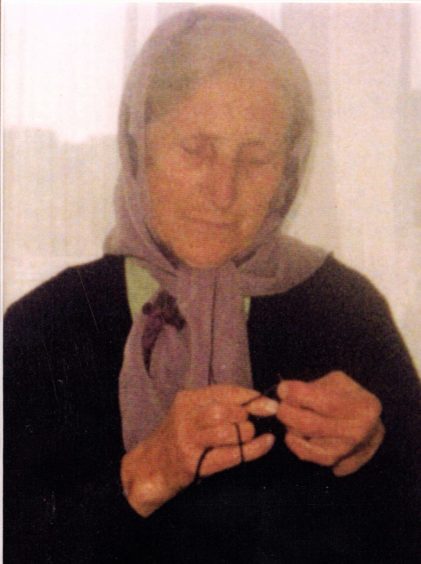

When Margaret Anne Elder sits down with her knitting needles, she always thinks of her late grandmother.

With each stitch and purl, click and clack of the needles, not only is the 52-year-old weaving together a rich pattern of wool, she is also keeping her family’s legacy alive by paying homage to an age-old tradition that, without her dedication, could fade from memory.

Creating everything from jumpers and hats to scarves and shawls, Margaret Anne uses unique patterns and techniques first developed at the turn of the last century by a band of women known as the “Herring Girls” – which included her paternal grandmother, Marion MacLeod.

“I watched my grandmother knitting every moment of the day,” said Margaret Anne, who was born and raised on the Isle of Barra, in the Outer Hebrides. “Often, when she walked from her home village to the shop or post office she could knit one sock there and one on the way back. She was a big influence in my life, and I spent a lot of time with her until she died. She left me with so many memories, as well as her skills, which have been passed down from generation to generation.

“But there’s no formal pattern to these jumpers – I’ll say to some- one, ‘OK what size are you from your wrist to underarm?’ and go from there. I’m really lucky the skill has been carried on in my family, passed down through my father’s side.”

From the 18th Century until the outbreak of the Second World War, women from across the east coast of Scotland followed herring trawler ships as the catch migrated to new breeding grounds, and were employed on land to gut, salt and pack each day’s catch. Working for up to 15 hours a day in gruelling conditions, the Herring Girls often spent months away from home and, in their spare time, kept up their spirits by singing, dancing and knitting items to send back to their loved ones.

Designed to reflect their home port, each knitted piece would feature anchors, ship wheels, marriage lines and true lover’s knots, which worked to form a pattern that was uniquely identifiable to each community.

Margaret Anne said: “The garment is knitted in one, and there’s no sewing, so the jumpers take a long time. There’s a lot of passion and a real story behind each pattern. A lot of the time, when the Herring Girls made jumpers, it was for someone they really appreciated. To put that amount of work into something was – and still is – really special.”

Margaret Anne, having grown up hearing tales of these formidable women, and learning their designs from her grandmother, always knew she wanted to preserve their legacy. But it wasn’t until she moved back home to Barra, after four years working on the mainland, that she finally made a plan to spread their story far and wide.

After initially making a few items for friends and family, Margaret Anne formed the Herring Girl Knitwear range, a collection of fisherman’s jumpers (or guernseys), scarves, shawls and hats handmade from traditional patterns by just five knitters.

Margaret Anne said: “I had been knitting items and giving them away, but people used to say, ‘Why aren’t you selling these?’ It wasn’t until I sat down and thought about it, I realised wanted to revive the traditional knitting skills, but also tell the story of those women. So, last year, I started by knitting garments for the local choir, who wore them to the Royal National Mod. People kept asking where they got their jumpers, while at home our web page went live, and now here we are.”

Margaret’s beautifully crafted knits are now sold on the islands and around the world online and will soon be stocked by retailers across Scotland.

As well as intricate patterns, each item features letters to signify different fishing ports, with CY for Castlebay on Barra, SY for Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis, and BRD for Broadford on Skye.

Each of Margaret’s knitters has adopted a symbolic code name, which customers can use to identify work. “The knitters have all chosen the name and registration number of a fishing boat from their family,” said Margaret Anne, who is known as “CY Grian nan Oir” after her home township of Bruernish and grandfather’s boat.

“Plus, if you buy something from the collection and it’s posted from Barra, it’s also wrapped in silver tissue paper to represent the silver darlings, and we include a little slip of paper that tells you more about the pattern and the fishing industry. It’s then wrapped in brown paper and string, as it would have been in the days of the Herring Girls. When it arrives at the door, I want people to understand the significance and history – it’s about so much more than just a jumper.”

The Honest Truth: New project reveals why ganseys were the real fisherman’s friend

Margaret Anne hopes to continue growing her small company, keeping island culture alive and finally giving the Herring Girls the recognition they deserve. “From my gran’s character, and what you hear other people say about the Herring Girls, you get such a feel for them,” said the mum-of-four and gran-of-two. “They were a unique set of women, who don’t seem to have been celebrated as much as they deserve.

“They were a formidable bunch of women, and my granny certainly was until the day she died. In island culture, the Herring Girl is a hardworking, strong woman who was not scared of hard graft. I hope, through the collection, we can pay tribute to their resilience and thank them for keeping these traditions alive for us to take on.”

They were formidable, working long hours in hard conditions

By Calum MacNeil, Isle of Barra historian

The Herring Girls played a pivotal role in the islands from the 1860s right through to the Second World War.

There were usually three women to a crew – two gutters and one packer. To give you an indication of the amount of folk employed, between three stations on Barra, in 1887 alone, there were 1,466 women working at gutting and packing the herring.

On a good day, a three-woman crew would gut between 20 and 30 barrels, which would earn them between five and six shillings per barrel each. That was reasonable money for them.

Then the process of “topping up” would add an extra threepence an hour to their wage – the herring would settle once packed, so when the cooper took the lid off, the women would have to repack the fish and “top it up” to make sure it was full.

In 1936, the Herring Girls actually went on strike while working in Great Yarmouth because they thought threepence wasn’t enough for the extra task. They had the curers over a barrel, really, because the herring had to be cured or it would go off – that wasn’t in anybody’s interest. The strike ended when they successfully secured a raise to sixpence an hour.

They worked long hours in hard conditions, but it was the only work available to them, so they didn’t really have a choice in the matter. But they also appeared to have enjoyed the job, and there was a lot of camaraderie between the girls – and they made friendships that lasted a lifetime.

When they got time off they would enjoy themselves by setting up impromptu ceilidhs in their huts – nothing more than one room with a stove and bare walls – and they would invite along the local fisherman they knew.

They were certainly formidable women, but they had to be. The men folk, invariably, were off at sea, so the women were left to look after the croft and the family – and they had to instil the discipline.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © Alamy Stock Photo

© Alamy Stock Photo