After Victory in Europe, war raged on in the Far East. While celebrations took place at home after the defeat of Nazi Germany, thousands of troops continued to fight in the sweaty, malaria-ridden climes on the other side of the world in the brutal fight with Japan.

It’s a period of the war often overlooked, until the atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, leading to the Japanese surrendering on August 15, 1945, officially bringing the Second World War to an end.

The Far East campaign had begun on December 7, 1941, with the attack on Pearl Harbour. Hong Kong was attacked the following day and, over the next few weeks, the British retreated to Singapore, where they surrendered at a cost of 9,000 men killed or injured. A further 130,000 were captured and made prisoners of war.

The fightback began in 1944 with the 14th Army – believed to be the largest ever all-volunteer army with 2.5 million men in their ranks, mostly made up of units from India and East and West Africa, as well as Britain – and the bid to recapture Burma was one of the longest fought by the British during the war.

Saturday marks the 75th anniversary of Victory over Japan Day, better known as VJ Day, and despite restrictions put in place due to lockdown, there will be a series of events to mark the date.

The Prince of Wales will lead a two-minute national silence at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire, while the Duke of Edinburgh will contribute to an event at Horse Guards Parade in London later in the evening.

Closer to home, services charities PoppyScotland and Legion Scotland, in partnership with the Scottish Government, will host on their social media channels a virtual service of remembrance at 10.35am on Saturday, followed by a virtual concert at midday. On Monday, a live lesson for schools will ensure younger generations learn about the significance of VJ Day.

Legion Scotland chief executive Dr Claire Armstrong said: “This campaign saw some of the fiercest fighting of the Second World War and in some of the harshest conditions. While Europe celebrated the defeat of Nazi Germany in May 1945, hundreds of thousands of personnel from across the Commonwealth were still engaged in the brutal fight against Imperial Japan.

“We will highlight the incredible service and sacrifice made by those who fought in the Far East campaign and unite the nation in remembrance of the generation who gave so much.”

Here, we speak to three Scots who were in the Far East during the conflict.

I don’t remember a thing after being hit

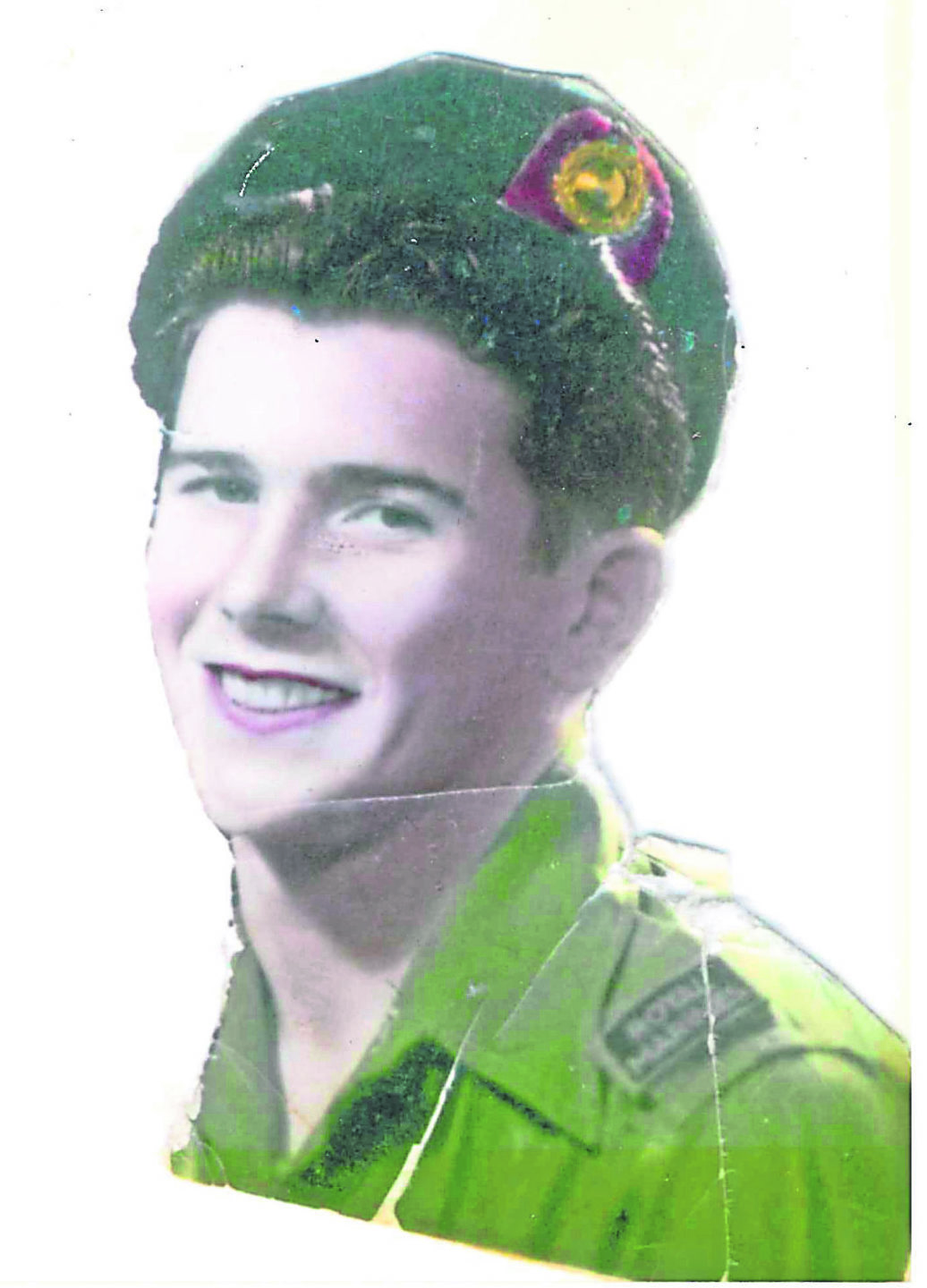

Govan teenager Frank Coyle was sent to the Far East after his conscription in 1944.

He was just 18 when he arrived in Ceylon, present-day Sri Lanka. He spent some time in the jungle, which he describes as “terrible”, before being sent to Singapore, Saigon, Bangkok and back to Singapore.

Frank was part of the 42 Commando Royal Marines, which were moved around to clear Japanese from the areas.

In Bangkok, Frank recalls releasing two prisoner of war camps, one Dutch, the other Australian. “The prisoners were skeletal,” said Frank, who turns 94 later this month.

“Their reaction was confusion – they weren’t sure what was happening to them. It was tragic seeing people coming out of POW camps, awful to witness as they could hardly walk. The Australians looked worse off.”

While in Bangkok he was hit by a sniper. “I don’t remember anything after I was hit,” he continued. “The pain felt like whiplash and then I fell unconscious. When I woke up I was in an Army tent, where I stayed for three days.”

Frank was there when the Japanese surrendered in Malaysia. He recalls going into the port in a fleet to take in the surrender, which took place on HMS Nelson. Just before Frank was called up he had met Helen at the dancing. They married in 1948 and were together for 58 years, before Helen passed away 14 years ago.

On Thursday Frank moved into the Erskine Home as its newest resident, still with a zest for life.

A signal came in that I personally deciphered, which told us the Japanese had surrendered. It felt marvellous

As part of the RAF team cracking codes and ciphers, sergeant Whitson Johnson was used to handling top-secret material.

But it was a particular thrill to decipher the signal that arrived on August 15, 1945.

“I was regularly dealing with top-secret information, things I still can’t talk about. But on this day a signal came in that I personally deciphered, which told us the Japanese had surrendered,” recalled 96-year-old Whitson from Portobello in Edinburgh.

“It felt marvellous and it was a big relief, especially in Burma where it wasn’t a good climate. We just wanted to get home.”

It was December 15, 1946, before he was back on British soil.

He’d joined the RAF in November 1942, aged 18. He wanted to be a pilot and was accepted as a PNB (pilot, navigator, bomb-aimer), training in Manchester and Derby.

But the group was told there had been greater numbers than anticipated and the RAF disbanded the courses. They were sent home on leave and told they would be called when required.

“I was called to London and asked to do some tests, and then they asked if I wanted to train as a codes and ciphers person,” Whitson said. “I was sent on a three-month course at Oxford University. After passing the course, I had to sign the official secrets act. I was made a sergeant and sent to the Far East.”

Whitson was posted to a supply wing, providing troops for the 14th Army, doing so by secret code so the Japanese wouldn’t discover the plans and movements. He was later moved to a converted Japanese air strip near Rangoon – his location when the atom bomb was dropped.

On his return home, Whitson enjoyed a “marvellous” Christmas with friends and family, and returned to his job with Unilever in Edinburgh.

He married Rita and has three children, nine grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

“August 15 is a date I will never forget,” he said. “Wars are a terrible thing. What is the point of it all? We just end up back at square one.”

There was a rumble and an RAF plane dropped leaflets on us…the war was over

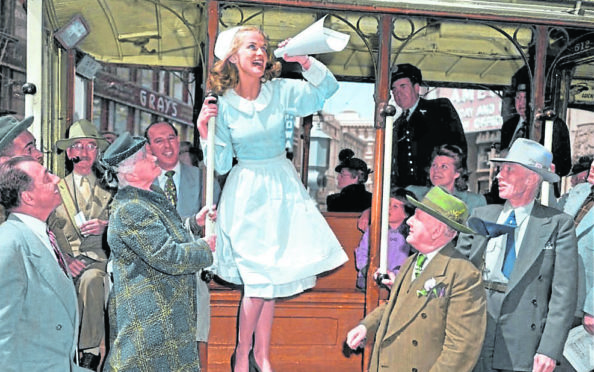

Jenny Martin spent the first three years of her life in a POW camp in Singapore with her mum, Daphne.

One of her earliest memories is of British aircraft flying overhead, alerting them the war was finally over.

“I had only just turned three,” recalled Jenny, from Edinburgh. “There was a rumbling in the distance and a plane with RAF markings flew over. The women said, ‘Thank God, thank God’. Pieces of paper with a message dropped out. ‘The war is over, Japan has surrendered, we will come for you shortly. When you are freed, don’t eat too much.’

“A few days later, trucks arrived and we were taken to a hotel to be looked over by doctors.

“It wasn’t long after my father came to see us. I remember not being sure what I thought of this strange man hugging my mother, but we soon got to know each other.”

James Davidson had moved to Singapore to take charge of a rubber plantation. Daphne worked for the Colonial Secretariat, and they married in 1934.

“My mum was destroying files her work didn’t want the enemy to see when the Japanese marched down the peninsula on February 15, 1942. She was four months pregnant. Allied civilians were told to gather in the middle of town with one suitcase, which she’d packed nappies in.”

The women were taken to Changi Prison. Daphne gave birth on July 31 and was allowed to spend two weeks in hospital before returning to confinement. James, who was eventually put to work on the Burma railway, was granted one visit when Jenny was 10 months old.

“He’d made a rattle from an old tin can and some pebbles, with a piece of wood he’d cut for the handle. It was too heavy for any baby to rattle, but it was all he had and he must have felt he needed to take a present for his new child.”

Jenny and her mum were moved to another camp when she was two, where they remained until the liberation. The family was put on the first boat out of Singapore to Liverpool.

When Jenny was 10, her parents decided she needed a Scottish education, and she came here to attend a boarding school. Sadly her father died when Jenny was 16.

It was only in her mother’s later years that Jenny learned more about what had happened in Singapore.

“I wasn’t interested when I was younger – it was my embarrassing secret,” she admitted. “But my mother was asked to speak at the Women’s Institute and was nervous, so I told her to write it all down.

“I sat in on the talk and listened, and I still have those notes today.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe