The final 36 islanders of St Kilda were evacuated on the morning of August 29, 1930, after more than a thousand years of continuous occupation. Hirta – by far the biggest island in the archipelago, 40 miles west of North Uist, the outer Outer Hebrides, far out in the Atlantic, the remotest inhabitable part of the United Kingdom – was to be abandoned. Soon, it would be a ghost island.

Historian Matthew Green has written Shadowlands, a book exploring the haunting shades of St Kilda and Britain’s other lost places. Visiting the towns, villages and islands lost to natural phenomena, war and plague, economic shifts and technological progress, he lays bare the precariousness of humanity.

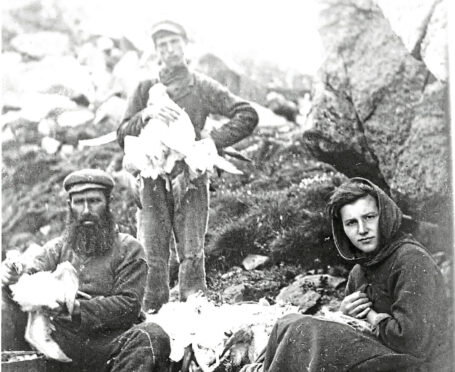

In this extract, the author remembers the final years of St Kilda before the dwindling band of islanders finally gave up, leaving their home to the seabirds.

One spring morning in 1918, everyone was horrified by the latest abomination offered up by the sea.

From the beach the villagers could have tossed a stone on to its fin but of course they pelted up the hills the second they saw it. Now, looming out of the blue, the whole village seemed to be in the shadow of destruction, the enormous steel whale which the gannets and fulmars were giving a wide berth poised to fire.

In fact, Commander Walter Remy of the German Imperial Navy had been pacing beneath the waves for several hours, dreaming of destruction.

He had been tasked with destroying St Kilda’s wireless station, which was being used to convey news of enemy ship movements in the Atlantic from the lookout posts on the island’s mountain peaks to British central command.

The submarine was armed with hundreds of shells and a machine gun, now pointing at the island’s row of houses. As Commander Remy peered into his periscope, St Kilda faced the prospect of complete annihilation.

The submarine pounded the village for nearly an hour. The cows and sheep rushed from one side of the island to the other in terror. The two wireless masts behind the factor’s house were blasted to bits early on in the assault but the German commander turned out to be merciful, warning those islanders still inside their houses, by loudspeaker, to get the hell out or face imminent destruction.

More than 60 shells were fired. The church and manse were destroyed, along with two cottages and a storehouse, and two boats were ruined beyond repair. And, with that, the ship slipped beneath the waves and disappeared.

It could have been a lot worse: the death toll was just one lamb. It was the first time, however, that St Kilda had become embroiled in the maelstrom of violence that had seized the outside world, further relieving them of the notion, if anyone still believed it, that the island could exist as a self-contained entity.

Later that year, a solitary mounted gun was installed above Village Bay to be greased and polished by the postmaster each month and such a formidable deterrent it was, it was never once fired.

After the First World War, St Kilda fell into a death spiral. The 16 sailors on secondment departed, but their stories of life in London, Glasgow and other parts of Britain lingered on in the islanders’ imagination, compounding a pre-existing sense of wanderlust.

Between 1919 and 1920, a quarter of St Kilda’s population was lost to the prospect of employment and a better life on the mainland. That these émigrés were all young was ominous because, as we have seen as far back as the Stone Age, the haemorrhaging of youth from a community is a harbinger of its desiccation and demise. And so the wheel turned. Crops failed.

Alien vessels brought disease and conveyed news of the Hirtans’ pitiful state to the outside world. In 1926 the whole island was laid low by flu; no fires burned, no dogs barked, and the bells in the chapel fell still. Only the wind kept up its sour lament.

On the first day of the outbreak some islanders lit a fire on a hill, but no trawlers passed by. By the fourth day, when the HMS Hebrides finally appeared on the horizon, four islanders were already dead.

One islander had to wrench planks of wood from an old woman’s ceiling to make her a coffin; such was the scarcity of timber.

The man who performed this inventive piece of carpentry was called Lachlan MacDonald. Like so many other young and able-bodied Kildans, he felt trapped. His father had drowned in a climbing accident years earlier and it fell upon him to look after his disabled mother.

A trip to the mainland one summer brought home how monotonous was his life. “There was nothing there,” he recalled, “no enjoyment…just working from one day to another, even nights.”

Already the dominoes were falling. A couple of years earlier, William Macdonald (no relation) had become the first Hirtan to remove his entire family, their permanently locked door a dark prognostication of things to come, and one day in 1925 the minister Donald John Gillies upped and left aboard the HMS Hebrides for Canada.

These prompted a cascade, a flight of the able-bodied. In his report from May 1928, the police constable from the isle of Harris described a community in free fall, with a population now of just 37, a rump dangerously reliant upon imported food; the fulmar broth and gannet eggs now seemed to yowl of yesteryear.

The next year brought a winter of hell. In October 1929, a passing fisherman found the islanders bleeding and itching with blisters brought on by eczema. The Board of Health did nothing because they had not heard directly from the official channel, Nurse Barclay, never mind that she was laid low herself.

Mary Gillies, 35 years of age, was the mother of the diarist Norman Gillies. She had an expressive face with free-flowing black hair, and in 1930 was pregnant with a daughter. Her appendix burst one day in the spring of 1930. True to form, the government’s response was slow.

An attempt to rush a doctor to the island in May proved abortive, so a woefully ill-equipped Nurse Barclay had to tend to the ailing woman herself. It took a further two weeks for the government to arrange for a fishery cruiser from Harris to transport Mary to the mainland for urgent medical attention.

“I can remember her being taken off,” recalled her son, “on to the boat, and me standing near the pier with my grandmother and waving to her and she’d got her shawl round her head and was waving back” – but she died two days later in a ward in Glasgow. Mary’s sad end strengthened Nurse Barclay’s argument, in a letter to the Board of Health, that St Kilda was no longer fit for human habitation.

When the Henry Malling rolled in, as spring bloomed in 1930, it found a community in the throes of death, suckling on the sugary provisions that they bore like half-starved animals and devouring sacks of letters and newspapers for some glimmer of hope from the outside world.

Some children had spent the winter barefoot and were delighted to put on laced boots. They found that only one islander had bothered to sow crops for the winter, such was the general climate of resignation.

Evacuation was not a new idea but the likelihood of it actually happening had never gained much traction, until now. When it had been suggested the previous year, one old woman declared she would never move unless physically forced to do so. Yet one year later, following the tragic winter, the idea of remaining on St Kilda seemed hopeless, masochistic even.

“They have gone through such privations this winter,” observed Skipper Quirk, “that they don’t want to face another.” It was these arguments that won the day when, at the factor’s house in April 1930, Nurse Williamina Barclay convened a grave tea.

The remaining islanders were to discuss the prospect of evacuation. With their autarky in ruins, a grim finality set in. “Between you, me and the deep sea,” said Williamina at this final summit, “I think you’re on your last legs.

“We sat down at the table for hours, and one old man with the tears trickling down his face came and put his arm around my shoulder. ‘We all think God sent you here.’” She had told them another world was possible. A world where you do not have to struggle just to survive.

A world where the children would have a chance in life. And so there was consent. The minister Dugald Munro sat down, took a piece of scrap paper, and composed a petition – a prayer – to the Secretary of State for Scotland.

His request was workmanlike and devoid of elegy. The population was now just 36, he said, of which a significant proportion were determined to leave. There would not be enough able-bodied individuals to tend the sheep, to weave, to look after the widows, to eke out even a meagre existence.

Since the island was no longer self-sufficient, they needed the government’s help to remove themselves and their possessions and “to find homes and occupations for us on the mainland”.

After 2,000 years of continuous occupation, the Hirtans had become shipwrecks on their own island. The petition was signed by all the adults on the island – 12 men, eight women – and handed to the next trawler to appear in the bay. Then they waited and prayed for the wheels of bureaucracy to turn, delivering them from their certain ruin.

Four days before the evacuation, in the dying days of August 1930, the final postcard was sent. Its message, from a tourist called Freda, said, just, “Last Greetings from St Kilda”.

Then the post office shut for ever, the final service was held at church and, bowed by sorrow, the islanders rounded up their dogs, those indomitable hunters and guardians, tied weights around their necks, placed them in sacks, and dropped them from the pier, looking sorrowfully on as the yelping bundles sank beneath the waves. Then they returned to their houses and waited for HMS Harebell.

And up on the stacks of Boreray, from their nests in the cliffs, the birds rejoiced.

Shadowlands: A Journey Through Lost Britain by Matthew Green is published by Faber on March 17

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Shutterstock / corlaffra

© Shutterstock / corlaffra © Shutterstock / Martin Payne

© Shutterstock / Martin Payne