Wimbledon was not quite the same this year. At 86, now using two sticks on his increasingly rare public appearances, King Edward IX was too frail on the final Sunday to attend and present the prizes.

Nicholas, Prince of Wales, pleasant and bespectacled, attended in his stead. Later that night their cousin Princess Elizabeth, recently widowed Duchess of Edinburgh, gave a rare TV interview, looking back on a low-key country life. Old folk still occasionally cluck: “You know, she would have made a wonderful Queen…”

Absurd? But for a desperate night or two in 1936 and at the height of the abdication crisis, serious thought was indeed given – Edward VIII being implacably determined to go – to bypassing not only the dull Albert, Duke of York, but also Henry, Duke of Gloucester and bestow the monarchy on the fourth brother – cultured and sophisticated, fluent in five languages, devastatingly handsome and, at the time, the only son of the late George V with a male heir.

But Prince George Edward Alexander Edmund, Duke of Kent, would not wear the crown – nor, as it proved, even see his 40th birthday. At five past one on the afternoon of August 25, 1942, a ponderous, deep-bellied Sunderland seaplane took off from the Cromarty Firth on a VIP mission to Iceland.

It was a soft day with patchy mist and fitful sunlight. Forty minutes later, residents around Dunbeath in Caithness heard the Shorts S.5 Sunderland Mk III rumbling overhead, voyaging inland and ominously low. And then there was an enormous bang.

The aircraft, all four engines at full throttle, helmed by two crack Australian pilots, had smashed into bog near the summit of Eagle’s Rock, somersaulted and – its tanks abrim with 2,400 gallons of fuel – exploded.

Of the 16 people on board, only one survived: Flight Sergeant Andrew Jack, rear gunner. At some distance from the other broken bodies lay George, the King’s brother, still only 39, our Queen’s lost uncle – and a figure to a striking degree erased from our history.

There has been much speculation about this Highland tragedy. That the Duke himself had been at the controls of the aircraft. That he had been drunk. That a girlfriend had been smuggled on board. Or a boyfriend. That the Duke had been flying to a Caithness stately home to pick up Rudolf Hess.

Or was at least heading for Sweden to negotiate with the Nazis. That there was a cover-up: why have all the papers, including those of the subsequent RAF Court of Inquiry, disappeared? And then the hearsay evidence, second or third-hand from witnesses long dead.

Actually, papers have not disappeared – the 87-page Court of Inquiry report was unearthed, some years ago, in the National Archives of Australia – and the Duke of Kent’s death is, arguably, the least interesting thing about him.

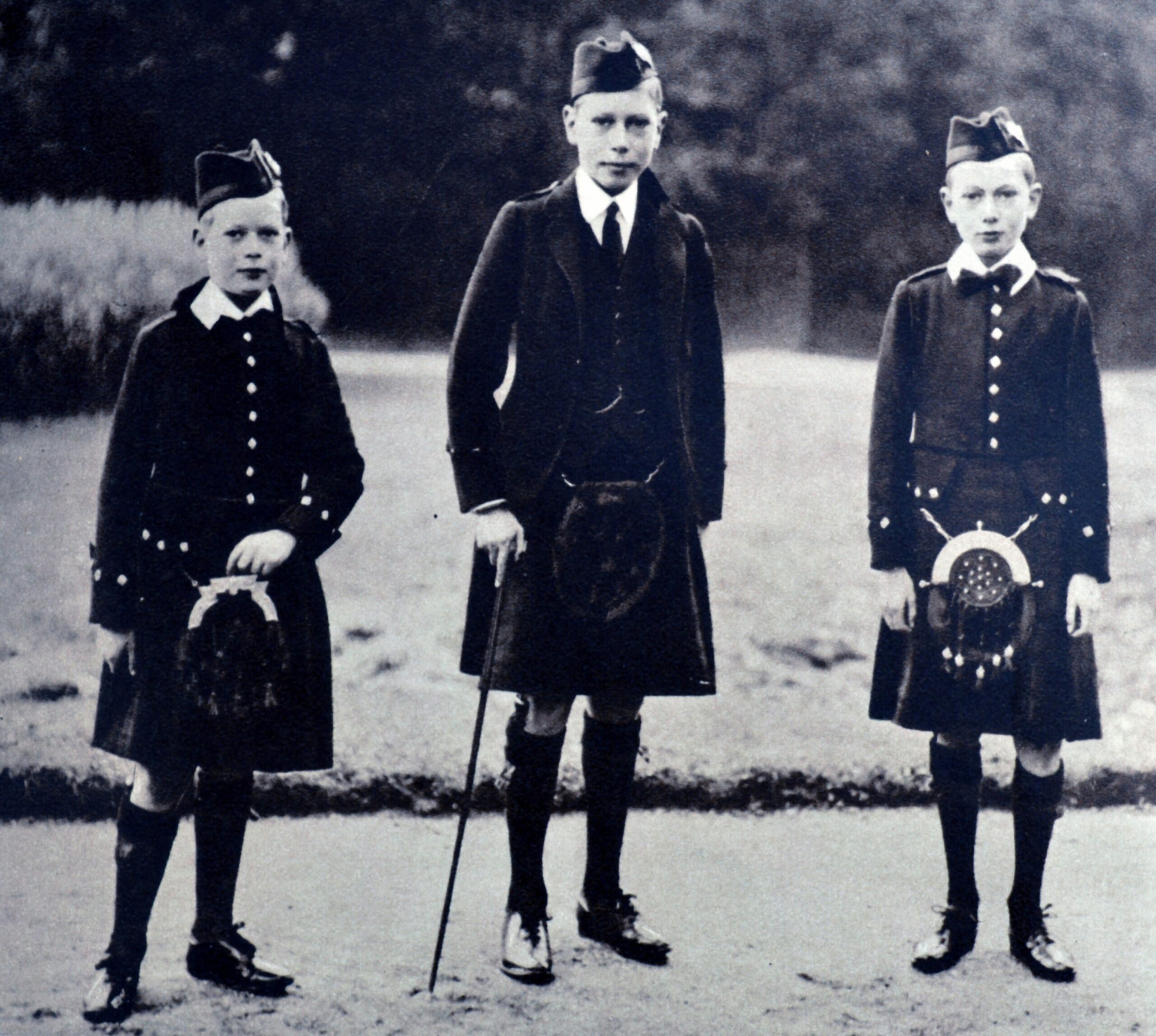

Prince George was born at York Cottage, Sandringham, on December 20, 1902, the fifth child and fourth son of the future King George V and Queen Mary. He was far enough down the pecking-order to escape the worst excesses of his father – delightful with other people’s children, George V was pretty nasty to his own – and, of all the brood, the future Duke of Kent was closest to his mother, from an early age sharing her passion for beautiful things.

He was also devoted to the family’s final baby, Prince John, born in 1905, who, almost certainly autistic, was in time entrusted to the care of an old nanny in a Sandringham cottage, safely out of the public eye. George felt his death in 1919 dreadfully.

Only the second royal prince ever to attend school, George excelled in his studies and came home, every holiday, with glowing reports. He took to the piano, and so shone as a dancer that, in 1926, in the south of France, he entered a tango competition incognito – and won.

George happily spent hours on end with his mother, discussing antiques and decoration and Renaissance art but, growing up, struggled to find a niche. His brothers loved to shoot at Sandringham; George much preferred sunbathing at the Riviera. He would tour art galleries; hammer down country lanes in fast cars; play Cole Porter on the piano.

George haunted the cinema, the theatre and the ballet, and devoured newspapers. He was far better informed than his brothers and an assured public speaker. Yet, always, there was Papa. George “probably suffered most from his father’s blistering talk and unyielding attitudes,” mused royal biographer Theo Aronson in 1984.

“His emotional, artistic and unconventional nature was something that the King would never have been able to appreciate.”

Instead, deaf to all entreaty, George was forced to attend naval colleges at Osborne and Dartmouth, followed by service in the Royal Navy.

“I’ve tried to make him see that I’m not cut out for the navy,” the prince lamented to Lady Airlie, an intimate of his mother. “But it’s no use. What can I do?” What George ended up doing was ducking as much naval duty as possible and rattling around cafe society having a great deal of sex.

“Some of the tales are undoubtedly tall but, still, so careless was the prince that on more than one occasion some lover or other had to be bundled out of the country. Randolph Churchill murmured to diplomat Robert Bruce Lockhart of still more scandal, of “letters to a young man in Paris. A large sum had to be paid for their recovery.”

The nadir was George’s fling with Alice “Kiki” Preston, known in their louche circles as “The Girl with the Silver Syringe” and who soon had the prince hooked on drugs.

At this low point he was all but arrested by his elder brother, the Prince of Wales, who kept him under lock and key, nursed him and broke the addiction.

George never delved in such dark waters again. In 1929 the King at last let him leave the Royal Navy to become the first royal to work in the Civil Service. That same year, George acquired his pilot’s licence and, doubtless happier, became much more circumspect in his private life.

In the spring of 1934 Princess Marina of Greece, his second cousin, visited London. Something clicked. Nothing was said, but in August the prince flew dramatically to Yugoslavia in his own little plane, where Marina was visiting her sister Olga – and three days later their engagement was announced.

King George and Queen Mary could not have been more delighted. Marina, too, was one of the best-dressed women of her age, sweet-natured, highly intelligent, and with a beguiling, lopsided smile. Their wedding, on November 29 at Westminster Abbey, was the first royal occasion ever to be broadcast live. He – created the Duke of Kent shortly before – was resplendent in naval uniform; she was in a silver, sheath-like dress by Molyneux.

And for a season this “dazzling pair,” as diarist Henry “Chips” Channon dubbed them, glowed at the top of society. They had three children by August 1942 and, while Marina was by no means blind to her prince’s colourful past, there was deep mutual respect.

“I am really a very bad hostess,” the Duchess once laughed to Lady Airlie, after some fabulous feast. “My husband chose the dinner and the wine – and the flowers and everything else. He enjoys doing it.”

There was one cloud on the horizon: the Prince of Wales’s mortifying entanglement with a married American woman. And, on the death of George V in January 1936, it became an emergency. Long close to his big brother, George found it ever harder to see him, and harder still without the company of Mrs Simpson.

“He is besotted on the woman,” the Duke of Kent exclaimed angrily to Stanley Baldwin, Prime Minister. “One can’t get a word of sense out of him.”

And, naturally, those closely involved were ever tight-lipped thereafter about discussions over the succession. Yet there had been desperate doubt about the Duke of York’s suitability.

Albert was painfully shy, ill-tempered, poorly educated, and cursed with a stammer. He had never in his life seen a state paper.

And as early as 1952, Dermot Morrah – writing, of all things, an authorised biography of Princess Elizabeth – spilled the beans.

“It was certainly considered at this time whether, by agreement among the royal family, the crown might be settled on the Duke of Kent – the only one of the abdicating King’s brothers who at that time had a son to become Prince of Wales and so avoid laying so heavy a future burden upon the shoulders of any woman.

“The possibility of such a course was debated by some men of state who believed that it would accord with the wishes of the royal concerned.”

And, in the National Archive some 15 years ago, author Christopher Wilson found an astonishing note in the papers of Sir Horace Wilson, then head of the Civil Service. It is but one sentence: “Suggested that Queen Mary should be appointed Queen Regent until the divorce and the Abdication should be over.”

Perhaps she scuttled further constitutional tinkering in the end. Albert, of course, did assume the throne, as King George VI. And no role befitting his gifts was ever found for the Duke of Kent.

At the wishes of the government he spent weeks in 1938 in Germany, meeting top Nazis and reporting back on their intentions: he was perfect for such a mission, but it was never repeated.

Plans to make him governor-general of Australia were shelved by the war and, after some months in naval intelligence, the Duke became an Air Commodore in the RAF, flown around on dull, morale-boosting business – until that misty afternoon at Eagle Rock.

There is no reason to doubt the Court of Inquiry’s conclusion: pilot error. The plane had turned west two miles too soon. A slow climber, the Sunderland seaplane should never have been flown overland, and not “on instruments” when visibility was so poor.

The Court of Inquiry singled out for praise Dunbeath’s GP, Dr John Robert Kennedy. In the preceding two years, he was the first medical officer on the scene of six air crashes, so commonplace locally were these prangs. Three aircraft even managed to slam into tiny St Kilda during the war.

Other conspiratorial notions can be dismissed. The alleged and maudlin tales of Andrew Jack, who died in 1978, can be discounted. Rudolf Hess, dim and crank, was a non-entity, which was precisely why Hitler had made him his deputy. After his sensational 1941 flight to Scotland, the Führer had stripped him of all his offices and given secret order that, should Hess return, he be shot on sight.

The idea that Hess was in a position to negotiate anything is absurd; talk of Highland rendezvous with the Duke of Kent laughable – by August 1942, Hess had begun a three-year stint in a secure Welsh hospital – and, by then, the war was already going wrong for Germany and America had entered the conflict.

It is strange, nevertheless, how the Duke of Kent has been swept out of mind. No statue was ever raised of him. His generous Civil List allowance died with him and Marina – who would live till 1968 – had to scrape ignominiously by, reduced to selling paintings and treasure.

No official biography of George, Duke of Kent has ever been authorised, and the Palace and indeed his family have given all approaches short thrift. Yet he had come within a whisper of the Crown and, had he lived as long as his mother did, would have reigned till 1989.

She missed him sorely. “He often used to say I looked nice,” Queen Mary once sighed. “Nobody else ever did.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Frank Scherschel/The LIFE Pictur

© Frank Scherschel/The LIFE Pictur © Universal History Archive/Shutte

© Universal History Archive/Shutte