How well do we remember, remember the fifth of November?

A new book looks at the monumental events of that date in the year 1605, when Guy Fawkes tried to kill the king and change the country’s political and religious direction.

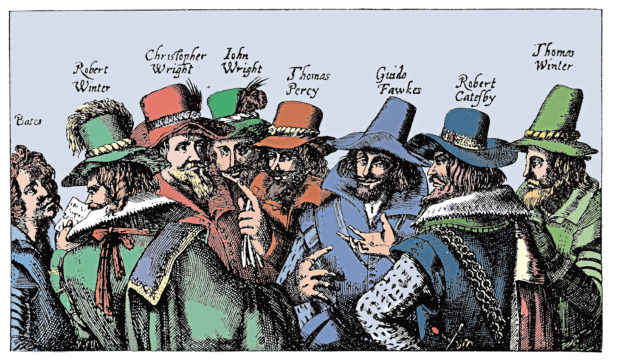

The failed assassination attempt against James I was made by a group of provincial Catholics led by Robert Catesby, who wanted to blow up the House of Lords.

This was to happen during the State Opening of Parliament on November 5, and as the news reverberated around the country, there would follow a popular revolt in the Midlands and James’s nine-year-old daughter Elizabeth would be installed as a Catholic head of state.

James Travers, an expert in history and English Literature and a subject specialist at the National Archives, studied original dialogue from the time to examine the astonishing events from a fresh perspective.

As he points out, the whole Guy Fawkes story has disappeared behind popular celebrations like Bonfire Night, only to reappear with modern-day rebels’ use of his popular image.

“Guy Fawkes is back,” says the author. “Adopted by the hacktivist internet group Anonymous, Guido Fawkes has become the face of political disaffection once again.

“Thanks to his popularity as a mask, he has reclaimed some of the original mystique and the nightmare quality associated with him -– the unknown face of the Plot, prized by the well-known and well-connected plotters as a man who could pass unnoticed in Westminster, even as he went to destroy the Houses of Parliament.”

Ironically, in the midst of such troubles, James I had actually tried to keep out of religious wars and ruled wisely and intelligently during a very creative time for the country.

Shakespeare, along with other geniuses such as John Donne, Ben Jonson and Sir Francis Bacon, were giving the world masterpieces that have beguiled and amazed millions right up to the present day.

As James points out, the very men who tried to bring the Government down and cause havoc would have been in the audience for the Bard’s plays.

“Drama was important in shaping how people at the time viewed these events,” he says, referring to the drama of the plotters being blown up with their own gunpowder, and to the clothing they wore as they went about it and the swords bearing images of Christ’s Passion.

“The plotters and their contemporaries were the original audience of William Shakespeare’s history plays – they could see played out in them the machinations of the court, the intrigues of the succession and the historical role of eminent families who still retained their traditional power to make and unmake kings.”

To millions of every age today, who enjoy or hate the fireworks, blazes, noise and wildness of modern events this week, there is often little knowledge about why it all started and what actually happened on that fateful day.

The previous month, Ben Jonson – a dramatist rated second only to Shakespeare – had attended a supper party with the majority of the plotters. Jonson would escape a long prison term, it is thought, by offering all he knew to the Privy Council.

The Establishment, however, was on to the plotters before the fateful day.

Among the tip-offs was a letter which, says James, “contained a thinly-disguised warning of some explosive enterprise against the opening of Parliament”.

Lord Monteagle, born William Parker, was the recipient of the letter, which read: “My lord, out of the love I bear to some of your friends, I have a care for your preservation. Therefore I would advise you as you tender your life to devise some excuse to shift of your attendance at this parliament.

“Retire yourself into your country, where you may expect the event in safety, for though there be no appearance of any stir, yet say they shall receive a terrible blow this parliament and yet they shall not see who hurts them.”

The meaning was pretty unmistakable, and they were more than ready when Guy Fawkes and his colleagues attempted their plot. Not that he was actually known to his captors by that name, as James explains.

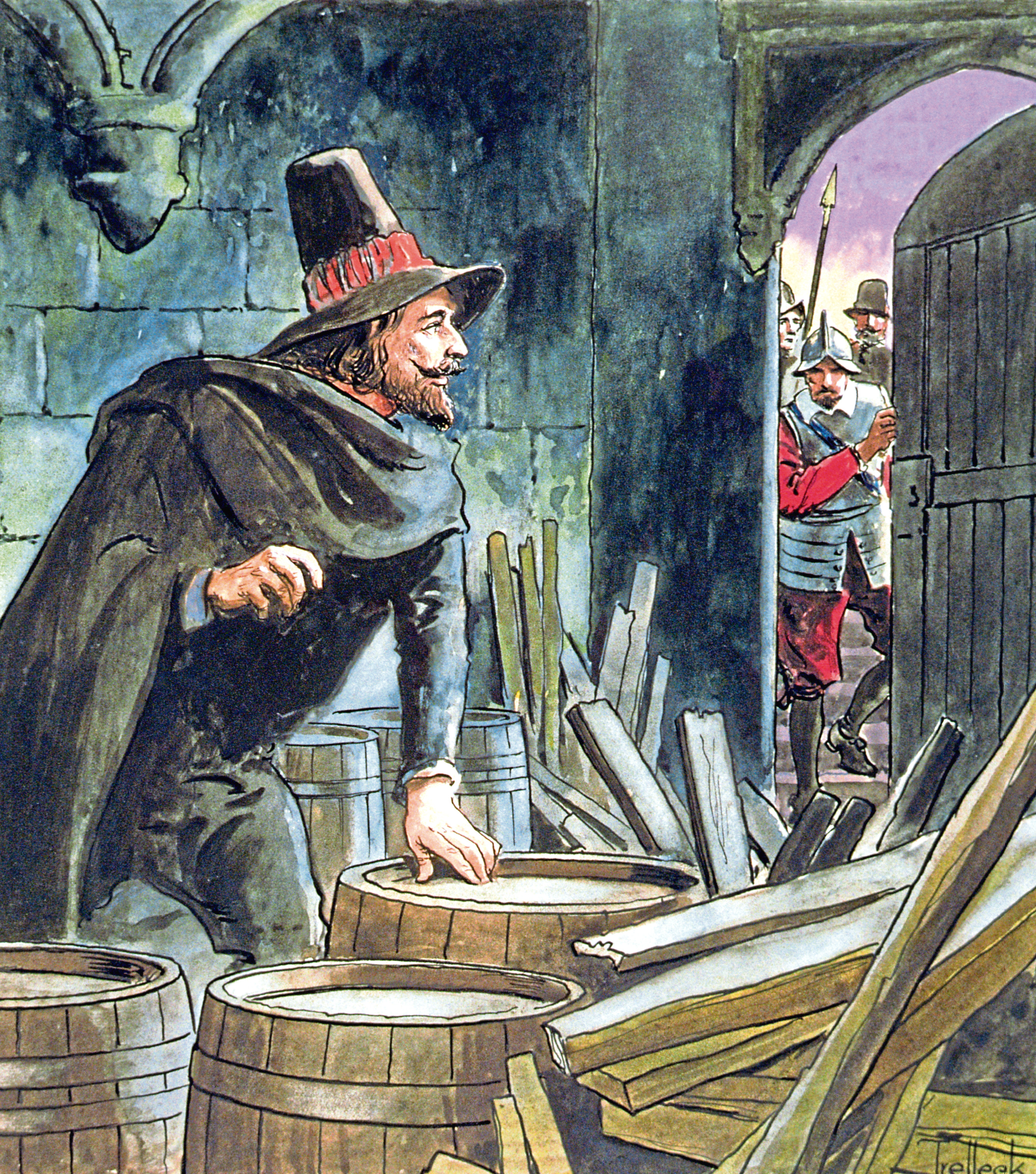

“Guy Fawkes in the vault below the House of Lords with his dark beard, dark lantern and barrels of gunpowder is the abiding image of the Plot and the focus of the November 5 celebrations,” he says.

“For some time, the authorities knew him only by the alias he gave, John Johnson, and for a long week after the discovery of the Plot, he was questioned alone in the Tower of London, the authorities’ only direct source of information.

“By the end of the week, it was clear that he was far from acting alone, but his status as the lone face of the Plot was established.

“Documents show his humanity, steadfastness and lack of repentance, making him a figure difficult to hate but also difficult to defend.”

After Monteagle got his letter, there followed a search of House of Lords, and Fawkes was caught guarding 36 barrels of gunpowder.

It was enough to bring the House down – literally. The game was up and most of his colleagues fled, attempting to gain support as they went.

Catesby was among those shot dead during a gun battle.

At a trial on January 27 the next year, eight were convicted, Fawkes among them of course, and sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered.

But some of the escaping plotters suffered the ultimate indignity, ironically, of being badly hurt by the powder.

“The remaining rebels arrived at Holbeach House, Staffordshire, on the evening of November 7,” explains James.

“They decided to dry their damp, currently useless, gunpowder before the open fire, only for it to explode, leaving Catesby and Ambrose Rookwood badly burned and John Grant nearly blinded. The others were badly shaken.

“This horrific explosion, rich in dramatic irony, finally raised in the minds of the conspirators the idea that God did not, after all, support their scheme.

“It was suggested to Catesby that they might take this signal of divine displeasure as a cue to end their hopeless situation, by blowing themselves up completely with the remaining gunpowder. The suggestion was not followed.”

Today you might think it was all just about fire and rebellion, dark deeds and a brutal end.

But James wonders: “What does the Plot tell us about the life of Shakespeare?”

“There are plenty of allusions to the Plot and its cross-currents evident in his plays, which suggests there was more in them to concern the playwright than a topical theme to raise a laugh or a shudder of horror in a knowing audience.

“Shakespeare is seen in glimpses at the edge of the Plot, alluding to its trials and evidence in Macbeth. But he is not quite in the right area of London when the Plot is hatched.”

Perhaps the story of the Gunpowder Plot will have yet more new revelations in centuries to come.

The Gunpowder Plot by James Travers is published by Amberley, priced £20.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Historica Graphica Collection/Heritage Images/Getty Images

© Historica Graphica Collection/Heritage Images/Getty Images