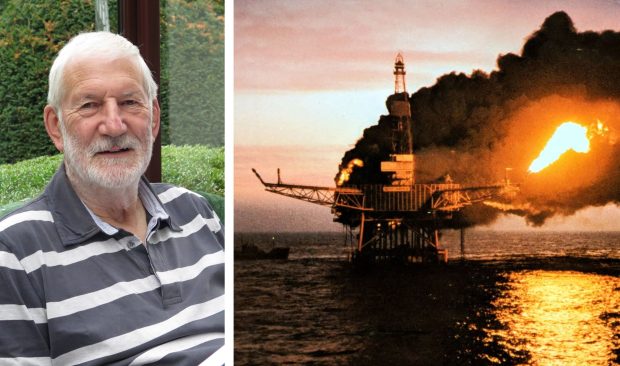

Within moments of the explosion which ripped through the gas module on Piper Alpha, captain Graham Church was scrambling to his helicopter.

The veteran pilot, on the adjacent Tharos support platform on the night of July 6, 1988, knew his S76 Sikorsky could be a lifeline to the crew of the stricken platform.

Five minutes after the initial explosion, Graham was airborne.

As they approached the Alpha, thick smoke engulfed the helipad; Graham and his colleague Ivor Griffiths could only watch helplessly as the world’s worst offshore oil platform disaster, which claimed the lives of 167 men, unfolded in the inferno beneath them.

Graham, speaking publicly for the first time about his experience, recounts the sheer frustration of being unable to help the men of Piper Alpha.

“These were people we took to and from the platform, you saw their faces in the back of the helicopter when you took them out and took them back again,” he explained.

“And then they were the faces who were gone. Faces you would never see behind you in the helicopter going home.”

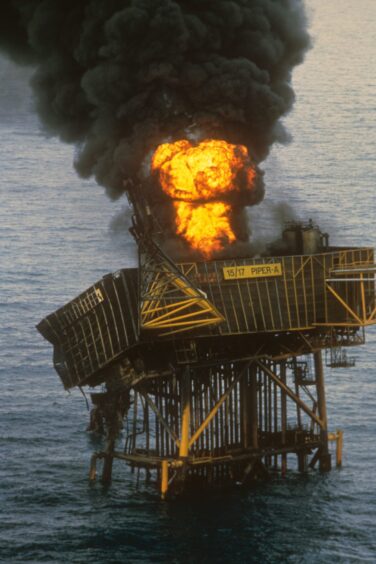

The Piper Alpha disaster

Now retired, the 76-year-old former Army pilot had been working on the North Sea for 12 years when the disaster happened. A gas explosion occurred on the platform which the later inquiry blamed on inadequate maintenance and safety procedures. The initial explosion roused Graham, on the Tharos, as he readied for an early night.

“That wasn’t unusual,” he said. “These rigs were akin to building sites. I thought perhaps a supply boat had nudged one of the legs.

“This bang felt odd though, so I got up to have a look. I could see, halfway up one of the modules of Piper Alpha, a very intense fire.

“My initial reaction was that some people aren’t going to survive that. I hoped it would be quickly put out but, boy, it just spread.”

Taking to the air with his fellow pilot, Ivor, Graham aimed for the helipad. Although their helicopter would only fit a small fraction of the crew on board at any one time, they hoped to move as many men to the Tharos as possible before the inferno took over the platform.

The wind that evening, however, was blowing in a westerly direction.

“With an easterly wind we could have tried landing but, with the westerly wind, the smoke covered the helipad, thick and black. We kept on watching to see if there was a chance to land. But there never was.

“The sheer size of it…I mean, seeing something made out of solid steel like the Piper Alpha just melting and disappearing, it was horrendous.”

The air intake valve on helicopters requires oxygen. Setting down in black smoke, even if his helicopter was lucky enough to make a landing, would likely mean not taking off again.

Desperate men, Graham later discovered, were hoping for rescue on the platform.

“I spoke to the Helicopter Landing Officer afterwards, who survived,” added Graham. “He said, ‘I think you’d have been mobbed if you had landed’. But that wasn’t our concern, we just wanted to set down.

“We didn’t even think about taking off again. We spent so long trying to spot the helideck, but it just didn’t appear. There was one fleeting look but then it was gone.

“Had we landed and had just a slightest whiff of black smoke the engines would have stalled and we definitely wouldn’t have got airborne again.”

As Piper Alpha collapsed, some men escaped by climbing or jumping into the North Sea. Graham’s helicopter wasn’t fitted with a winch, but thankfully many were picked up by a support vessel, the Silver Pit.

Graham was reduced to sending reports back to the Tharos, and taking pictures of the platform.

His fellow helicopter pilot colleagues were even more frustrated; some were left “turning and burning” – waiting with their engines running – at Dyce Airport as they waited for permission to assist in the disaster. Of the crew, 167 men were killed, leaving 61 survivors.

Return to shore

Following the events of the night, Graham returned to shore where a manager asked if he required counselling.

“I said, ‘absolutely not’,” he said. “You know, I lived through a hell of a night and I’m not sure I wanted to live through it again.

“Yet for others, that option to talk to someone about it would ultimately help very much.

“A lot of people around the disaster, not even necessarily on the Piper Alpha, had problems with PTSD. Many survivors obviously had real problems coping afterwards with what had happened.

“Perhaps for me, having been in the Army, it was different. There’s no approach that suits everyone when it comes to things like this. It’s horses for courses.

“I’m not sure about guilt surrounding what happened. It was just sheer bloody frustration.”

Graham recounted his story in a new book, Helicopters And North Sea Oil: A Story Of Service, Danger And Survival, a collection of stories from pilots operating in the burgeoning industry which sprang up in the wake of the UK oil boom in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

Originally from Hampshire and now living in Norfolk, Graham felt it was important to have a record of his experience not just as a memorial to the men who lost their lives, but their families and those who experienced the dangerous early days of oil production.

“To talk about it now, I think it was to remember not just those who died but those who survived,” he said. “I think about it like this: that night, 167 people died. That means perhaps 10 times as many were viscerally affected, like spouses, partners, children, and 10 times as many again who were colleagues.

“Then there were again the 10s of thousands of people in the industry around the world who felt the pain of that night, the pain of what happened, in the pursuit of oil.”

Safety procedures were implemented following the Cullen Inquiry which examined what went wrong on Piper Alpha. But, when looking at what could have been different that night, Graham isn’t sure there was anything that could have helped his helicopter touch down.

“We saw the deck once, fleetingly, so tried to set ourselves up for an approach but by the time we’d done that it was gone again,” he added.

“Looking back, nothing would have helped. The fire was rapid, it was all-encompassing, and all we could do was watch.

“If we’d had an easterly wind? Who knows?”

Helicopters And North Sea Oil: A Story Of Service, Danger And Survival by Peter Saxton, published by Pen & Sword, is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © PA

© PA © Colin Rennie

© Colin Rennie