It is the most popular franchise in movie history, and gave generations of children their first sense of cinematic awe.

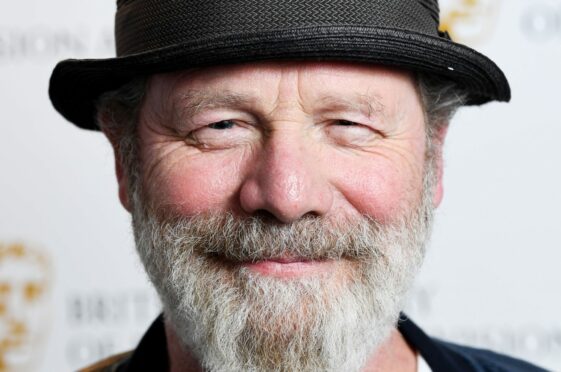

But influential filmmaker Peter Mullan says the success of the Star Wars franchise has distorted the movie industry.

The decorated writer, actor and director says the galaxy-hopping sci-fi series created by George Lucas, which has spanned six decades since Han Solo, Luke Skywalker, Princess Leia and Darth Vader first appeared in 1977, is the movie industry’s version of the “Death Star”, the planet-destroying Imperial base featured in the movies, because it is killing the chances of low-budget projects being funded.

Mullan said: “I was 17 when it came out, and it was hip at the time to go retro but what we didn’t realise was that it was going to take over all cinema, and all films that were ever going to get money to be made were going to have to kiss the glove of Star Wars and the Lucas empire.

“Now cinema is completely in the hands of the franchises and the Marvels and the DCs. Cinema has always been a young person’s medium, always designed for 12 to 25-year-olds, but what’s changed in the last 10 years is that it has become exclusively more for the 12 to 17-year-olds.

“And with that exclusivity they won’t give you the money to make any grown-up cinema because it doesn’t make them the bucks they want to make back. The reality is that now it’s really hard to make anything remotely adult, non-franchise, non-superhero. It’s hard even to get a reasonable budget.”

Mullan may be best known for roles in acclaimed TV series on both sides of the Atlantic like Mum and Ozark but has spent much of his career working in front of or behind the camera on grittier independent movies. He won acclaim as the tragic lead in Ken Loach’s drama My Name Is Joe in 1998, for just one example, and the movies he has directed include The Magdalene Sisters, an excoriating indictment of the Catholic Church abuse scandal in Ireland, and Neds, an exploration of gang culture in Glasgow.

But he has also featured in franchise projects such as the Harry Potter movies and will appear in the Amazon Prime series based on JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of The Rings later this year.

He said: “If you want to work in this business, there’s no getting away from it because that’s where the work is but like any actor you’d rather be doing something that wasn’t just that.

“I’ve nothing against franchises per se, I just don’t want them ruling the roost and at the moment they do. I’ve also got an issue with a lot of their political premise, which is ‘don’t worry – we’ll tell you who the bad guy is’. To be spoon-fed that as a 12-year-old, when you’re actually at your strongest watching films, is rubbish.”

Mullan, 63, spoke to The Sunday Post days before an adaptation of Orphans, the award-winning movie he wrote and directed in 1998, opens as a stage musical.

Originally starring Douglas Henshall, Rosemarie Stevenson and Gary Lewis, the dark comedy tells the story of a working-class Glasgow family processing their grief in the wake of their mother’s death.

More than two decades after it won a slew of awards around the European film festival circuit, it’s being given an unexpected second life on stage with the National Theatre of Scotland.

“The idea for Orphans as a musical would never have crossed my mind,” said Mullan, who earned his own chops on stage with legendary Scottish theatre companies 7:84 and Wildcat.

Mullan had two stipulations: that the team behind the project made it “as theatrical as possible” and that they avoided sentimentality.

He said: “This was not to be a pity-fest for a group of people who have lost their mammy because the whole point of the film is that all of us at one point will lose our mammies and daddies and loved ones.

“It’s not an excuse to go out and wreak havoc on your city just because you’re grieving. I couldn’t cope with anything that sentimentalised it.”

Robert Florence, Louise McCarthy and Paul McCole are among the cast of the theatre adaptation, which began its run this weekend at the Beacon Arts Centre in Greenock, before touring Scotland.

It also features music penned by Emmy award-winning musicians Roddy Hart and Tommy Reilly. Mullan said: “It’s far more accessible than I thought it would be. It’s incredibly funny. The film was uncomfortably funny, but the stage show is very much a big-hearted thing.”

Everyone needs to create, draw, write, sing karaoke, whatever

Peter Mullan wrote Orphans in the late 1990s in response to the grief he suffered over the sudden unexpected death of his mother, Patricia, an auxiliary nurse and mother of eight, when he was 34.

He said: “All the characters in it are facets of different things I felt when my mum died. They each represent a different part of what I felt: anger, self-pity, a sense of loyalty and duty, and feeling at the mercy of everybody else to make your metaphorical wheelchair function. They were all representations of different aspects of how I felt at the time.”

Mullan believes writing the film helped him process the trauma of loss.

He said: “Everybody at some stage in their life should act, draw, write, sing or whatever it is. Any creative process will help you in ways that no other form of therapy will.

“It is so vital to every human being and if life has taught me anything it’s that the creative process is at the core of one’s wellbeing and it doesn’t matter if that’s singing karaoke.

“It’s not a cure-all, but one absolutely must use it, because it is there, and it just gives you enough of a distance from the pain to make it manageable, to help you cope with it.

“When I had my first breakdown at 21, two years afterwards I was in a play where a guy had a breakdown. I was able to show it, and get a round of applause for it, as opposed to being hospitalised for it.”

Orphans opens on Thursday at the SEC Armadillo, Glasgow, before touring to Edinburgh’s King’s Theatre and Eden Court, Inverness until April 30

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © PA Photo/BBC/Big Talk Productions/Mark Johnson

© PA Photo/BBC/Big Talk Productions/Mark Johnson