When Fergus Monk’s customers come to his garage, they pull in to have their cars fixed but, by the time they pull out, they’ve been taken on a road trip, all the way down memory lane.

A visit to the mechanic’s Port Glasgow garage is no ordinary pit-stop. Not only does Monk’s yard on the quay overlooking the Firth of Clyde have one of the best views on the west coast, it’s as beautiful inside as it is out.

The 66-year-old, from Benbecula in the Outer Hebrides, has turned his garage into an art gallery featuring huge murals, each one depicting meticulously detailed scenes from a bygone age.

Now the islander is set to unveil his latest artwork, a huge rural mural in homage to the island life he left behind as a boy.

He said: “I decided I wanted the early part of my life put into a painting.

“Wherever your earliest memories are formed, I think your heart always wants to go back there. It’s where your heart is. I’ve been in Port Glasgow for 50 years and love it here but in my case that’s Benbecula.

“I think everybody has a place like that – it doesn’t matter where they go or end up. It’s about where they came from.”

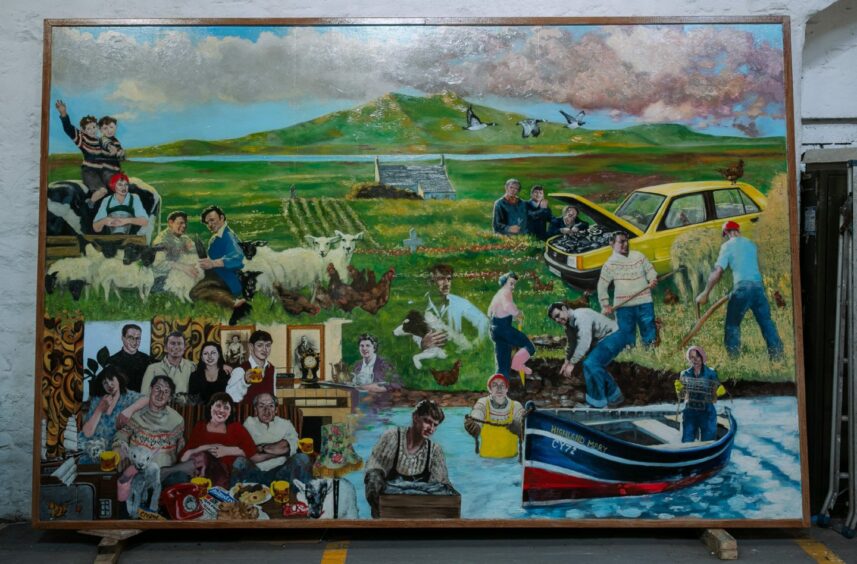

Monk commissioned Inverclyde painter Jim Strachan to depict his family’s way of life on their croft in the 1960s. He spent five months working from photographs and anecdotes of Monk’s life on the south-east tip of the island, to make the 12ft by 8ft oil painting.

“Jimmy became part of our lives,” said Monk. “We’d have our tea break and lunch break with him every day. Customers would talk to him as he painted.”

The artist, director of Greenock-based charity RIG Arts, pitched up to paint as the garage’s team of mechanics worked on customers’ cars.

Monk said: “I told Jimmy I wanted various memories from my life growing up in the islands transposed into a painting. I wanted it to be vibrant and full of colour. Every time you look at it, you see a wee story.”

The mural is bursting with character, depicting grandparents Kate and Neil, parents Donald John and Peggy and Fergus’s siblings Neilly, Mary, Marion, Colin and Iain, as well as his wife Betty. Every inch is covered with family lore.

There’s the old yellow Renault with hens living inside; Fergus’s brothers scything hay for bales; the lambs rejected by their mothers, eating biscuits in the family living room; the grave for Bessie, their beloved Border collie; the family digging peat and layering mackerel; the black-and-white photographs of his grandparents, hanging above the fireplace; row upon row of lazybeds, where potatoes were grown, fertilised by rotted seaweed; and his sister standing in Highland Mary, her grandfather’s old boat, holding an empty lobster creel.

Monk said: “Mary has an open creel and she’s laughing, because she didn’t like the killing of any animals. She set them all free. And if you look here at the newspaper headline in the coffee table it says, ‘Vegetarian discovered on island.’ There’s so much detail.”

A shattered smoking television tells another story. Monk said: “My mother Peggy got that television, it was rented from a company in Stornoway. I came home one day and the living room floor was covered in glass. My brother Neilly told me what had happened.

“He’d been sitting in the chair with my father’s 32in single-barrel, hammer-action shotgun and hadn’t realised it had a cartridge in it. He ended up blowing the television to bits. He told our mother it must just have exploded when he was in the kitchen.”

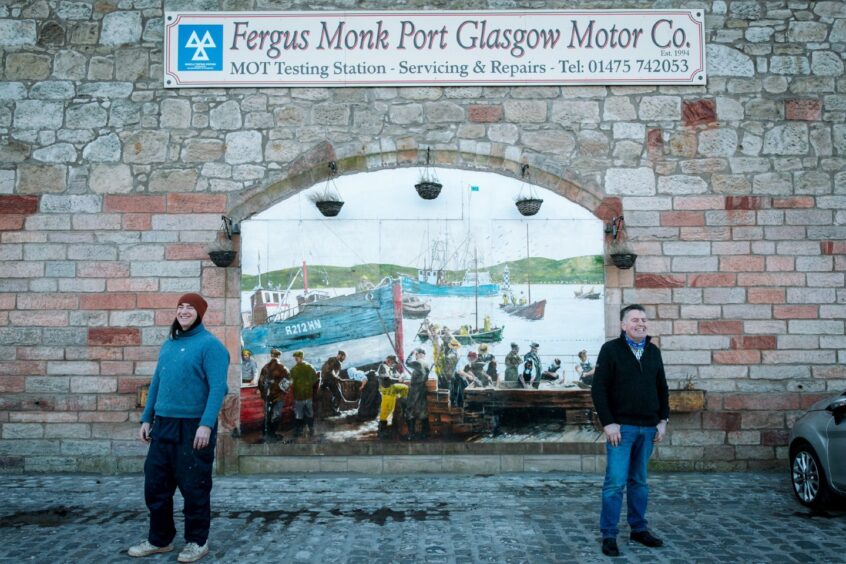

His garage is an old warehouse from the 1800s, one of several repurposed relics from the town’s industrial legacy. But this is no grease pit. It’s adorned with hanging baskets in the summer and an upright piano is wheeled out at Christmas for customers to play under a 40ft Christmas tree.

Monk and Betty have created a garden outside with tables and chairs where they take tea breaks with passers-by.

The new mural will join two older works Monk commissioned in 2016. One depicts crowds waiting for the arrival of the Waverley paddle steamer, which once docked at the nearby quay.

The other painting depicts the fisherwomen who once worked with the catch at the shore, and the shipyards in the background.

Strachan said: “They’re in a really vulnerable spot and they’ve never been touched. Maybe the paintings remind kids of their granny or their granda or something, but I think if you do a mural the right way they won’t get vandalised.

“I was effectively working in tandem with him. It worked out well. I initially had a beach scene in the painting, depicting his brothers coming back on a boat with the shopping, and he didn’t like it. So I took it away.

“Fergie would see it every day and we could make changes and perfect things as we went along.”

Strachan has made his mark elsewhere in the area. He recently completed a mural at Inverclyde Royal Hospital and previously worked with RIG Arts to produce a series of murals inside Port Glasgow train station.

The 53-year-old said: “I grew up in Thatcher’s 80s in Inverclyde and took witness to what she did to this area. But through art you can generate positive community spirit.

“If you make art in such a way that it shows integrity, then it can generate something that goes beyond a visual depiction of something. We wear our heart on our sleeves when we go into an area, and want the best for the place and its legacy.”

The murals have found an unexpected audience, with thousands coming to photograph the giant metal shipbuilder sculptures, known locally as the Skelpies.

Monk said: “I’m really happy how things have turned out with the mural.

“Everyone who is in it, who isn’t around to see it now, would love it too. It’s a way of keeping their memory alive. I’m proud of it.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley