolk, through established archives.”

The result of MacInnes’s determination is her book, Snow Widows, published this week. Written as a present-tense re-enactment, punctuated by key dates and the location of each of the women, she explores the months before and during the Terra Nova Expedition to Antarctica, which took place between 1910 and 1912, as well as the many months after Scott and his crew tragically perished in the cold.

Rather than writing a traditional non-fiction account, MacInnes admits she wanted the reader to form a connection and bond with the female characters, understanding the fear and uncertainty they lived with every day.

She said: “Everybody knows the end of this story. So, my challenge was getting the reader to suspend their belief – to believe that, for these women, it hadn’t happened yet. I tried to put the reader in their position.

“Back then, in the first decade of the 20th Century, there were no mobile phones. The British Empire was connected with under-sea cables through which telegrams could be sent but there was no cable laid to the Antarctic. This is why it took so long for the Terra Nova to be able to get through the sea ice to receive the tragic message – the Snow Widows learned the news 11 months after their men had died.”

The decision to write in present tense was also inspired by a meeting with Wayland Young, Kathleen Scott’s son from her second marriage after Captain Scott’s death. MacInnes said: “I met Wayland and he started speaking of the past in the present tense – it was as if he could see it all happening. He would say, ‘Well, my mother is over there, the light’s on here, and this is where the sculpture table is, the book is open here…’ It was unbelievable.

“I got goosebumps because it really felt as if history was still there in the room. From his memory, it absolutely came alive. I thought if I can do that for other people with this story it would make it much more real.”

Although the Snow Widows weren’t physically there on the Ross Ice Shelf in 1912 – where Scott ultimately discovered he had been beaten to the South Pole by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen five weeks previously – MacInnes insists the many biographies written of the explorers are incomplete without the perspective of the women.

“What I find fascinating is the men were in the same hut, the same tents, and yet they wrote things to their wives that they didn’t say to the person in the sleeping bag next to them,” said MacInnes, who will discuss her book at the Aye Write! Book festival in Glasgow next month. “They were their confidants, the person who formed their opinion and their own attitude to resisting the terrible, terrible tragedy of the situation at the time. So, they are a real insight into the character of the men.

“They absolutely shaped the story, particularly, perhaps, Kathleen Scott. At the time, because the Norwegians got there first, there was a lot of bad feeling among some people about the fact the Pole had been ‘stolen’ from the Brits. However, Kathleen was determined to bear no ill will.

“She wanted to praise the Norwegians and to say it has been a fair race, and there was no blame anywhere – it was just bad luck and bad weather that meant that Scott hadn’t managed to get back.”

In the wake of the recent discovery of the Endurance, the lost vessel of fellow Antarctic pioneer Sir Ernest Shackleton, which was crushed by sea ice and sank two years after Scott’s doomed adventure, MacInnes hopes the renewed interest in early 20th Century explorers will mean the last pieces of the ship Terra Nova will be brought into public view.

Unlike the RRS Discovery – which carried Scott on his first highly successful journey to the Antarctic, and is now preserved as a museum in its home town of Dundee – the Terra Nova went back into commercial use as a whaler after the expedition party didn’t make it home. It was sunk in 1943, and all that remains is the ship’s figurehead, which MacInnes visited in storage as part of her research.

She says being able to see artefacts from the adventure, including the many diaries and letters preserved by the Snow Widows, helps to keep the tragic story alive.

“In Harry Potter there is a portkey, which is an everyday object you touch and you go through to another world – that’s how I feel these about these artefacts,” said MacInnes. “Of the ship, the Terra Nova figurehead is the only thing that survived. It is actually there to see and yet, it’s in storage not on display.

“It was moving for me to see it in person. I really want to make a case for it coming out of storage so more people can see it.”

For now, however, she hopes her reframing of the story will help the world see the full picture of Scott, his companions and the women whose lives were forever changed by the drive to discover the world. She said: “Snow Widows is the reframing of the world’s best ‘ripping yarn’ – it should be a page-turning, total immersion that provides a sense of wonder at the resilience of these women.”

Snow Widows: Scott’s Fatal Antarctic Expedition By The Women Left Behind, William Collins, £20, is published on Thursday

Katherine MacInnes will be at Aye Write at the Mitchell Library, Glasgow on 14th May, tickets available from Aye Write

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe