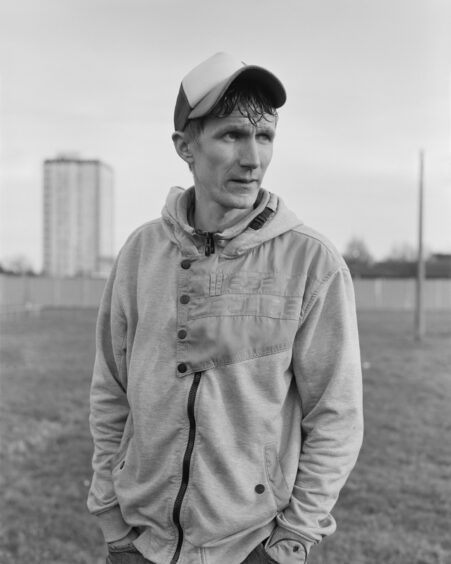

Walking through Muirhouse on a cold, wet afternoon, Paul Duke points to the places of his childhood through the smir… or at least to where the landmarks of his youth once stood.

Since moving away in the mid-1980s, the North Edinburgh community Duke once called home has undergone the kind of rapid urban regeneration that leaves once familiar streets unrecognisable, with his first home and high school just two of the familiar buildings now demolished to make way for new, modern housing and facilities.

“Whenever I came home to visit, I was really aware of the changes in the area,” explained the 57-year-old photographer, standing outside his former home, now a state-of-the-art high school. “It was slow and then really very quick.

“At the time I was living here, I didn’t know I was living in an area of hardship because it was all I knew. It was only when I left Edinburgh and started to reflect on my own past that I really became conscious of Muirhouse and what I grew up with.”

Established as a new housing estate in the 1950s, within just a few decades Muirhouse was considered one of the most deprived areas of the city, particularly from the 1980s when crime, high unemployment and drug addiction moved into the tower blocks. Anti-social behaviour made life difficult for residents, and crumbling infrastructure led to a sense of the community being left behind.

Reflecting on his childhood, Duke, who moved away from the capital to study at Royal College of Art in London, admits times were hard, but despite the social difficulties, Muirhouse was always home.

“It was a really happy time in many ways, quite idyllic, because I had a lot of friends,” explained the dad of three. “I loved growing up here. I had a great education and absolutely fantastic teachers. But, yes, it was also difficult.

“My mum brought up two boys on her own and it was hard for her. You want the very best for your children and she struggled to do that. Things were getting progressively worse in the 1980s, and that was a major concern for her. The area was getting more run down and she could see the future.

“It was a really strong community, but places start to get rundown, there’s lack of investment to maintain the fabric of the area, and people start to lose hope. It’s a vicious circle and it’s really hard to break that cycle of poverty.”

It was only after Duke left the area that things began to change. The Pennywell and Muirhouse Regeneration Project, which began in the 1990s, saw previously neglected social housing replaced with affordable, quality homes, as well as community facilities, slowly but surely beginning the transformation that has led to the area now being considered a prime example of successful social regeneration.

Lesley Hinds, who was the local councillor for North Edinburgh communities, including Muirhouse, for 33 years, says the first step was establishing the Muirhouse Housing Association, which worked tirelessly to demolish or refurbish housing that had become unliveable.

“I remember going leafletting in the area for the first time and I was really quick shocked,” explained Hinds, who has lived with her family in neighbouring Drylaw for more than 40 years. “The condition of the housing was appalling, there was poverty, high unemployment, drug issues, and people just didn’t want to move into the area.

“People often don’t believe me when I tell them this, but we couldn’t actually get any developers to come and build private housing in Muirhouse because the area had such a bad reputation. So, we subsided the first private houses built through the Housing Association.

“From there, we refurbished council housing and eventually more developers came on board. Next came a new community centre and a purpose built park because, while it’s all well and good building better housing, but you need to have facilities within the community, too. That was 20-odd years ago now, and it has stood the test of time.”

She added: “Areas like Muirhouse and others throughout Edinburgh were, frankly, neglected – and there wasn’t much drive or interest in doing anything to change that. It was really the community that pushed for better housing, redevelopment and improved facilities. The community spirit has always been at the heart of everything.”

With a strong urge to reconnect with his roots after the passing of his mum, Duke returned to Muirhouse in 2015 to begin work on a new photographic series, and it was this sense of community that turned a personal project into an examination of inequality and poverty, social flux and, ultimately, “human resilience and strength of character”.

Now on display at the City Art Centre, No Ruined Stone shows how the fabric of the Muirhouse Duke once knew has changed, but the warmth and pride of the people has remained the same.

“Initially, it was about exploring my past and trying to find out what community meant here,” explained Duke. “Then suddenly it became all about the people – and that’s when it became interesting. I realised I could make something that was valuable for Muirhouse and the city of Edinburgh as a historical document.

“A hardnosed documentary photographer would go into an area and it would all be about looking at the nitty gritty condition. Whereas my project is much more about the narrative. I’ve tried to find a narrative for the people, so it’s about the buildings, portraits, and getting a sense of time.”

Featuring 38 large-scale black and white photographs, shot on a 5×4 large format camera, the exhibition has been described as “high on humanity” by fellow former Muirhouse resident author Irvine Welsh (who famously set the Trainspotting “Worst Toilet in the World” scene in Muirhouse Shopping Centre), and Duke believes the series works as a bridge between the past and future.

He continued: “There were times when I thought, ‘What am I doing here?’ It would be a cold winter’s day, I wasn’t getting anything, wasn’t seeing anything, and started to get despondent. But once I started meeting people and hearing their stories, I realised I needed to keep going because it was really important. It became less about me and more about other people, and I loved that transition point.

“When I first came back, the area still resembled my past. Now, it resembles the next stage.

“When I was working here, the people were kind and generous, and they gave me that kind of sense that I was ‘from here’ and part of me still belonged. I found that really touching and humbling.

“A lot of people here feel that they have been misrepresented for so long and that really took over my project. It sounds like a bit of a grand term, but I felt almost duty bound to get this right and represent the community as best I could. They deserve it.”

No Ruined Stone is on display at City Art Centre now until February 19

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM