Stripping our world of scent can make it a strange, discombobulating place.

In the first few weeks of the pandemic, when we were all losing our everyday freedoms, Paola Totaro suddenly, frighteningly, became one of the Covid sufferers who lost her sense of smell.

The writer began frantic Google searches to understand why she could no longer enjoy the scent of her favourite perfume or drink white wine that didn’t taste like mild, odourless vinegar. Like an estimated 40% of adults in the UK, Totaro had lost her fifth sense after Covid but at the time, it wasn’t yet an official symptom and her freefall into a “sensory vacuum” felt overwhelming, almost cruel, as the few pleasures left to her – food, drink and walking outdoors – had lost all their joy.

“I was really worried it would never come back,” explained Totaro. “I had started to hear anecdotal evidence that it was happening to others and I was lucky because I could get in touch with my brother (an ICU specialist), who was working in Australia and hear lots and lots of anecdotal medical response.

“But we had absolutely no idea of whether this was final, whether this virus that was killing people might actually kill our neurons, too. It was like walking in a dark tunnel because I had absolutely no idea whether it would come back and, if it did, when and how. It was like walking blind.”

While she had lost the ability to smell, she gained a new appreciation for the sense that French neuroanatomist and anthropologist Paul Broca once famously described as the “poor cousin” of touch, sight, hearing and taste, leading to a greater understanding of how scent and odour are inextricably linked to memory, emotion and many more aspects of everyday life.

She continued: “It really wasn’t until I lost my sense of smell that I realised how it absolutely touched everything I do, from my work and how I relate to people to how I enjoy a dog walk and literally how I perceive the world.”

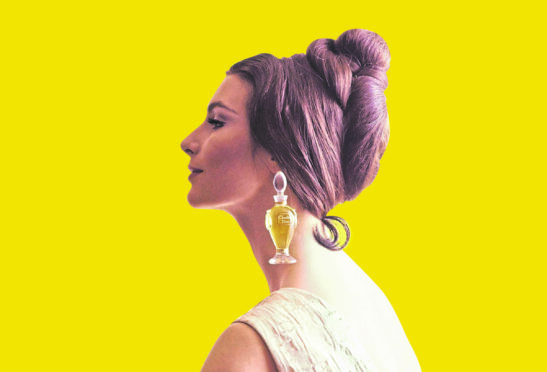

Fascinated by the implications of her loss of smell – officially called anosmia if lost completely, and hyposmia when the loss is partial – Totaro began detailed research into the body’s least understood sense, resulting in her book, On The Scent, published this week.

Exploring her own journey from loss to partial recovery some six months later, the fascinating book, co-written with her husband, Robert Wainwright, also delves into the historical importance of scent, as well as the latest scientific research into how an absence of smell can be linked to everything from early detection of Parkinson’s disease to an increased risk of depression.

“I realised early on that to understand why smell had become the ‘poor cousin’, we had to look back in history to see how we understood disease in early science and medicine,” explained Totaro, who was formerly the president of the Foreign Press Association in London, and began working on a PhD at Goldsmiths University in 2020. “Smell was the harbinger of bad things, then later good things. The cultural aspect of smell is fascinating, and it’s also sentinel of good health.

“I had no idea, for example, that the sense of smell could be a sentinel of Parkinson’s. That was one of my horrors because my dad’s got Parkinson’s. When my sense came back, I had this incredible relief that it wasn’t something that was permanent.

“The truth is, if you go to the GP and you suddenly say, ‘I can’t hear any more’ or ‘I can’t see any more’, my goodness, you would be sent off for a battery of tests. With smell, it’s like, ‘Oh, you’ll be all right’. It’s sort of a dismissal, isn’t it?

“But, with Parkinson’s, if you respond and take medication early, as soon as a sense of smell goes, your outcome and life expectancy and quality of life changes dramatically. Yes, it’s horrible to know early that you’ve got something that you might not have symptoms for but as science develops and medicine develops you might be able to manage those symptoms better.

“There’s so much to learn. We still don’t really know how smell works. We don’t really know how we get it back, and we don’t really know why it disappears.

“Smell is not just the molecule that enters your nose and attaches to the receptor. It is part of a fascinating process. When odour goes into your brain it bypasses the rational part of your brain and goes straight into that emotion centre, or that centre that collects and computes memory. So, there’s nothing more memorable than a moment that is attached to a smell.”

When describing the important and intense connection between memory and smell, Totaro points to the poet Marcel Proust’s description of his “involuntary memory” brought forth by dipping cakes into tea. “One of the most famous tracks in literature is Proust dipping the Madeleine into the tea and being transported back to that familial kitchen,” she said. “Everybody has their own Madeleine moment.”

From the book

William Wordsworth is best known for his seminal lyric poem, I Wandered Lonely As A Cloud, also known as Daffodils. But Totaro tells in her book how he cruelly suffered from anosmia, a condition that left him unable to smell the delights of the natural world

“The flower that smells the sweetest is shy and lowly.”

William Wordsworth, one of the great English Romantic poets, wrote these words in 1821. He was a prodigious walker who adored wandering the English countryside composing poetry about the glories of nature – but he could not smell the beauty he observed.

He penned four verses in one afternoon about the joy and beauty of daffodils, their colour and movement – flower heads bobbing and long stems waving as the breeze puffed across the water. But never once did he mention the smell that must have enveloped him as he passed through the golden field, a rich, narcissus-like fragrance that can polarise opinion as some perceive it as pleasantly musky or vanilla-ish while others liken it to raw onions, cat urine or even spoiled fish.

A search for the words “smell”, “scent”, “odour” and “fragrance” in a six-volume collection of his works published in 1865 and now digitised threw up just half a dozen uses. When he did describe smell, the word he fell back on was “sweet” – a quality that, even in anosmia, is recognisable by the tongue.

Wordsworth’s nephew, the Bishop of Lincoln, Christopher Wordsworth, observed that references to scent in his uncle’s poetry were based on what family and friends described to him: “With regard to fragrance, Mr Wordsworth spoke from the testimony of others: he himself had no sense of smell.

“The single instance of his enjoying such a perception… was, in fact, imaginary. The incident occurred at Racedown (Lodge in Dorset), when he was talking with Miss H (his fiancée Mary Hutchinson), who coming suddenly upon a parterre of sweet flowers, expressed her pleasure at their fragrance, a pleasure which he caught from her lips, and then fancied to be his own.”

Wordsworth’s friend and fellow poet, Robert Southey, noted 20 years later that once, in youth, the poet’s fifth sense had briefly returned: “Wordsworth has no sense of smell. Once, and only once in his life, the dormant power awakened; it was by a bed of stocks in full bloom, at a house he inhabited in Dorsetshire, some five-and-twenty years ago; and he says it was like a vision of Paradise to him; but it lasted only a few minutes, and the faculty has continued torpid from that time.

“The fact is remarkable in itself, and would be worthy of notice, even if it did not relate to a man of whom posterity will desire to know all that can be remembered. He has often expressed to me his regret for this privation. I, on the contrary, possess the sense in such acuteness, that I can remember an odour and call up the ghost of one that is departed.”

The friendship between Southey, passionate and driven by the sensual pleasures of taste and smell, and Wordsworth, enclosed in his sensory vacuum, struck me with a profound melancholy. The notion that Wordsworth was just once able to perceive the powerful floral scent of stock and lose it again seemed inordinately cruel.

On The Scent: Unlocking The Mysteries Of Smell and how its loss can change your world is published on Thursday 23 June in hardback by Elliott & Thompson.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe