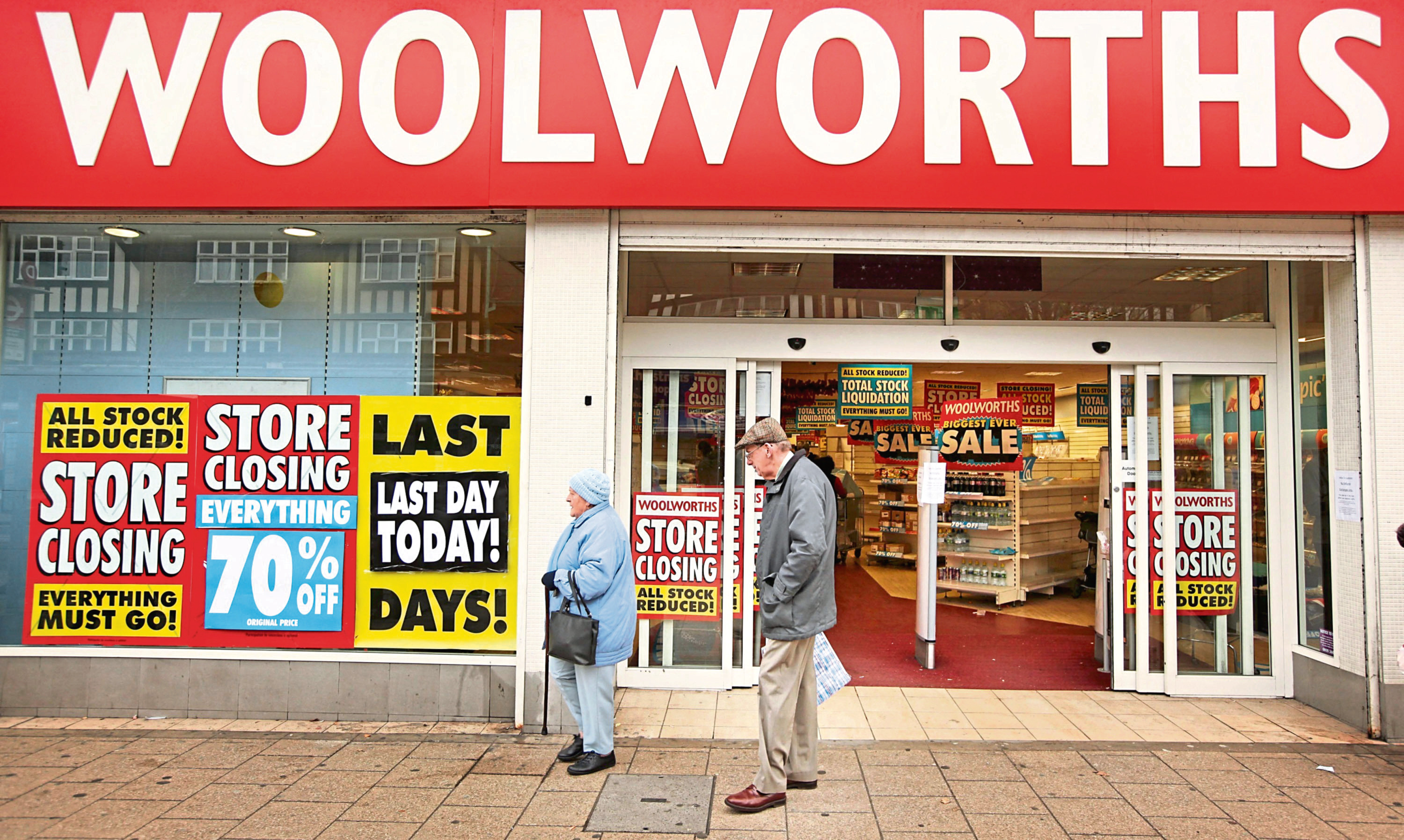

BRITAIN’S high streets have had a rough time over the past couple of decades with many familiar names disappearing and many more still under threat.

Of those that are now defunct, perhaps the most emotional attachment was to a unique store that ruled UK town centres for 100 years.

Ten years ago, Woolworths closed its doors for the final time, having come to these shores from America back in 1909.

At its peak, the company had 807 outlets, but in November 2008, it went into administration with debts of £385 million.

To anyone growing up in Britain in the last century, a trip to “Woolies” was a magical experience.

As kids we would make a bee-line to the Willy Wonka-like pick ’n’ mix or try weighing ourselves on one of those huge red scales that seemed to occupy a position at every front entrance, while mum and dad stocked up on everything from stationery, light bulbs and records to crockery, tools and underwear.

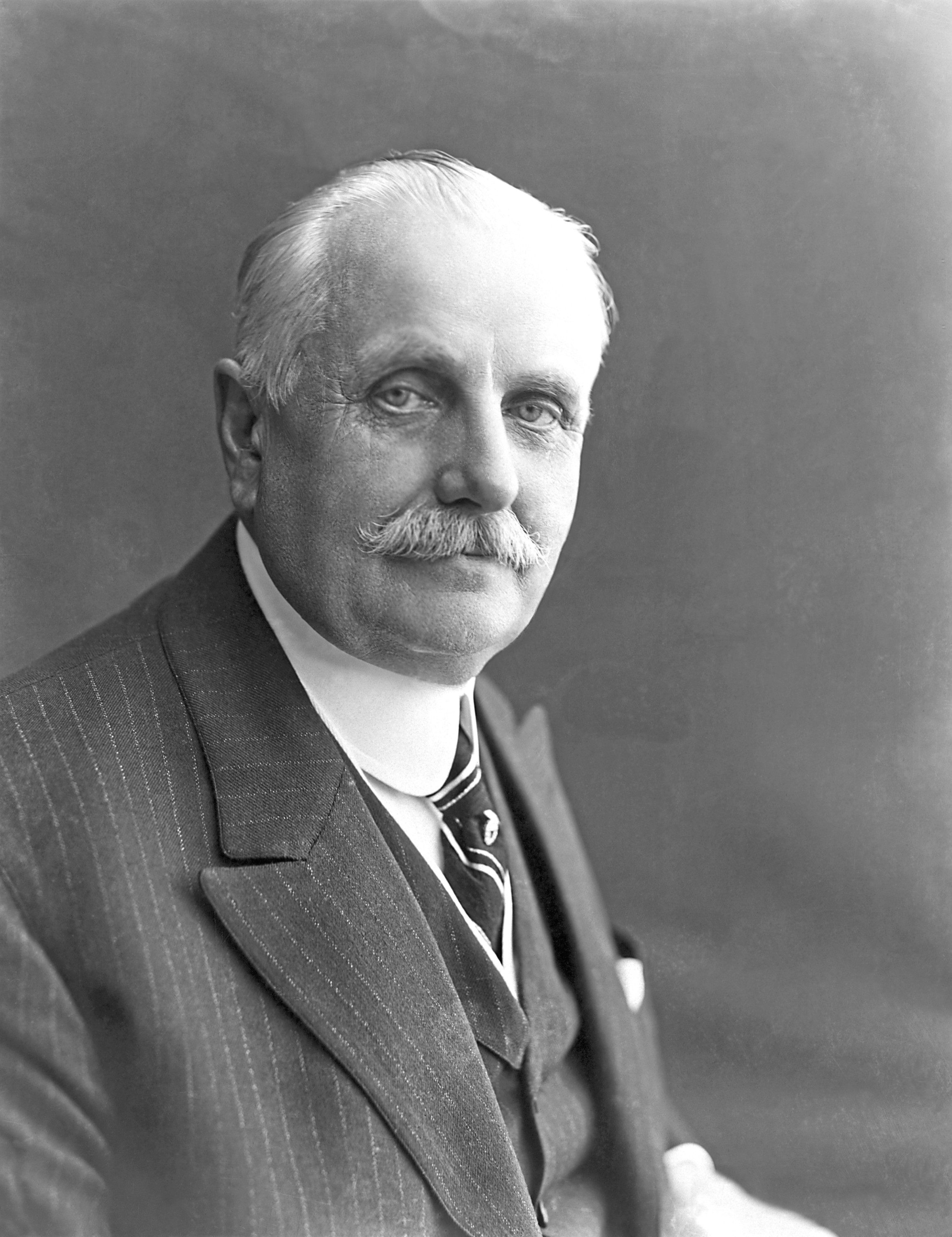

The origins of Woolworths go back to Watertown, New York, when 15-year-old Frank Winfield Woolworth left the family farm to work at the Augsbury and Moore Dry Goods Store.

He studied commerce and book-keeping at night school until his boss, William Moore, put him in charge of display and stock management.

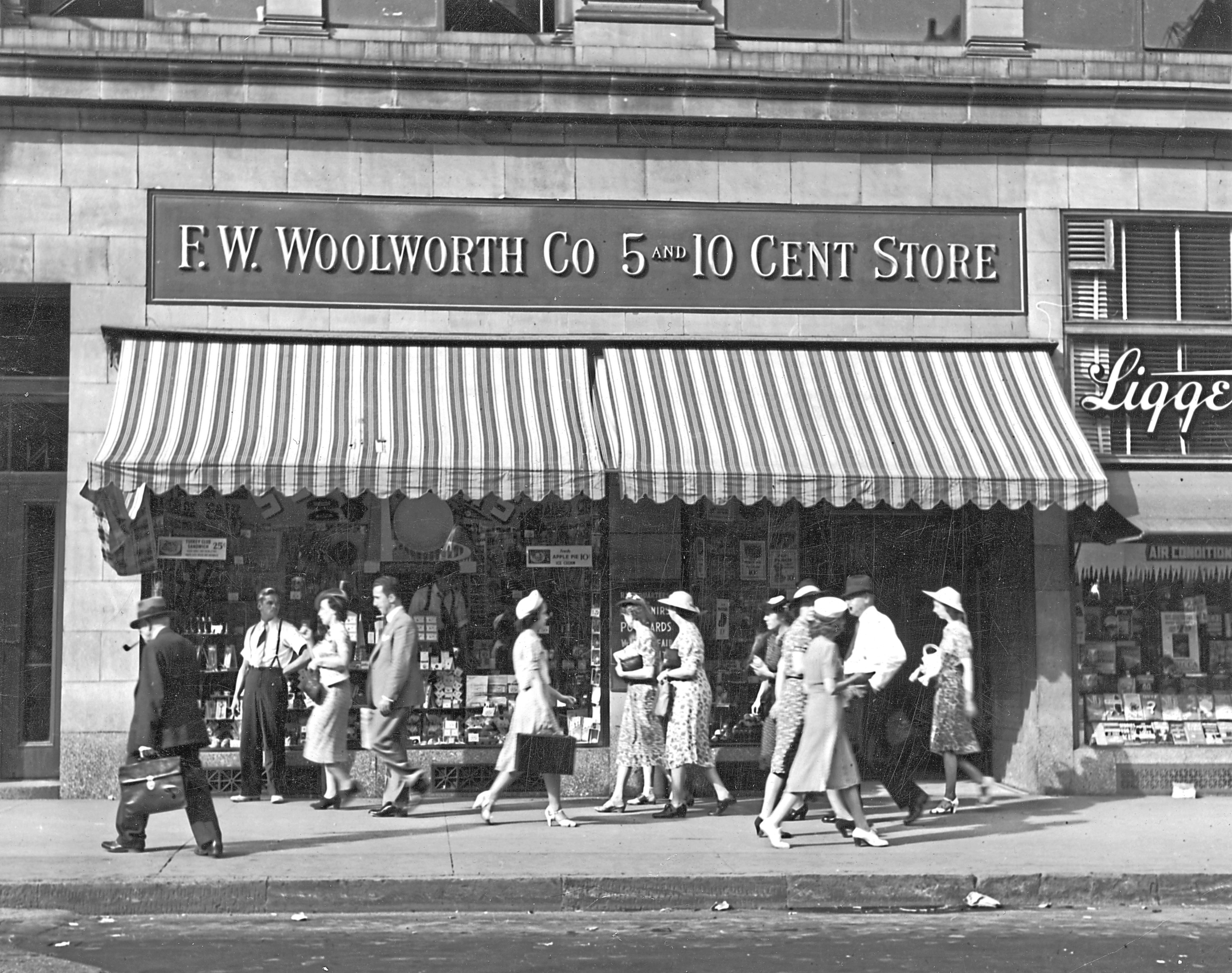

One of Frank’s jobs was to set up a table of fixed price five cent goods, which proved such a hit that in 1879, he branched out on his own, setting up one of America’s first fixed price stores in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

His younger brother, Charles, joined as manager of a second store in nearby Harrisburg.

Ten cent lines were added in 1881, creating the first Five and Dime store chain.

He brought in more members of his family, who opened their own stores, and soon there were dozens of five and dimes across the US and Canada.

In 1912, these were brought together as FW Woolworth and Co.

Explaining his success, Woolworth said: “I put it down to the great buying power that allows us to drive prices lower by helping factories to make their goods more cheaply.”

It was a strategy which proved hugely successful: good-quality items at affordable prices.

Woolworth visited Britain and became convinced that he could recreate the five and dimes, saying: “I believe that a good penny and sixpence store, run by a real-live Yankee, would be a storm here.”

On November 5 1909, Frank opened his first store outside North America.

Five and Dime became Threepence and Sixpence for the branch in Church Street, Liverpool.

The Liverpool branch was quickly followed by stores in Preston, Manchester, Leeds and Hull and as the chain expanded, a restaurant was included in each large store.

The firm aimed to promote shopping as a leisure activity and believed that by selling good food at low prices it would allow people more time for shopping.

Frank hired his cousin, Fred, to lead the new British venture. The American parent company put up £50,000 capital to finance the UK chain.

By 1912 the British subsidiary had already grown to 12 stores, its momentum so great that Frank could turn his attention to other projects – notably the construction of the world’s tallest building in Broadway Place, New York.

He paid $13.5 million for the landmark Woolworth Building that dominated the Manhattan skyline.

The founder’s long-term goal for the British venture was a branch in Oxford Street, which would show his countryman, Gordon Henry Selfridge, how a store should be run.

Brixton, then an affluent suburb, was the starting point, but by the time the flagship Oxford Street store opened in 1924 it was the 161th Woolworth’s in the UK.

Frank didn’t get to see it as five years earlier he died from septic poisoning due to a tooth infection.

One notable obituary read: “He made his money not by selling a little for a lot, but by selling a lot for a little.”

And the year before the Oxford Street store opened, the firm was rocked by another death, Frank’s cousin Fred, MD of the British subsidiary, who was just 52.

By then he’d overseen the opening of 150 highly profitable stores, had a reputation for setting high standards but also treating the staff generously, with paid holidays and outings to the seaside.

His successor was Yorkshireman William Stephenson, who instigated a massive expansion project. At one point in the 1920s a new store was opening every 17 days.

Each opening was organised according to a tried and tested formula with plenty of razzmatazz.

There would be music, fireworks, flags, bunting, a band and circus performers and free tea and cakes.

People flocked to the stores and there was even a song entitled We’ll Have A Woolworths Wedding.

In the 1930s, Woolworths started selling items such as gramophone records and Directoire knickers, which retailed for four shillings a dozen.

They later introduced a range of children’s clothing which became known as Ladybird.

However, the best seller was Bravisco artificial silk underwear which sold in huge quantities.

Perhaps the most iconic, and certainly the most photographed, Woolworths store is the one that sat at the foot of Blackpool Tower.

Its art deco facade, with its distinctive clock tower, featured on every seaside postcard after its opening in spring 1938.

It was Woolworths’ most ambitious British building, helping the Tower to dominate the skyline.

There were three sales floors and two 2,000-seat restaurants on further levels.

The upper facility was mainly reserved for private parties, but gave the capacity required for tourists visiting the town during wakes weeks when all local industry shut down.

Woolworths offered dishes for sixpence and a full three-course meal for two shillings.

This year also marks the 40th anniversary of one of the darkest days in Woolworths’ British history.

In May 1979 a huge fire at the Manchester city centre store in Piccadilly Gardens claimed the lives of 10 people, while 47 were taken to hospital.

Six firemen were injured as they rescued 26 people trapped inside the six-storey building.

Around 500 customers were believed to have been in the store at the time and when crews arrived they found thick smoke billowing out and people screaming for help from upper floor windows.

Firefighters fought the blaze for two-and-a-half hours while helping people escape via the windows and roof.

An investigation showed the fire was caused by a damaged electrical cable which ignited furniture made of polyurethane foam, which in turn produced large amounts of toxic smoke.

The store had no sprinkler system, and there were thick bars on the upper-floor windows that needed specialist cutting machinery to remove.

The fire was largely responsible for the change in the law obliging furniture makers to use flame-resistant foam.

For the company, the Manchester fire must have invoked memories of another, if altogether different, disaster.

On Saturday November 25 1944, as the Allies pushed on towards Berlin, word swept across London that Woolworths’ New Cross store had received 144 tin saucepans.

Such items were scarce and queues built up quickly. At noon the council’s manual workers clocked off after collecting their wages from Deptford Town Hall opposite the store and went shopping.

Also at noon, far away on Walcheren Island off the Belgian Coast, a group of German dignitaries were gathering to mark the 250th launch of a V2 rocket, which was despatched skywards as they watched.

A few minutes later it malfunctioned and exploded in the sky above St Paul’s Cray in Kent. No-one was hurt.

At 12.15 train cleaners from New Cross Station slipped off early, hoping to get one of the saucepans – and the 251st rocket was launched.

At 12.26 the V2 hit the rear of the flat roof of the Woolworths store. The building collapsed and exploded. People waiting for a tram in the street outside were caught in the inferno.

It is believed that the station had been the target.

In the store, 168 people had died, while 122 passers-by were injured.

In common with many other high street stores, Woolworths’ slow decline began around 1980 as the retail world changed, and not even the special place it held in the hearts of British shoppers could change its fate.

The market for physical copies of music, one of Woolworths’ main money-spinners, shrank in the early 21st Century and the major supermarket chains expanded into many of the company’s product areas.

Then, of course, came the internet and the final death blow.

No-one, however, will ever forget The Wonder Of Woolies.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe