Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee was very nearly upstaged by a flamboyant American showman and former cowboy.

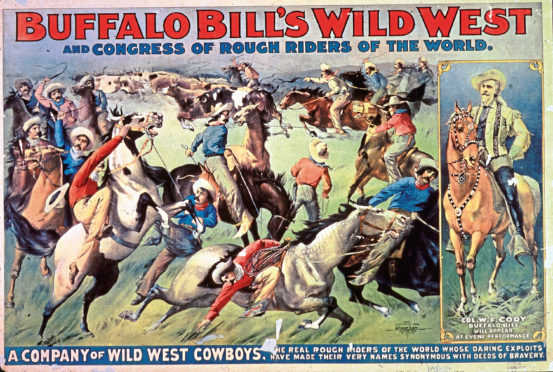

Long before the cinema had immortalised the American “Wild West” with action-packed accounts of the battles between cowboys and Indians, Buffalo Bill brought his spectacular Wild West Show to Britain for the first time in 1887 – the Queen’s Golden Jubilee year.

Colonel William F Cody – his real name – produced more than 300 open-air shows in 130 towns and cities in the UK, playing to 2.5 million people over a seven-year period.

The fascinating story of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, from its origins in Nebraska in 1882 through to Cody’s last appearance in Portsmouth, Virginia, in 1916 is told in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: The First Reality Show In Essex, by the veteran BBC journalist and historian David Dunford.

Cody was one of the all-time great showmen, as accomplished at re-enacting such events as the Battle of Little Big Horn, in which General Custer was slain, as he was at negotiating the logistical feat of recruiting hundreds of “cowboys and Indians”, taking good care of them and transporting them, along with vast amounts of kit, around the country.

A reporter from The Globe newspaper was despatched to Gravesend to meet the SS State of Nebraska as it came in to dock, carrying 176 horses, 16 buffalo, nine elk, the original Deadwood stagecoach – made famous by Doris Day in the film Calamity Jane – not to mention the cast of 200 real-life cowboys, native Americans, Mexican vaqueros, the sharp-shooter Annie Oakley and, of course, the imposing figure of Colonel William F Cody aka Buffalo Bill himself.

The reporter wrote: “The living freight on board the State of Nebraska is probably as curious and certainly as mixed as was ever sent afloat. There stood the Redskins, mute and immovable. Haughty in mien, graceful in manner, picturesque in dress, the Red Indians of the Wild West show and the Last of the Mohicans are one and the same.”

Another newspaper report of the time noted the native Americans standing in the sunshine watching as the Nebraska’s extraordinary cargo was unloaded: “Looking upon the chiefs, braves and squaws, one could not help recalling the delightful sensations of youth – the first acquaintance with the Last of the Mohicans, the Great Spirit, Firewater, Laughing Water and the Dark Huron Warrior.”

Later Buffalo Bill expressed some anxiety in his diary about the wisdom of the enterprise: “The freight I’d brought with me across the broad Atlantic was such a strange and curious one that I naturally wondered whether, after all the trouble, time and expense it had cost me, this pioneering cargo of Nebraska goods would be marketable.”

He needn’t have worried.

The inaugural show in Earl’s Court, as part of the American Exhibition, was a huge hit, drawing crowds of 28,000 on its opening day.

The show was performed against a vast scenic backdrop depicting the prairie, with mountains, rocks and trees.

It was designed to illustrate the life of the frontiersman and the North American Indian, as performed by the real protagonists, rather than actors.

The authenticity of Buffalo Bill’s show was stressed in an article in The Illustrated London News: “It is not a circus, nor indeed is it acting at all, in a theatrical sense, but an exact reproduction of daily scenes in frontier life as experienced by the very people who now form the Wild West Company,” it read.

“It comprises Indian life, cowboy life, Indian fighting, lassoing and breaking in wild horses, shooting, and feats of strength.”

Just two days after the opening of the show in London, Queen Victoria decided to see what all the fuss was about.

Her son, the Prince of Wales, had already seen the show and commended it to his mother.

She decided to attend a special hour-long “command performance” at Earl’s Court – the first time the Queen had attended a public performance since the death of Prince Albert 26 years earlier.

A special royal box was erected, with a dias at the centre on which the Queen would be seated.

Cody instructed that a rider should do a circuit of the arena bearing the American flag.

He later claimed that it was the first time since the American Declaration of Independence that a British monarch had recognised the star-spangled banner, symbolising an end to any animosity between Great Britain and America.

After the show, Cody was presented to the Queen. He described her later as “a kindly little lady, not five feet in height, but every inch the gracious Queen”.

In turn, Queen Victoria wrote in her diary: “All the different people, wild, painted Red Indians from America, on their wild bare-backed horses, of different tribes all came tearing round at full speed, shrieking and screaming, which had the weirdest effect.

“The cowboys are fine looking people, but the painted Indians, with their feathers and wild dress (very little of it) were rather alarming looking. Buffalo Bill, as he is called, is a splendid man, handsome and gentleman-like in manner.”

Five years later, on one of his return visits, Cody was summoned yet again to perform before the Queen, this time at Windsor Castle.

The stunt riding had become even more spectacular with the addition of a troop of Cossack horsemen.

Apart from all his other skills, Cody was a tireless self-promoter, making sure whichever town they were playing was fired up by posters, flyers, newspaper adverts, interviews and articles extolling the wonders of the Wild West.

Cody would despatch members of the company, in full native dress, into the town ahead of the performance to mingle with the locals and hand out flyers.

Moving the show around from town to town was a massive, mind-boggling task carried out with military precision. Eleven-acre sites had to be found on the outskirts of town, and a grandstand seating 12,000 erected.

The company numbering 800 had to be fed and housed, not to mention the scores of animals. Each venue became a fully-fledged community for the duration.

Crowds would gather just to see the show’s arrival in town, taking up three-quarters of a mile of rolling stock.

The Ilford Guardian gasped: “On Tuesday next there will arrive in Ilford the most remarkable train freight that has ever been brought here by the Great Eastern Railway Company.”

Four days before the show opened in Chelmsford, the Essex Chronicle was writing: “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West has never been to this town before and can never return. It is not a circus but consists of genuine representatives of different races and nations, associated with perfection of horsemanship and military skill.”

Cody’s own credentials as a warrior, horseman and crack shot were genuine enough. Growing up in Salt Creek, Iowa, he became the family breadwinner in his early teens, following the death of his father, working first as a cowboy, then as a wagon train messenger, liaising between westward bound freight wagons headed for California.

He graduated to the Pony Express which carried messages across the country, from New York to San Francisco, in a kind of four-legged relay.

There were numerous encounters along the way with hostile Indians. Three years into the American Civil War, aged 18, Cody joined the Union Army as an undercover scout, disguising himself as a Tennessee farm boy with a southern accent. Whoever assigned him to that job obviously spotted some of his skills.

Later, after the war was over, he found a job as a peacetime scout under the command of General Custer.

The nickname Buffalo Bill derived from a subsequent job as a supplier of meat to railway builders, which meant shooting hundreds of buffalo.

He subsequently led groups of rich adventurers on buffalo hunts, which introduced him to the educated elite of east coast society, including the writer Ned Buntline who wrote an article for the New York Weekly, with the headline “Buffalo Bill, The King of the Border Men” glorifying the 23-year-old Cody’s reputation.

A series of published adventures followed, along with a stage play, Scouts Of The Plains, in 1872 in which Cody himself appeared.

By all accounts, the play was terrible. Cody couldn’t remember his lines so he adlibbed about a recent Wild West adventure, and the public flocked to see it.

Cody’s last great real-life adventure came in 1876 when he returned to the service of General Custer, as chief scout, to help deal with the Indian uprising that culminated in the legendary Battle of Little Big Horn in which 268 soldiers lost their lives.

During the skirmish Cody was alleged to have shot and killed a Cheyenne chief named Yellow Hand at close range, although he later dismissed the story as apocryphal.

However, this did not stop him re-enacting the battle – and his own heroism – in his Wild West show.

It was only six or seven years after these savage encounters that Buffalo Bill started to employ and work alongside the very Indians, or native Americans, he had spent years trying to suppress. That alone speaks volumes for his charisma and diplomacy.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: The First Reality Show In Essex by David Dunford – www.essex100.com

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

© Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images © Stock Montage/Getty Images

© Stock Montage/Getty Images