FOR sheer longevity, no royal marriage comes close to our current monarch’s 70 years with Prince Philip.

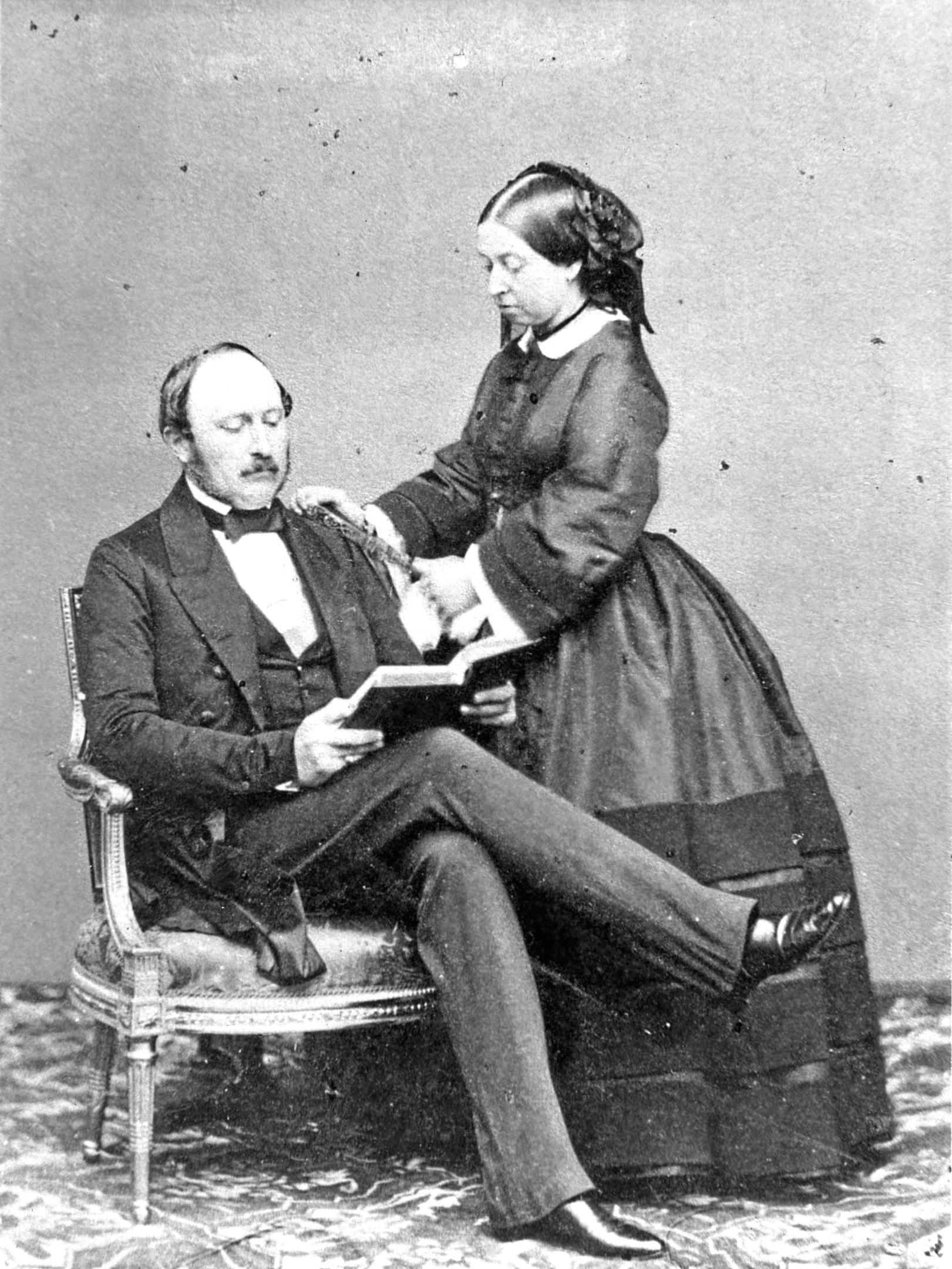

When it comes to love stories, passion, lust and thousands of pages devoted to a Queen’s spouse, however, Victoria and Albert are miles ahead!

As Queen Victoria wrote almost obsessively in her 141 journals, life was pretty meaningless when her “beautiful” Albert wasn’t around.

She wrote passionately about, well, passion, and her diary notes were shockingly intimate for her time. Their wedding night, for instance, she described as “bliss beyond belief”.

She worshipped her husband.

Some historians have even questioned whether Victoria and Albert were neglectful parents to their nine children, so wrapped up were they in each other.

When Albert died at just 42, in 1861, his widow dressed in black, locked herself away, and spent many years in grief.

She disappeared for so long, in fact, that the public began to turn against her for shunning them. She only reappeared when her advisors warned of a looming crisis if she didn’t.

It’s all the more surprising, then, that some around young Victoria didn’t fancy Albert, her first cousin from Germany, as a potential husband.

Christened Alexandrina, the future Queen Victoria described her childhood as melancholy, her adored spaniel Dash her only real company.

Her mother, the Duchess of Kent, realised the girl could be Queen one day and raised her under strict rules, known as the Kensington System, controlling every moment of her life.

It involved her education and strict daily routines, but really the idea was to make her as dependent as possible on her mother and her companion, Sir John Conroy.

The Duchess also conspired with Leopold, King of the Belgians and her brother, to pair the girl off with Prince Albert.

Victoria’s uncle, King William IV, who had no legitimate children of his own, felt Albert would not do at all, preferring Prince Alexander of the Netherlands. But the Duchess got her way, and Victoria and Albert were introduced.

To say they clicked is a gross understatement.

While the young Victoria would describe Alexander as “very plain”, Albert was “extremely handsome”, and she even wept when he left.

It was no competition!

She wrote to Leopold, thanking him for arranging the meeting and “for the prospect of great happiness”.

Albert, she wrote: “Possesses every quality that could be desired to render me perfectly happy. He is so sensible, so kind, and so good, and so amiable, too.”

He had, she said, a “pretty mouth and a beautiful figure, broad in the shoulders and a fine waist”.

All this from a lady whose name would one day become synonymous with prudery and overly strict morals! There would be plenty of Victorian prudes, but Victoria wasn’t one of them.

Both she and Albert were 17 and already fixated on one another, and though that was a bit young for the likes of Leopold or the Duchess to push things further, something else would.

The death, in the summer of 1837, of William IV saw Victoria suddenly thrust towards the throne, just as Queen Elizabeth II would be with the death of her father.

Her mother had to come and live with her at first, as social conventions meant an unmarried woman should live with her parents.

Victoria found rooms as far from her as possible for her mother to live in — she was too busy firing off letter after letter to Albert, back in Germany.

She took a great interest in his education, as Albert studied art history, law, politics and all sorts at Bonn University. When they were husband and wife, she would seek his advice on all manner of decisions.

Victoria would reign through some massive historical events, and she’d find Albert, for the short time she had with him, was the ideal companion.

They were reunited in late 1839, and within five days, she had proposed to him!

It was not the sort of thing a Queen ought to do, they said, but when love is in the air, protocol goes out the window.

Clearly impatient, they were married on February 10, 1840, in the Chapel Royal of St James’s Palace.

Victoria wore white, setting the tradition that has endured, and with flowers in her hair. The Prince was handsome and dashing in his military uniform.

The bride was led down the aisle by her uncle, the Duke of Sussex, and the couple said their vows at 1pm.

A dozen bridesmaids carried the train of her satin dress, pinned to which was a stunning sapphire brooch Albert had given her.

To this day, of course, her great-great-granddaughter, Elizabeth II continues to wear it.

It will come as no surprise that Victoria carried a posy of orange blossoms, the symbol of fertility, as she would go on to have those nine children!

A three-day honeymoon at Windsor Castle, scene of their very first meeting, seemed short, but the Queen couldn’t be away any longer.

She had enjoyed the wedding, calling it “the happiest day of my life”, and the wedding night — “the most gratifying” — but she also wanted to get back to work, her new husband at her side to advise and encourage.

She did have an Empire to run, and Victoria was always utterly focused on it. Well, when she didn’t stop to admire her beautiful husband, that is.

Although she had one child after another, Victoria hated being pregnant and childbirth, and they reckon she had severe postnatal depression, too.

Albert, however, was a family man. The children’s governess said he was always extremely patient and kind with them.

He came up with a special education plan for his eldest son, Albert, the future Edward VII, and loved to join in games, not afraid to make fun of himself to entertain his family.

Their mother, on the other hand, didn’t play games. She was far too busy with serious, grown-up things.

Ironic, then, that Albert was the one who could go off on moralising rants, much to the irritation of his wife.

They reckon Albert also played a major role in bringing something new to Britain — the Christmas tree.

If she liked his trees, Victoria hated his moralising, and when he suggested she ought to be more actively involved in governing the country, she took one of her regular tantrums.

Sometimes these got so bad and so frequent, her husband took to putting notes under her door, as it was shut tight and he was not welcome!

Albert did come in handy for more than just passion and being pleasant on the eyes though — as Victoria spent more and more time expecting, he took on many of her Governmental roles.

Annoyed at being robbed of her duties, she was also well aware that he carried them out to perfection and was clearly a talented, well-organised man.

It says a lot that this marriage, which could be such a tricky balancing act in many ways, was also rock-solid.

It takes one to know one, and Sir Robert Peel, twice Prime Minister, said Albert was: “The most extraordinary young man you will ever meet.”

Interested in the arts, science, inventions and politics, Albert also had a strong social conscience. As President of the African Civilisation Society, he gave a speech demanding the slave trade be abolished.

He even got his wife to take up good causes, become patron of charities and help child workers. He got Lords to look at changing laws, and made Victoria think about subjects that otherwise would never have crossed her mind.

His death, which they reckon was due to typhoid, left Victoria utterly bereft.

Many say a walk in heavy rain with son Bertie, during which he gave him a rollicking for his immoral habits, made Albert ill, and he died weeks later.

Certainly, Victoria bitterly blamed Bertie for years to come, writing in her journals: “I never can or shall look at him without a shudder.”

She would find some solace in friendships, including as we know, with John Brown and servant Abdul, but Queen Victoria never truly got over the one love of her life.

To be fair, theirs is probably the greatest royal love story of them all.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe