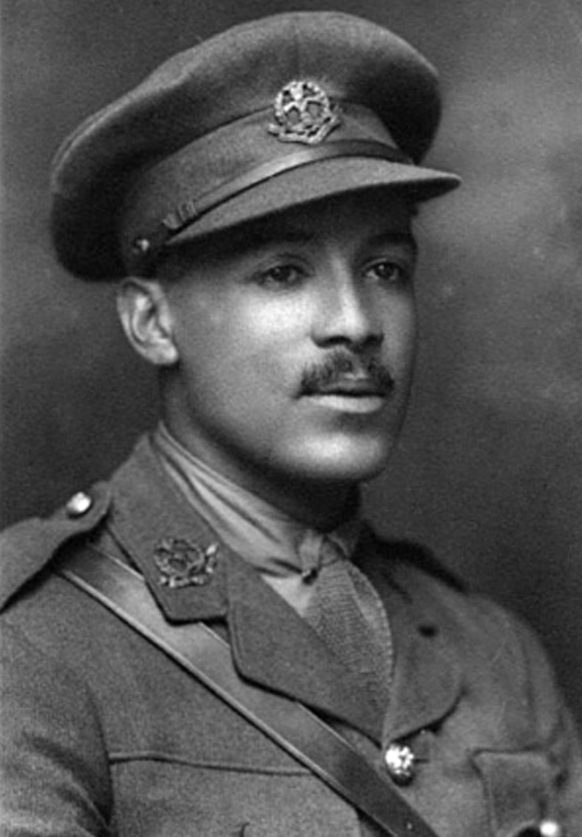

HE was the first black player to be recruited by Rangers, and the British Army’s first ever black officer to command white troops.

And on Sunday, 100 years after the year of his death, Second Lieutenant Walter Daniel Tull is being commemorated at Ayr Beach, as part of Danny Boyle’s Pages of the Sea nationwide remembrance project.

Cited as one of Britain’s most unknown and underappreciated war heroes, Walter’s life was one of adversity, but an adversity that he frequently overcame.

Walter Daniel John Tull was born in Folkestone, Kent in 1888, ironically a place which had significant ties with the WW1 effort.

His father was Daniel Tull, who came to Britain from Barbados in 1876, working as a ship’s carpenter. His grandmother Anna Lashley is believed to have been born as a slave on a Caribbean plantation.

Walter’s white mother, Alice, was from Kent. Letters exist from her mother, writing to Daniel welcoming him into their family.

In 1895, when Walter was seven, his mother Alice died of breast cancer. Shortly afterwards, his father married Alice’s niece, Clara Palmer.

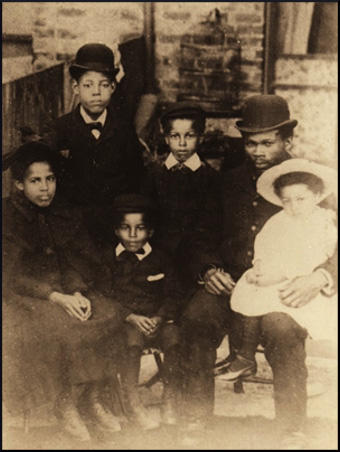

Soon after the birth of their only child, Daniel died suddenly of heart disease, leaving Clara to support seven children. In the absence of the welfare state, she was unable to cope or financially provide.

As a result, Walter and his brother Edward were taken into Dr Stephenson’s Children’s Home in London, a Wesleyan Methodist institution.

The family was broken up and while Edward was adopted by a dentist and his family in Glasgow, Walter remained in England.

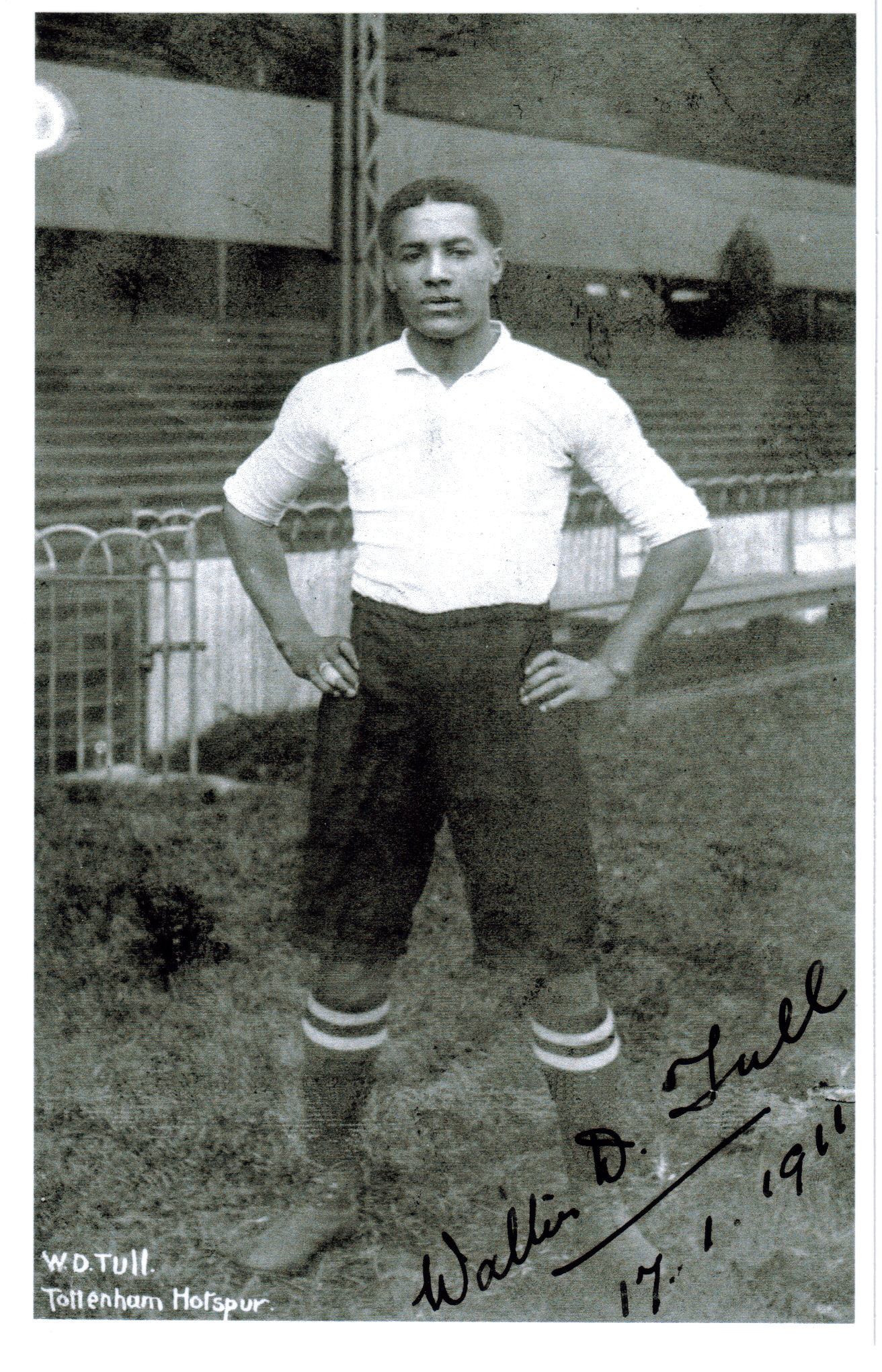

He turned his interests to football and by 21 was an aspiring inside-forward. According to Rangers historian David Mason: “He joined Tottenham Hotspur for a fee of £10.

“He played 20 times for Spurs before being signed by Northampton in 1911 for what has been described as a substantial fee.

“Apparently, it was his intent to play for Rangers when the war ended, bringing him closer to brother Edward and sister Cissie who had been welcomed into the family of Edward’s adoptive parents.

“But he returned to the Flanders fields fighting in the Battle of Messines just four months after signing at Ibrox.”

Although an extremely accomplished professional footballer, Walter dealt with substantial racism while playing for both Spurs and Northampton from opposing fans. One newspaper report from 1909 reported that in a match with Bristol City, “a section of the crowd made a cowardly attack on him in language lower than Billingsgate [fish market].”

The racism didn’t stop with his football career. His command as an officer in the First World War caused consternation in army circles as it was in direct conflict with the 1914 Manual of Military Law which excluded non-whites from exercising authority.

“The army from Britain was almost exclusively led by white men,” said Derek Patrick, lecturer in history at St Andrews University.

“It was made all the more difficult for anyone of colour to move up the ranks at this time period thanks to specific rules in place which determined anyone in command must only be of European descent.”

Walter’s brother Edward also faced discrimination and prejudice after being trained as a dentist by his adoptive family.

Edward’s granddaughter Pat Justad who lives in Strathpeffer remembers a story she was told of significant racial prejudice towards her grandfather. She said: “He was travelling to a city in England from Glasgow, hoping to embark in his first job as a dentist.

“He’d taken the precaution of sending a photograph of himself beforehand, just so they knew exactly what he looked like, which is quite terrible in itself.

“However, when he got there, he was told that if the dentist were to employ him to operate on patients, he would destroy his practice within 24 hours. He was then told to leave the premises.”

But it is Walter and Edward’s strength of character and success in spite of prejudice and adversity that their family now want to remember.

Walter was revered by his peers, even after death. After he was killed by machine gun fire on 25 Match 1918, several of his men are said to have risked their own lives in an attempt to retrieve his body under heavy fire.

Walter was also recommended by his comrades for the award of the Military Cross for acts of bravery and members of his family have been lobbying for it to be awarded posthumously. But it is his legacy of inclusivity that they value most.

Tull’s great grand-nephew, Tor Justad said: “It is Walter’s overcoming of prejudice and discrimination that for me personally should be most commended. I hope as people continue to learn about his life, it can only promote positivity and a shunning of inequality based on heritage.

“Although no doubt he was the subject of racial abuse, the fact that he excelled both in a sport and in an army that was dominated by white men shows significant strength of character.

“I hope his life continues to act as a beacon of strength to young people growing up of what can be done even in the face of total adversity.”

Walter’s life will be commemorated on Sunday 11 November at Ayr Beach through a large-scale portrait drawn in the sand by artists in the Pages of the Sea Project.

Find out more here.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe