In 1949 a Scottish woman climbed a mountain that changed her life. When he put herself in her boots, Mark Cousins immediately understood, because it changed his life, too.

It’s almost a year to the day since the film-maker, movie historian and artist climbed the Grindelwald Glacier in Switzerland, following in the footsteps of artist Wilhelmina Barns-Graham.

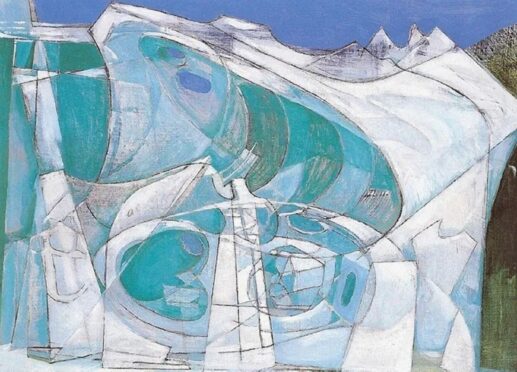

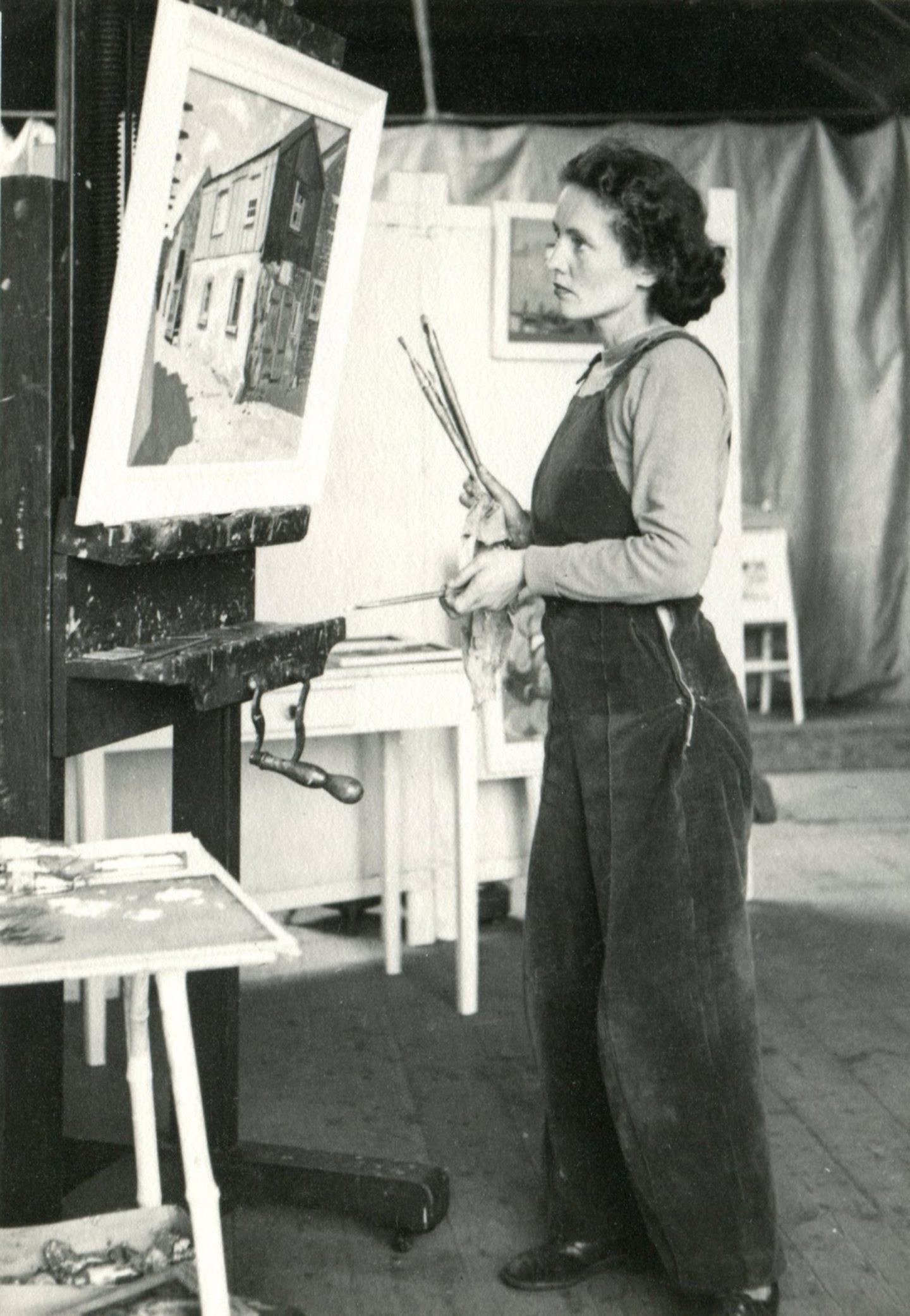

The painter, known as Willie, who died in 2004 at 91, was so moved by her ascent seven decades ago that it inspired an acclaimed series of paintings. As he followed her footsteps into the icy terrain, Cousins, who embarked on the climb despite a paralysing case of vertigo, also enjoyed an epiphany.

“Strangely, unexpectedly, I kind of had a life-changing event for a different reason,” said Cousins. “Willie’s was mostly artistic, mine was pure fear.

“Glaciers are amazing. They are transparent, it’s like standing on blue glass and it feels aquatic, it feels like you are looking at a sleeping whale because they are giant, but they’re also mobile. The light is different. It isn’t coming from the sky, it feels as if it’s bouncing up from your feet. It’s a fascinating experience.

“But it was also utterly terrifying. I was shaking, almost crying, because I have terrible vertigo. We were walking on a ledge not much wider than your feet and I was carrying tripods and things, so it was really scary for me. Walking in her footsteps, I felt something I will never forget.”

Cousins has been a fan of Barns-Graham’s work since the 1980s and has created an immersive installation in tribute to her, which opens at Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket in November.

Like A Huge Scotland will see Cousins cast a forensic eye on her glacier paintings, enlarging details to 10,000 times their original size to reveal their almost molecular structure, alongside footage of the glacier filmed on Cousins’ recent trip and a film he’s compiled about Barns-Graham and her ascent. It is something new for the polymathic Cousins.

“The film-maker in me knew that if we really wanted to understand why that climb to the glacier was so important to her, I had to do it myself,” he said. “I’ve climbed most of the Munros in Scotland, but I did not know there would be such a sheer drop and that’s what was so scary.”

But it taught him so much about the work of the artist.

“She responded to these vistas, these locations, with her whole body, with her whole nervous system almost. You just feel your heart beating fast.

“She had major breathing problems all her life so we can imagine her wheezing, and it was appropriate that I had a very physical reaction as well. It was almost a tribute to her.

“She was quite religious and she went on pilgrimages and this felt like a pilgrimage, because myself and my producers, we all adore her work and none of us knew her, but we feel really close to her, so it was like doing a pilgrimage for Willie.”

Cousins admits he’s been a fan of St Andrews-born Barns-Graham since his teens. “I don’t think I ever met her but I’ve been in Scotland since 1983 and moved in similar circles, so we were probably at some gallery opening, drinking warm Pinot Grigio together at some point,” he said with a laugh.

“I’ve been a fan for a long, long time, so to have the opportunity to do something serious about her imagination, her experiences and what made her a great artist is a real treat for me.

“I knew there was something special about her, the way she looked at the world. She would go to really beautiful places like Venice and say, ‘Nothing to paint here,’ or she would go to the Alps and not paint the Alps at all. Or she would go to Orkney with all those fantastic landscapes and what would she paint? Just the rocks at her feet.

“She looked at the world in a unique way and I wanted to capture that and get inside her head.

“Instead of doing a straight film, I thought if I did a gallery piece with four screens and eight channels of sound, then I could really put the audience inside her imagination and try and give a sense of how uniquely this woman thought and felt and encountered nature.”

Cousins not only climbed the same glacier, but spent months sifting through Barns-Graham’s old notebooks and analysing her paintings.

From their strong work ethic to a background in maths, he says they share some common traits, perhaps one of the reasons he finds her works so electrifying – and leapt at the opportunity to shine the spotlight on one of his favourite artists.

“It’s hard to believe but it started with a tweet,” he said. “I was up in St Andrews, looking at where she lived and I tweeted about it. The Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust noticed my tweet and invited me to see more of her work and I was just totally besotted, almost infected by her stuff.

“Then the trust and I talked and I said I’d like to make a film about Willie, her imagination, her experiences, this particular day on the glacier, and so it started.

“That’s the power of social media. Because I don’t live in London, or New York or Los Angeles, it has been a very good way for me making creative connections with many other people.”

The journey from then to now, Cousins said, has been a real eye-opener in many ways.

“The big difference was she climbed in 1949 and we climbed in 2021, so the glacier was huge when she climbed and it’s almost gone now because of global warming,” Cousins said. “So we had to walk about a mile further up the Alps than she did.

“It made me feel sad and alarmed. It was certainly a very melancholic experience. The woman who was leading us is only in her 30s and she remembers it being much bigger and much closer to the town. Even within her lifetime it has shrunk a lot.

“Edinburgh University has a lot of real experts in glaciology and we’ve been talking to them and they are shocked at the retreat of the glaciers, so there’s a real sense of despair when you see that these things are gone.

“You know occasionally you will see a dead whale or a dead dolphin on a beach in Scotland, it feels like that, there’s a sort of elegy for the loss of it. The climate deniers? Go and see the glaciers and you will no longer deny it.”

Like A Huge Scotland, Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket, from November 5

Willie has come alive again, a vibrant, 21st Century artist

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, who was born in St Andrews in 1912, would become one of the foremost painters working in St Ives – a hub of artistic inspiration – after moving there in 1940.

Her paintings, alongside those of her contemporaries that comprise the St Ives School, are viewed as central to British Modernism.

Film-maker Mark Cousins believes Barns-Graham, who died in 2004, was under-recognised her whole life, but is more relevant now than she’s ever been.

“These pictures of glaciers are extra resonant,” he said. “They are great works in themselves. David Bowie had one, for example.

“But they speak more loudly and more beautifully now. They’re more poignant than ever because the thing that inspired her is almost gone.”

He added: “The installation will appeal to many audiences. The audiences who go to see art, people who are interested in feminism, or ageing, and people who are interested in climate change.

“Also, Willie had synaesthesia, a condition that means when you hear a letter, you see a number. She was neurodiverse and we’re talking more about neurodiversity these days.

“These unusual sensory connections explain why she was so prolific and why her use of colour is particularly brilliant.

“The fact that she brings together all these themes means that the 21st Century version of Willie is very vibrant, very current.

“She has come alive again as a result of her representing so many themes that we are interested in today.

“She was one of the great Scottish colourists of all time, challenging a lot of stereotypes about artists, and women artists in particular.

“There was a particular awful cliche that women artists paint landscapes or families or domestic scenes, meanwhile here’s Willie painting these incredibly precise, mathematical grid-like pictures.

“Bravo to her for doing something so distinctive.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © Guenter Fischer/imageBROKER/Shut

© Guenter Fischer/imageBROKER/Shut © Anthony Harvey/Shutterstock

© Anthony Harvey/Shutterstock