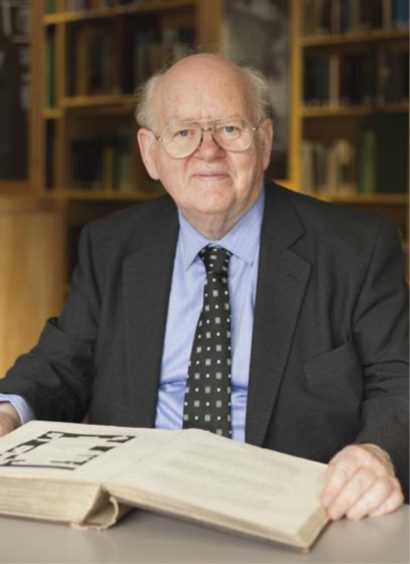

In a collection of tens of thousands of images, John R Hume has preserved industrial Scotland long after the clanging of tools fell silent and buildings were torn down or left to crumble.

The photographer, historian and author has, over the course of six decades, tirelessly documented the shipyards, mills and steelworks that have faded from the country’s landscape, leaving only memories.

The images are the centrepiece of a new book, A Life of Industry, written alongside author Daniel Gray.

It tells not only the story of works in their last throes throughout the 1960s, 70s and 80s, but also the tale of Hume’s fascination with documenting industry – according to him “fundamentally one of the most human things that there is… the interaction between people and the physical world.”

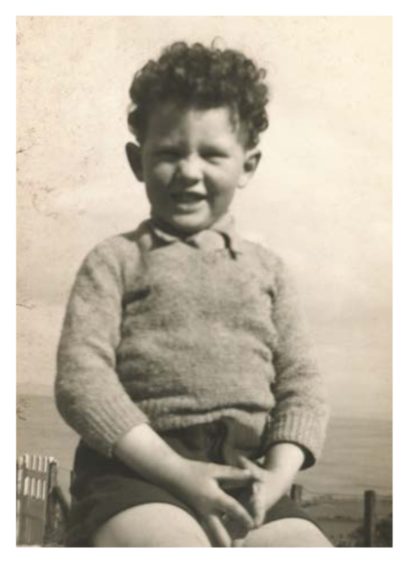

Growing up in Cathcart, Hume started to become fascinated by his surroundings at an early age. He took in the sights and sounds of his locale, hoping that there would be a way to maintain the memories of what he was seeing around him.

“When I started school, I had to walk about a quarter of a mile and I became interested in what I could see on my way there,” the 83-year-old recalled. “There was the river, factories, tenements, shops. It suddenly came to me that I hoped there’d be records of things somewhere, heaven perhaps, of all the things I was seeing and enjoying.”

Photographs proved to be the answer, and Hume would pick up his father’s old box camera aged nine. He was enthralled by the ships launched on the Clyde, and the tram and railway lines that shrunk his world, allowing him to travel further afield.

“I took as many photographs as I could afford to take,” he said. “It was expensive, not only the film itself, but getting it processed in the local chemists and having prints made.

“It was a fascinating, delightful thing to do but you had to be very careful what you took – you had to see where the sun was, and couldn’t photograph things that were moving!”

A child’s wonder became a life’s work, and Hume would spend decades producing an exhaustive and objective record, capturing industries and ways of life before they disappeared for good.

Looking deeper into each image reveals a poignant glimpse into the lives of the people intertwined with the bricks and mortar.

“The thing about being the kind of photographer I was, it used to be very looked down on because it wasn’t art,” Hume said. “I was there to record. If I came across a building then I would get it from one angle, another, from the front, the back, in such a way that if you looked at them, you could imagine the building as it existed in three dimensions.

“Fortunately, I was very lucky that many photographs I took also included people, cars, things that make them much more meaningful to people today.”

From workers giving a thumbs-up or a wave to camera, to strangers passing by, children playing or vehicles on the streets, the communities linked to industry shone through.

Hume said: “A lot of people nowadays talk about jobs, factories just as places to work but they’re far more than that and always were. In the days when I was growing up, a factory wasn’t just a place where you made things. It was a social place.

“I spent a summer at North British Locomotive Company in Polmadie attached to one of the smithies. It was so nice to interact with people, they showed me how to do things like make tea over a blacksmith’s fire.

“I remember going to a factory in Paisley where they made powdered soup, and finding out how important the social element was for women. They sat round a table, removing meat from chicken carcasses, they didn’t need to look, they just chatted away about their lives. It was just like a teashop.”

This brought home to Hume the great sense of loss linked with the decline of industry. For every plant torn down or tenement block razed for the path of a motorway was a community whose lives would change forever.

“If you close down a factory or anything like that, it takes a big lump of social life, friendships, everything that really matters to you,” Hume said.

“That’s why I’m so much against the modern notion of it all being mechanical. I’m also very against the idea of call centres, having people sitting behind a desk not talking to each other because they’re so busy being told what to do by their bosses.”

Hume’s travels took him around the country, taking photographs of the varied meanings of the word ‘industry’ around the country.

The collection doesn’t just include the warehouses, chimneys and cranes of the cities and towns of the central belt, but also the agriculture of the Outer Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland.

And over the years, he’s learned to not just look, but see.

“Small children see everything, but as you get older you filter out the things you don’t need to see,” he explained. “If you’re on a motorway going from A to B, all you need to see is the road and what the other traffic is doing.

“You don’t need to see your environment, but the great joy for me is using a bit more of your mind and vision to see things going on either side of you, the hills, the buildings, the trees – all the things that are there that you aren’t encouraged to look at.”

Hume, who spent many years as a university lecturer, turned his passion professional, helping to preserve and list some of the country’s most recognised iconic landmarks in roles including Chief Inspector of Historic Buildings for the former Historic Scotland.

One of those was Glasgow’s Finnieston Crane – perhaps second only to the Duke of Wellington and his traffic cone as an icon of the city.

“It’s one of my babies as you might say,” Hume said. “I’m delighted that it’s become a symbol of the city – that’s very much what I had in mind when we decided to list the Titan cranes.

“I wanted to choose things that we thought would matter to people in the future. Things like the Templeton’s Carpet Factory at Glasgow Green, which is such a spectacular object that people would want to remember.

“They’d want to remember the crane, the beautiful big stations that we’ve got. Outside Glasgow, the pithead gear at Barony Colliery, which is now a symbol for mining in Ayrshire, and one at Dysart in Fife.

“These are things that are reminders to people of things that mattered. Castles and abbeys are for the high heid yins. The kind of things I was trying to preserve are for everybody, not just the workers and bosses but the families. They’re part of our background and should remain so for our future.”

For all that the buildings photographed were functional and perhaps unglamorous, the beauty lies in the humanity behind them.

Hume hopes the book demonstrates his heartfelt affection for the landscapes he captured, what the buildings meant to people and vice versa.

He said: “I wanted to build a narrative of the environment which I loved. And it was all about love, really. A love of buildings, not just as objects, but because they are a part of life.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © HES. Reproduced courtesy of John R Hume

© HES. Reproduced courtesy of John R Hume © Daniel Gray

© Daniel Gray © HES. Reproduced courtesy of John R Hume

© HES. Reproduced courtesy of John R Hume © HES. Reproduced courtesy of John R Hume

© HES. Reproduced courtesy of John R Hume © Supplied

© Supplied © HES. Reproduced courtesy of John R Hume

© HES. Reproduced courtesy of John R Hume © Jane Barlow / PA Wire

© Jane Barlow / PA Wire