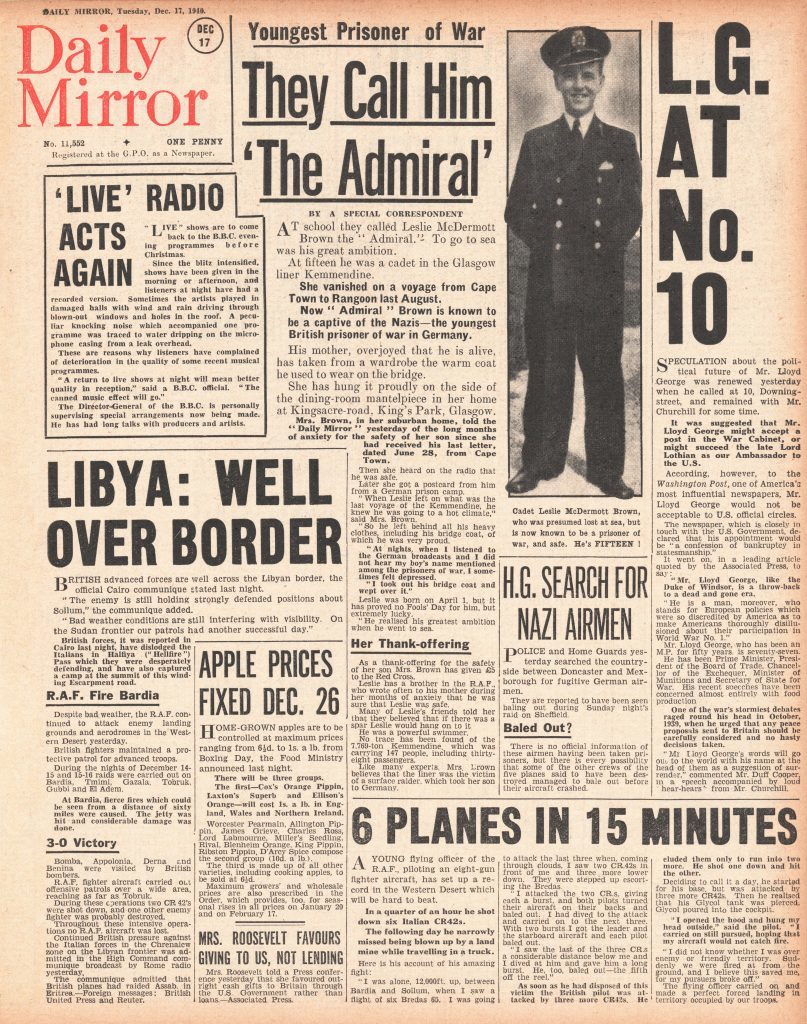

AT school, his longing for the sea saw him nicknamed the admiral.

When war broke out, Leslie McDermott-Brown was too young to sign up but, aged just 15, he still became the youngest prisoner of war.

The teenager was serving as a Merchant Navy cadet when his ship, the S.S. Kemmendine, was sunk by the Germans.

All of the S.S. Kemmendine’s crew were taken prisoner after its sinking in July 1940, and sent to camps in Germany and Poland.

It was the start of five years of captivity for the young seaman.

At the family home in Kings Park, Glasgow, Leslie’s mother Nora was frantic with worry.

She was only to learn that her youngest son was alive and a PoW through one of the infamous broadcasts of the Nazi collaborator, Lord Haw-Haw.

Leslie’s capture made front page news back in Britain and the nation opened its heart and sent letters of support by the sack load to the distraught mum.

Meanwhile Leslie was transferred between four separate camps, where he kept a diary and sent regular letters home.

These are now being made public for the first time in a new book, Captives Of War, by historian Clare Makepeace.

Leslie’s experiences, and those of other British PoWs, give a compelling account of being held for so long behind enemy lines.

Leslie passed away in 1993 but his wartime memories are kept safe by his son, Mark McDermott,

Mark, a psychology professor at the University of East London, said: “Dad’s accounts of life for one of the youngest prisoners reveal the thoughts and courage of a teenager caught up in war.

“Being a PoW more than a thousand miles from home must have been a huge worry for a 15-year-old.

“He would have had to grow up fast in an atmosphere where other prisoners’ emotions and frustrations were never far from the surface.

“However, dad seems to have coped remarkably well. He tended to internalise any feelings of distress.

“It is humbling reading how he learned to cope. I am incredibly proud of him.”

In his diaries, loneliness and a longing for home were masked by cheery stories of how Leslie kept warm in his merchant seaman’s uniform.

Sadly, he had left his warm greatcoat at home as his boat had been destined for Rangoon in tropical Burma, now Myanmar.

In Germany it was so cold one year that he and the other prisoners made ice skates from hut window hinges and played ice hockey on a frozen pond.

Back home his mother Nora, was supported by family and friends.

The single-mum had brought up two sons alone since she and her husband had separated in 1929.

Seeing her boys off to war was to prove a bigger heartbreak.

Her letters to Leslie conveyed love and the reassurance all was well back home.

But, in truth, Nora struggled to hide a heartbreak which had unfolded for the family.

Leslie’s older brother Harley, an RAF gunner and navigator, had been killed when his reconnaissance plane was shot down over the North Sea in 1941. Mark believes the family thought the news would crush his dad.

Leslie was desperate for word from Harley and kept asking why he had not written.

It took some months before Nora was able to bring herself to break the news to her only surviving son.

Leslie spent the next three years in harsh captivity coming to terms with the fact that he would never see his older brother again.

His diary reveals the fighting around the camp that preceded his release. On April 27, 1945, he wrote “All afternoon action just outside the camp. Our troops are advancing….there was a red blaze in the sky.

“Eventually I fell off to sleep. When I woke I was free.”

In the years after the war, while training in the hotel industry in Torquay, Leslie met Valerie Reed and settled in the port of Plymouth. They had three children, Simon, Mark and Antony.

Like many of his comrades, Leslie seldom spoke of his painful years in captivity.

Mark remembers: “Dad wore any legacy of distress lightly and I rarely saw painful memories emerge.

“Despite his Merchant Navy past he never wanted to take us to Navy open days in Plymouth. He hated the fly-pasts.

“I can only assume they would remind him of bombers when he was a PoW.

“One of the great fears in camp was being hit by friendly fire – stray bombs landing on the camps.

“His years as a teenage prisoner had left their mark on him.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe