When we hear the word ‘bikini’ the first thing that springs to mind is scantily clad women frolicking on a beach.

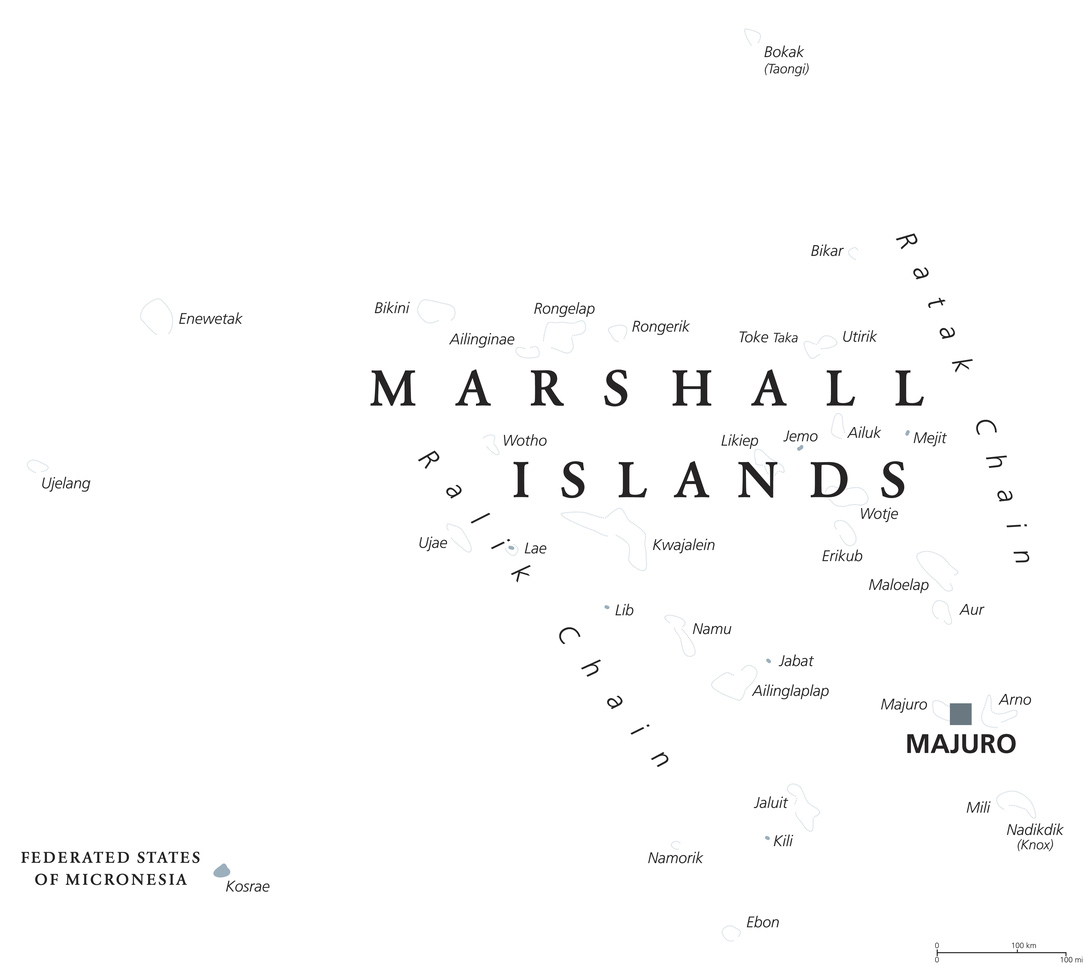

Before the invention of the bikini swimsuit in 1946 however, Bikini was simply an atoll of 23 small islands and coral reefs in the Marshall Islands of the Pacific Ocean.

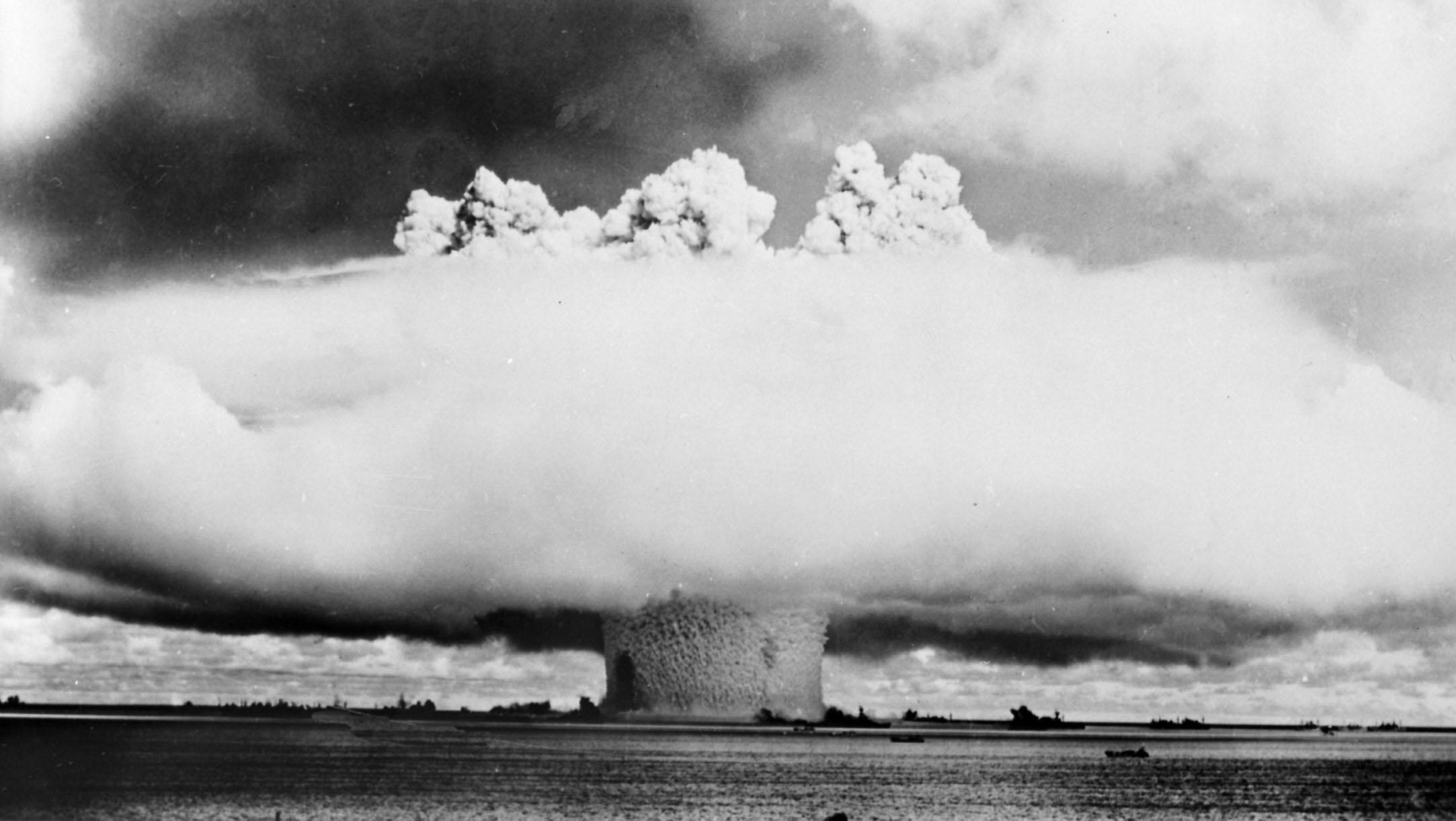

The swimsuit was named after the bombings that occurred on the islands of Bikini on 1 July 1946. Likening his swimsuit to a ‘bombshell,’ its designer Louis Réard perhaps didn’t realise the true devastating effects the bombs would come to have on the Bikini atoll and its inhabitants.

Nuclear bombs were dropped 23 times between 1946 and 1958 on the Bikini atoll, creating huge craters in the reef and rendering over 28 species of coral extinct.

Bikini was distant from both regular sea and air traffic, therefore making it an ideal location for testing the nuclear bombs. In February 1946 the 167 Micronesian inhabitants of the atoll were asked to voluntarily and temporarily relocate so the United States government could begin testing atomic bombs.

After “confused and sorrowful deliberation” among the Bikinians, their leader, King Juda, agreed to the U.S. relocation request, believing that they would eventually return to their island.

They relocated to the uninhabited Rongerik Atoll, but it could not produce enough food and the islanders starved.

When they could not return home, they were relocated to Kwajalein Atoll for six months before choosing to live on Kili Island, a small island one-sixth the size of their home island.

They soon learned however that they could no longer fish the way they had on Bikini Atoll. Kili lacked the still and protected lagoon of Bikini.

Before the beginning of Western influence, the Bikini islanders’ lifestyle was based on cultivating native plants and eating shellfish and fish. They were highly skilled boat builders and navigators, sailing to and from islets around the Bikini and other atolls in the Marshall Islands.

The islanders were relatively isolated and had developed a well-integrated society bound by close extended family association and tradition.

After the bombings, fish in the region had now become completely poisonous, due to the aftermath of the nuclear testing. Coconut crabs, a staple of the Bikinian diet, were also found to have too high levels of radiation to be eaten.

Living on Kili Island effectively destroyed the Bikinian culture that had been based on fishing and island-hopping canoe voyages to various islets around the Bikini Atoll. Kili again did not provide enough food for the transplanted residents and many died as a result.

Throughout the aftermath of the bombings, women were experiencing miscarriages, stillbirths, and genetic abnormalities in their children, thanks to the high levels of radiation still prevalent.

Today, the Bikini islands are still uninhabitable, suffering highly at the hands of climate change, its descendants remaining in exile on the Kili and Ejit islands, approximately 500 miles to the southeast.

Recent research suggests that rather than the rising sea levels simply swallowing these islands, enornmous waves crashing over them will ruin freshwater supplies for residents as soon as 2050.

Unless extensive conservation efforts are put in place by the US government, the Bikini and surrounding atolls of the Marshall Islands – their cultures, islands and history – may soon be a thing of the past.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe