She could have been Scotland’s Enid Blyton if her bestselling children’s books had not been lost in the Blitz.

Ann Scott-Moncrieff’s Aboard The Bulger, a huge success when it was published in 1934, when the author, only 20, won rave reviews both here and in America. She was on the cusp of international fame when her publisher’s Methuen’s offices next to St Paul’s cathedral were razed to the ground on 29 December 1940 as bombs rained on London.

Tens of thousands of thousands of incendiary bombs famously missed their target, the cathedral, only to fall on Paternoster Row, destroying more than five million books in the storage offices of four publishers.

Aboard The Bulger – Ann’s first book – was among them and few copies were ever in circulation as a result. Her second book, The White Drake and Other Stories, was also a victim of the firebombing, while her third book, Auntie Robbo, published in America by Viking, was lost when the ship carrying copies across the Atlantic was torpedoed by a German U-boat.

But today, 80 years later, the book has entered a new chapter, as Ann’s work has been saved by her publisher granddaughter, Jean Findlay. Her independent firm, Scotland Street Press, is bringing out Aboard The Bulger, which features the tale of an evil witch, in time for Halloween.

“Ann died when she was only 29, cutting short a brilliant writing career,” said Jean. “If her books had not been destroyed in the war and if she’d lived, she would have been as popular as Enid Blyton.”

“There were only a few advance review copies of Aboard The Bulger in circulation before the War. The majority of the stock of hardback copies that were stored in the publisher Methuen’s storehouse were destroyed in the Blitz.

“There are a few original copies still in circulation in second-hand bookshops but they are rare and can fetch up to £200.

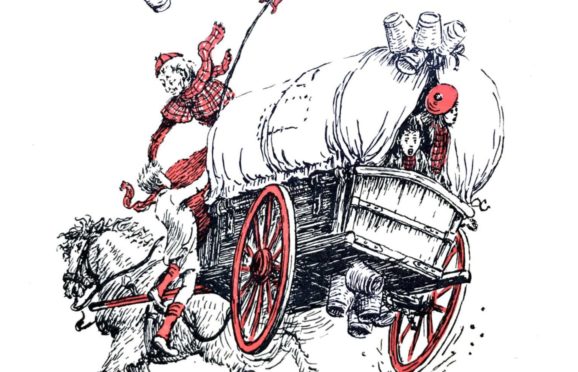

“I have author copies of all three of Ann’s children’s books handed down to me, so we worked from these to retype them and reprint them as softbacks, redesigning them as a series. We spent two years tracing the descendants of the illustrators to get permission to reproduce the drawings by CL Davidson, Christopher Brooker and the famous Russian illustrator Feodor Rojankovsky, known as Rojan.”

All three books were originally published in hardback. Many of the copies of Auntie Robbie, which was published by Viking in the US, were sunk in a German torpedo attack when they were being shipped to the UK.

Jean grew up being read her gran’s three children’s books on her mother’s knee and went on to read them to her own children.

“I never knew my grandmother but felt I got to know her through her books – you can tell a lot about an author from their writing. Her books have her spirit of rebelliousness and sense of humour; they are wild and savage,” added Jean, one of eight children. “Growing up, I loved her books as they’re funny and lively, not soppy or sentimental at all. She has a great turn of phrase. The book is about five children who escape from a cruel orphanage, run away and steal a steamboat, The SS Bulger, which they sail around the Outer Hebrides. They land on the island of Borg where the villagers believe there is a witch called Cuddyreek who inhabits an enchanted isle.

“The story has timeless appeal as it’s about children who get together to live their own lives and have the freedom away from adult supervision togo on adventures,” added Jean. Ann, brought up on ancient legends she’d heard on Orkney, wove into the book tales of witches who caused mischief and phantom islands that were said to mysteriously appear and disappear into the waves.

She also drew on her own background when she wrote about the children taking charge of a steamboat – her uncle manned the St Ola, the ferry across the Pentland Firth between Scrabster and Stromness Orkney.

Born Agnes Shearer in 1914, Ann’s short life was packed with excitement and adventure. She became a reporter on The Orcadian when she was 16 before moving to Fleet Street to work for The Daily Mail two years later. It was there she met George Scott-Moncrieff and they became engaged.

The couple moved back to Scotland and were married in 1934 when she was 20 and went to live in Stobo near Peebles, in a tiny cottage let out in return for work on the farm. In that first summer Ann finished her first book for children, Aboard The Bulger and the following year her second, The White Drake and other Stories, which will be republished next year as Firkin and the Grey Gangsters.

When the author Eric Linklater went to visit the impoverished young couple in their two-room cottage with barely room for a bed, his wife asked where they kept their clothes.“We wear them,” replied Ann, with dignity. They later moved to Temple, Midlothian, where Ann contributed to newspapers and magazines, and short stories to BBC Scotland, while having three children. Ann’s daughter, Lesley, 83, said: “My parents were part of the group of writers and thinkers before and during the war who were later dubbed ‘the Scottish Renaissance’, with friends such as the poets Edwin Muir and Hugh MacDiarmid. Ann and George were both writers, but my mother made more money.

“But Ann was increasingly unwell, battling ill health, the exigencies of looking after a young family in war-time and writing to deadlines, often staying up all night to work.”

Ann died when Lesley, her oldest child, was only five. Recuperating from a hospital procedure, Ann went to stay with her aunt in Nairn. A keen swimmer all year round when she was growing up in Orkney, Ann went into the sea one night and drowned. Her body was never recovered. “She just disappeared. She wasn’t well and would probably now be diagnosed as bipolar, but I don’t believe she took her own life,” said Lesley. “She was full of enthusiasm and loved life,” added her daughter, Lesley. “She was unconventional for a woman in the 1930s.”

Aboard The Bulger is published by Scotland Street Press

From the book

Ann Scott-Moncrieff delved into her own childhood on Orkney for Aboard the Bulger to write vividly about island life.

Here’s an extract:

They learned to fish and spent long hours in the Baby Bulger or a Borgian yawl on sunlit evenings, and moonlit nights. Sometimes it was with slender wands dipped deep in the water for sillocks, sometimes with rods poised ready for the surface storm of the mackerel troops, or again with haddock lines paid over the gunwale.

Afterwards they would row home, spray-drenched, pleasantly weary, ravenously hungry; and, no matter what the indigestible hour, fry their fresh, curling catch on the galley stove. They would eat them with their fingers; crouching and steaming round the fire; squatting on deck when it was fine, to see the moon better and smell the adventurous night air.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Supplied

© Supplied © Supplied

© Supplied