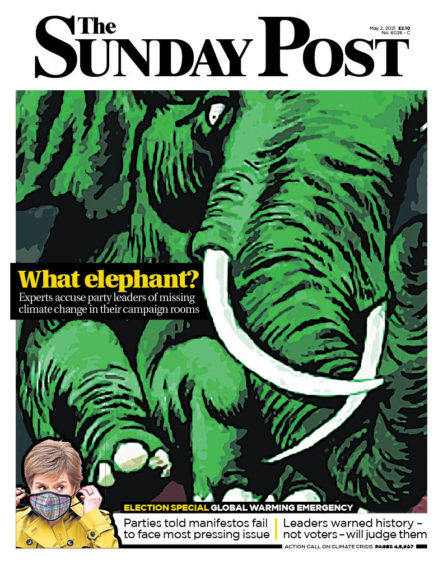

With the Holyrood election a few days away, it is easy to forget there will be an even more important event taking place in Scotland later this year.

Once the dust has settled and questions about what kind of government we will have for the next five years are answered, attention will turn to the landmark United Nations conference on climate change still planned for Glasgow in November.

The Scottish election will determine the future of the 5.4 million people who live here but what is agreed between world leaders on the banks of the Clyde will go a long way to deciding the futures of the 7.9 billion people alive on the Earth today.

This may sound melodramatic but success in Glasgow is critical because each year we avoid cutting emissions adds to the carbon already in the atmosphere and risks passing what are known as climate “tipping points”.

Depending on what we do next, global average temperatures could rise from as little as 1.5C, which the majority of scientists consider to be safe levels, to as much as 5C or more.

Anything above 2C means severe climate disruption for the world economy easily on par with what we have experienced in the Covid-19 pandemic. Higher still and it is estimated that significant parts of the globe will be unable to sustain life as normal as we move through the century.

Governments have already made some commitments to reducing carbon emissions and, on the present trajectory, we are on track for between 2.5 and three degrees of warming. This is still enough to have severe implications for countries around the world, including Scotland.

Even at current warming of about one degree above pre-industrial levels, Scotland is beginning to experience climate shocks such as the freak rainstorms that led to the destruction of parts of the Edinburgh-Glasgow and Aberdeen-Dundee rail lines last year, or the heavy snowfalls caused by fluctuations in the Arctic that hit Scotland this February and March. These kinds of events will only become more regular in the coming decades.

Scotland is a fitting backdrop for the UN meeting because the nation has some of the best preconditions on Earth for becoming carbon-neutral; plentiful wind and water, heavy engineering skills and relative wealth.

When imagining what a climate-friendly future might look like, Scotland has the potential to be a template. We produce most of our electricity from renewables after an explosion in wind power over the past decade and are set to be a net exporter of renewable energy in the near future. We can also manufacture climate-friendly hydrogen fuel from wind that can power trains and ships.

Look deeper, however, and it is clear Scotland still has a long way to go. Decades of road-building mean that many journeys in Scotland are still faster and cheaper by car than by public transport.

Buses can remain inconvenient and expensive, and cycling is still a minority pursuit. Since 2008 the number of vehicles registered in Scotland has actually increased by more than 10%. Emissions from cars, road freight and aviation collectively have all gone up, according to official figures.

All the renewable energy being generated is not reaching our homes or changing the way we move around, meaning Scotland is still a significant source of carbon emissions, even while we have renewable electricity to spare.

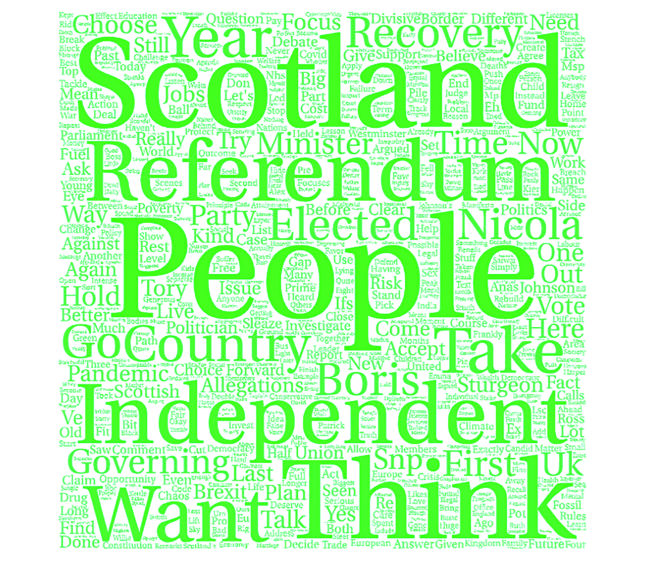

What this means for the average Scot is obvious: We need to change the way we live and move, how we heat our homes, and how we manage our energy consumption. There is no ambiguity about the science but politically it is a hard sell. The five main Holyrood parties are making different offers to voters, mixing uncomfortable truths with promises of business as usual.

All the parties are bound by the Scottish Parliament’s decision to pass binding targets as part of the Scottish Climate Change Act, which demands a 75% cut in emissions by 2030. So far the Scottish Government has repeatedly failed to meet those targets. Scotland is also in a quandary because of its reliance on the oil industry. Climate models show we can not burn all of Scotland’s oil reserves and stay under the crucial two-degree target globally.

The SNP has been keen to stress its green credentials with the world’s eyes on Glasgow but has made more noise about recovery from Covid and an independence referendum than the climate. This is partly because the economy and recovery are higher on the list of priorities for voters but also due to the party’s complex relationship with the oil industry.

Nicola Sturgeon’s party is less enthusiastic about oil and gas than has previously been the case, and there is a commitment to use oil and gas revenues in an independent Scotland to fund decarbonisation and guarantee the long-term economic future of the north-east. Gone, too, is the enthusiasm for controversial fracking for shale oil on land yet the party still maintains that fossil fuels are “an important part of the energy mix”.

As the biggest party, it is perhaps no surprise the SNP wants to be all things to all people, promising decarbonisation and social justice on the one hand whilst not frightening off their supporters in the north-east who are reliant on oil. This means a lot of cans have been kicked down the road.

What the SNP is offering on climate change is essentially more of the same. There will be further expansion of renewable energy, broader commitments to encouraging electric vehicles, and a home decarbonisation programme to help people dump their gas boilers and oil heaters for electric. The details, however, are vague and the message is one of evolution, not revolution.

The Scottish Conservatives have moved away from the green branding that was so prominent under David Cameron and Ruth Davidson but the Tory manifesto contains important commitments to emissions reduction. The party is committed to using Scotland’s forests and peatlands as a carbon sink, but the Tories are still opposed to land reform and the breaking up of large sporting estates that would allow this kind of restoration.

They are also bullish on oil, saying they “believe that North Sea oil and gas has a long future of many decades ahead, with petrochemicals continuing to be used in the plastics, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals we use every day”.

The way statistics are assembled means Scotland’s oil and gas is not included in its climate calculations because it is burned elsewhere. Although the Tories are correct in saying some North Sea oil is used for plastics and medicines, a significant chunk of it still makes it into the world’s cars, trucks and heating systems.

The party is also in favour of expanding the M8 motorway to three lanes all the way from Edinburgh to Glasgow, despite suggestions that this will merely lead to furthercongestion and increased emissions.

Elsewhere, there are some warm words on farming and sustainability but Scottish Conservative leader Douglas Ross is yet to fully explain how his sums add up, especially as he has also promised tax cuts for higher earners, which would reduce the amount of money available to invest across the board.

Labour is trying to play down the constitutional question in favour of its bread-and-butter issues and has put climate, economic recovery and social justice at the heart of its manifesto pledges. Anas Sarwar has declared climate recovery a “national mission” to help Scotland reach net-zero emissions in 25 years. Labour also says that it wants to use the climate talks to make Glasgow synonymous with bold and ambitious action to tackle the climate emergency.

Part of this is a green jobs recovery plan and commitments to create a publicly owned energy provider that can reduce costs to the average household, tackle fuel poverty and put profits back into sustainable energy.

Labour may be a long way from power, but it seems intent on providing robust opposition to the SNP on climate change. If Anas Sarwar has a good election then the Scottish Government will find itself under pressure on its climate commitments from both Labour and the Scottish Greens.

Unsurprisingly, the Greens have gone hard on climate change in this election. They see an appetite from young people, in particular for more radical action.

The Greens – whose co-convener Lorna Slater is a renewables engineer – are pushing what they call a Green New Deal. This means not just cutting emissions but using carbon reduction and green economic levers to rebuild the economy after Covid and pull people out of poverty.

By far the most radical of all the manifestos, this is tied to other measures such as land reform and increased taxes on polluters. As co-leader Patrick Harvie said last week, the Greens want to use climate investments and Covid recovery to create a significantly different society. They also want to spend £22bn over the next 20 years on rail alone and say their vision is the only one capable of securing the 75% reduction by 2030 mandated by the Scottish Climate Change Act.

The Liberal Democrats were once the default choice for green-minded voters and the party’s manifesto contains some interesting promises, from home heating grants to grass roofs.

The party has come out in opposition to low-traffic neighbourhoods that encourage walking and improve safety for children and the elderly but, like the Greens, they want to introduce a levy on frequent flyers, who are some of the highest carbon emitters in the country.

Whatever the result this week, climate change is not going away. For two weeks in November the world will be watching Scotland, a country that helped kick-start the industrial revolution and has a love affair with fossil fuels. All the parties must now answer the question of how Scotland can kick-start a green revolution instead, and make Glasgow a turning point for all of us.

Dominic Hinde is an environmental journalist and lecturer in sociology at the University of Glasgow.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Sebastian Grote/AWI via ZUMA Wir

© Sebastian Grote/AWI via ZUMA Wir

© SYSTEM

© SYSTEM