Joe Biden called Vladimir Putin a war criminal last week. He won’t be the last.

On Thursday, US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken made it clear the United States officially considers that Putin’s invading forces have committed war crimes, referring specifically to the bombing of the Mariupol theatre. He also said the US is working to help document war crimes in Ukraine. These are welcome developments.

Calls for the investigation and eventual prosecution of Putin and those who are conducting his war have grown louder and louder with every report of atrocity coming from Ukraine. But it is necessary to ensure that what politicians, the media, and the commentators mean when they use the term war crime is understood and that the expectations are realistic.

In the last few weeks, the term has been used loosely to describe the mass murder of civilians, the use of forbidden or restricted weapons such as cluster bombs; the potential use of chemical and biological weapons; and the deliberate targeting and destruction of key infrastructure and property that has no apparent military significance.

Hospitals, including maternity units, clinics, and orphanages are targets of deadly Russian shelling and air strikes.

Last week the bombing of a theatre in Mariupol in which hundreds of people, including children, were sheltering, and the bombing of a boarding school lowered even further the depths to which Putin and his military will go. The shelling of a breadline in Chernhiv is reminiscent of attacks on people getting food during the Siege of Sarajevo in 1995, an act for which the people responsible were prosecuted.

The indiscriminate destruction of apartment buildings and whole villages is more evidence of the intent of Putin and his accomplices.

These atrocities are forbidden by the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the Protocols to the conventions adopted in 1977; they are generally referred to as war crimes, but as important, they are also likely to constitute crimes against humanity.

Putin cannot deny he is in command of those carrying out acts that constitute crimes. He cannot escape blame for ordering them, or for knowing they were likely to occur and doing nothing to prevent them, or knowing they have been committed and doing nothing to hold those responsible accountable.

Putin has put his political cronies, military commanders and frontline soldiers in danger of being labelled international outlaws for violating humanitarian law. It is something every one of them must weigh before issuing an order, aiming artillery, dropping a bomb, firing a rocket or artillery shell, or pulling a trigger.

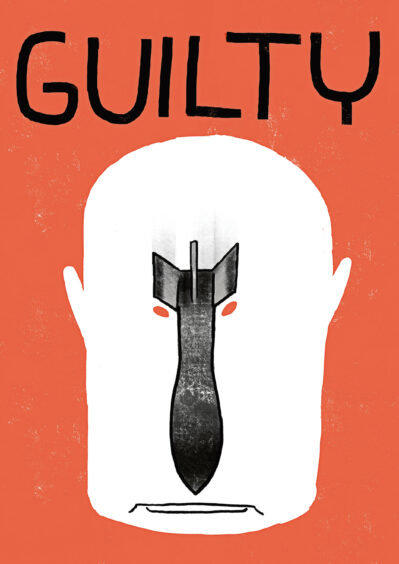

Calls for investigating the crimes Putin and his accomplices are committing imply that they will be prosecuted and punished if found guilty; a not unreasonable expectation, but one that is fraught with challenges and frustrated expectations. It is worth remembering that committing a crime is not always the same as being found guilty of a crime.

In Ukraine, the enforcement of international humanitarian law is facing its biggest challenge since Nuremberg. If it is to preserve its legitimacy, a way must be found to hold Vladimir Putin and his accomplices criminally accountable for what they have done and punish them.

Gordon Brown’s is only one of the many prominent voices calling for Putin to be brought before an international court as was done in Nuremberg. Their sentiment is understandable, but the history is wrong. It is a waste of time and energy to talk about a special international tribunal, like those created to prosecute the surviving Nazi leaders, or to address the crimes committed in the Balkans and in 1994 to deal with the atrocities committed in Rwanda. Nothing suggests Russia, or China, both permanent members of the UN Security Council, would permit anything of the sort for Ukraine.

Meanwhile prosecutions in domestic or hybrid courts created by special laws in Russia, Ukraine, or anywhere else, are not viable given who the potential accused are likely to be.

Regardless of the outcome of the war, Russia is not likely ever to use its own courts to hold Putin or any other Russian accountable.

As for Ukraine prosecuting those responsible, if it comes out of the war with working judicial institutions, it is unlikely to be able to conduct investigations or prosecute those with greatest responsibility for the war even in the unlikely event it acquired personal jurisdiction over them.

Underfunded and understaffed, and lacking as it does the acceptance and backing of the US, the International Criminal Court is the only tribunal available to deal with violations of international humanitarian law on the scale seen in Ukraine.

So will Putin and his accomplices ever find themselves in The Hague?

Perhaps, though not for the crime of aggression. As neither Russia, Belarus or Ukraine are members of the ICC, Putin and his accomplices cannot be tried there on that charge.

There is no such impediment to investigating Putin and his accomplices for violating Article 8, the war crimes provision of the Rome Statute, and Article 7, the crimes against humanity provision. If other limitations built into the Rome Statute don’t prevent it, they could be prosecuted at the ICC for those crimes. In 2015, Ukraine, though not a member of the ICC, formally accepted ICC jurisdiction for such violations committed on its territory.

I have very little doubt the evidence the chief prosecutor is already collecting in his investigation will put Putin and many of his accomplices, including his military commanders and the grunts on the ground, in the frame as war criminals.

And because no statute of limitations will interfere with them being made to answer for their crimes, even if they don’t end up in The Hague any time soon, they will forever live with the possibility they will someday find themselves in the dock.

So, whether the ICC ever prosecutes them for violating international humanitarian law in Ukraine, Putin and his accomplices are war criminals. President Biden gets it, Secretary Blinken gets it, the world gets it.

David Schwendiman was chief prosecutor of the Kosovo Specialist Prosecutor’s Office in The Hague from 2016 to 2018 and has previously prosecuted war crimes in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe