It was 10.24pm on Saturday, May 10, 1941, as the beetle-browed German’s twin-engined Me-110 snarled over the coast, all but skimming the roofs of sleepy Bamburgh.

He turned once, then twice, looking for a loch here and a notch in the hills there, till finally he might sight the stately home – Dungavel House – where, in short order, he would meet the noble lord, deftly negotiate, and take Britain out of the Second World War before returning to Berlin and a hero’s welcome.

But it was now too dark to make the mansion out. The Nazi grunted. He had planned for this contingency and set course for the Firth of Clyde, where he would more readily get his bearings. He met the sea at West Kilbride; never forgot the “fabulous picture” of Little Cumbrae amidst the scarlet glow of sinking sunset.

And, yes, there was that railway – this he had memorised – and the 47-year old turned once more, following the glinting tracks back into the Scottish countryside, looking for the particular bend nearest Dungavel, and with but two trivial concerns – making his rendezvous before the Messerschmitt’s fuel ran out, and then safely parachuting to the ground.

It was now or never as fuel-warning lights lit. He pulled back on the control column and roared up, up, up to 2,000 feet, and then slid back the cockpit canopy.

But the onrush of air was too strong for him to clamber out. He now flipped the aircraft upside down, hoping to drop out. But he pushed the column the wrong way and the plane wailed into a groundward loop, with such centrifugal force that he briefly blacked out.

He came to as the Me-110 completed the loop, standing on its tail – and it was then Hitler’s deputy threw himself out, banging his right foot, and moments later tugged his ripcord. “The harness tightened, I hung,” he would remember, “an indescribably glorious and triumphant feeling in this situation.”

David McLean, head ploughman at Floors Farm, Eaglesham, saw someone float down from the night even as a plane exploded in a fireball of flame. He clutched his pitchfork the tighter, and went to help.

“British or German?” he asked, undoing the parachute harness. “German,” said his visitor, and then – lying – “Hauptmann Alfred Horn. I must go to Dungavel House. I have an important message for the Duke of Hamilton.”

And that was all he kept saying, even as he limped to the McLean cottage. “Where is the Duke of Hamilton? I must see the Duke of Hamilton…”

Rudolf Hess’s dramatic landing in Scotland was so bizarre Churchill himself at first refused to believe it; so incensed Hitler that he stripped his deputy of all honours, flung unfortunate Hess adjutants into concentration camps and privately ordered that, should the fool ever return, he was to be shot at once.

Eighty years later, we are yet bewildered. Why did Hitler’s deputy steal an aircraft and fly all the way to Scotland with a hare-brained peace-plan? Whom did he really wish to meet? Why are so many facts disputed? And why are our rulers so jumpy about it all that many relevant files are still sealed?

For sure, that descent to the green fields of Renfrewshire afforded the last happy moments Hess would know. He would spend nearly half a century a captive before apparently hanging himself – even death would not spare him further ignominies.

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess was born in Egypt in 1894, the firstborn of a wealthy German couple but would not see that country till sent there for senior schooling. He served in the army during the Great War – twice wounded – then trained as a flyer.

But, after the Armistice, Hess spent most of his time handing out vile anti-Semitic literature and indulging in Berlin street-fights. In 1920 he went to hear Hitler speak, was immediately smitten, fast won the demagogue’s trust and became his closest aide, bagman and secretary.

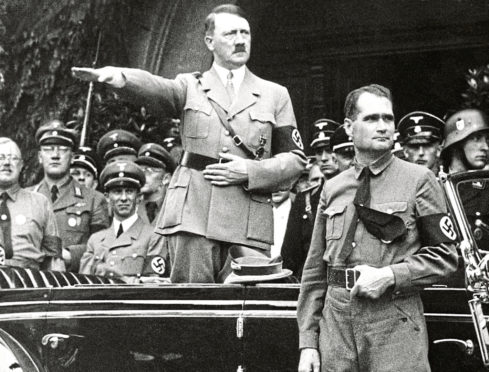

Grasp that, even as Deputy Führer from Hitler’s ascension to power in March, 1933, Hess was so thick as to be less a comrade than a sort of pet. His chief role was to stand and stare adoringly at Nuremberg rallies – “A man of limited intelligence,” noted William L Shirer, “always receptive to crackpot ideas…”

Several serious accounts of the Third Reich do not even mention Hess. By his forties he was a hypochondriac, a vegetarian, and fascinated by astrology and the occult. So many were his imagined ailments that, among the effects he took on his flight to Scotland were 28 different medicines.

The Duke of Hamilton, a senior RAF officer, was mortified as he hastened the following day to Glasgow’s Maryhill Barracks, where Hess was held. The two men met alone, where the bewildered aristocrat first heard the madness.

Germany would give Britain a free hand in the Empire – though wanted her old African colonies back. Oh, and Hess would not negotiate with this British Government – they must form a new one; and should the British not obediently sign up to such terms, they would be bombed to soot, starved to death – and so on.

He was nevertheless, Hess insisted, “on a mission of humanity.” He protested “his sincerity, and Germany’s willingness for peace.” So, might the King grant him parole?

That weekend, Hamilton talked with Churchill himself at Ditchley. On Monday he joined him with members of the War Cabinet; and then – with foreign affairs expert Ivone Kirkpatrick – had another long session with Hess, now in Buchanan Castle. Kirkpatrick met Hess twice more – but it was obvious, by now, that Hess in no way spoke for the German government.

Rudolf Hess had nothing to negotiate with and, discounted, faded away in captivity – briefly at the Tower of London, then for 13 months at a camp in Surrey (he hated it) and then in a hospital in Wales, where he was allowed newspapers and a radio, and even granted chauffeur-driven jaunts around the countryside.

By the end of October, 1945, he was on trial in Nuremberg, so evidently a broken man of doubtful capacity that the judges spared him the death sentence.

He was condemned merely to life imprisonment for crimes against peace and, by the end of July 1947, Hess was in Spandau and nuttier than ever. He would refuse, for instance, to meet any members of his family until 1969, and from June 1941 had made a succession of half-hearted suicide attempts.

From 1966, Hess was the last Nazi in Allied imprisonment and, as USSR soldiers took their quarterly turn in guarding him, this was a West Berlin gig they would not relinquish, even as the pathetic old man’s incarceration increasingly turned the world’s stomach.

“I am glad not to be responsible for the way in which Hess has been and is being treated,” Churchill had once rumbled. “He came to us of his own free will and, though without authority, had something of the quality of an envoy. He was a medical and not a criminal case and should be so regarded.”

The Soviets had no such concerns. At their insistence, Hess was only allowed to wash his hands in the toilet bowl; he was never addressed, even by British or French or American guards, as anything other than “Prisoner Number Seven.”

Then arose Mikhail Gorbachev and the tender breeze of glasnost. The Soviet government began to entertain talk of Hess’s liberation – and then, on August 17, 1987, his nurse and orderly returned from lunch to find the 93-year-old dead in a garden gazebo in the grounds of Spandau – and with two male strangers.

They insisted they had found him hanging from a length of electric flex secured to a window frame; wanted to revive him. Indeed, they massaged his chest with such enthusiasm bones cracked. There were some signs of struggle, Hess had mysteriously hanged himself from a point in the gazebo lower than he was tall – and why attempt suicide in the garden, where he could have been found at any moment, than in the privacy of his cell?

The German autopsy suggested not hanging, but garroting. The horns of his thyroid cartilage were broken; the bruising on his neck, too, was consistent with strangulation, not suicide. The British autopsy concluded otherwise and the case was closed.

There are still wilder theories about Rudolf Hess – that there was a serious bid for Anglo-German peace in the summer of 1941; that he had muddled up his Dukes and was looking for a senior member of the Royal Family; that the real Hess was murdered during the war and the man consigned to Spandau was not him but a brainwashed body double.

DNA evidence finally disproved that nonsense in 2019. But there were never even tentative talks between London and Berlin. Churchill had decisively shot that fox in June 1940, and the careers of politicians who had pressed for peace – like RA Butler – were perpetually clouded.

It is obvious from Hitler’s apocalyptic response to the Hess mission that it came to him as utter surprise and had not been authorised. And we can, to a large degree, understand why Hess did it.

Essentially a Nazi Party man, war saw him rapidly eclipsed by others, fading from the Führer’s favour, and desperate for a chance once more to shine. How about this brilliant stroke of statesmanship? And had not one of his astrologers even shared a vision of Hess delivering peace?

But, in 2004, strong evidence emerged that Hess had fallen victim to a British sting operation. In 1940, at his urging, a German Foreign Ministry official, Albrecht Haushofer, had written the Duke of Hamilton proposing a meeting in Lisbon.

This MI6 would not sanction but in February 1941 its recent and wily Berlin operative, Frank Foley, did make a secret mission to Lisbon and there almost certainly met Haushofer. Enough to trick Hess into making his desperate May 1941 flight.

But the mission failed from the perspectives of both sides.

Not only did the captive Hess not prove worth debriefing – he was, by then, so out of Hitler’s loop he knew nothing whatsoever of the upcoming invasion of Russia – but Foley concluded him insane.

And Hess had no idea of how Britain was governed or where power lay. It was not, in fact, a land ruled by great Dukes – though there is some evidence he may really have wanted to see the Duke of Kent, the King’s younger brother.

They had, for one thing, met already. The royal family had, then, deep German roots. And outliers, like the disgraced Duke of Windsor – the sometime Edward VIII – had some regard for the Third Reich and Hitler’s achievements.

Kent was handsome, cultured, had a murky past – including a spell of cocaine addiction – and had keenly supported appeasement. He had been friendly with the German Ambassador, enjoyed political chat with German relatives and, with King George VI’s approval, had proposed in July 1939 personally to negotiate with Hitler.

But he never met Hess in Britain and, in August 1942, the Duke of Kent – of whom the Palace has never sanctioned an official biography – would perish in a mysterious plane crash in Sutherland.

The Duke of Hamilton did bitterly say, in later years, that he had “taken all the flak” for Hess, hinting that he had been a scapegoat to spare Royal blushes. But more than this we may never know.

By 2011 Rudolf Hess’s grave was a focus for neo-Nazi adoration and, that July and at the insistence of church authorities, his family surrendered the lease. His coffin and remains were exhumed, cremated and strewn at sea; the tombstone removed and destroyed.

It had borne one cocky epitaph, Ich hab’s gewagt – “I have dared.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © AP/Shutterstock

© AP/Shutterstock © Sipa/Shutterstock

© Sipa/Shutterstock © Shutterstock

© Shutterstock