For almost as long as men had tried to fly, they had dreamed of taking off from water.

The French had an awful lot to do with the earliest days of conventional flight and they were also at the very birth of seaplanes.

Alphonse Penaud, who in the 1800s advanced theories about wing shapes, airplanes, helicopters and the like, would also file the first patent for a flying machine with a boat hull beneath it.

This was in 1876 and several attempts and near-disasters would occur before March 28 1910.

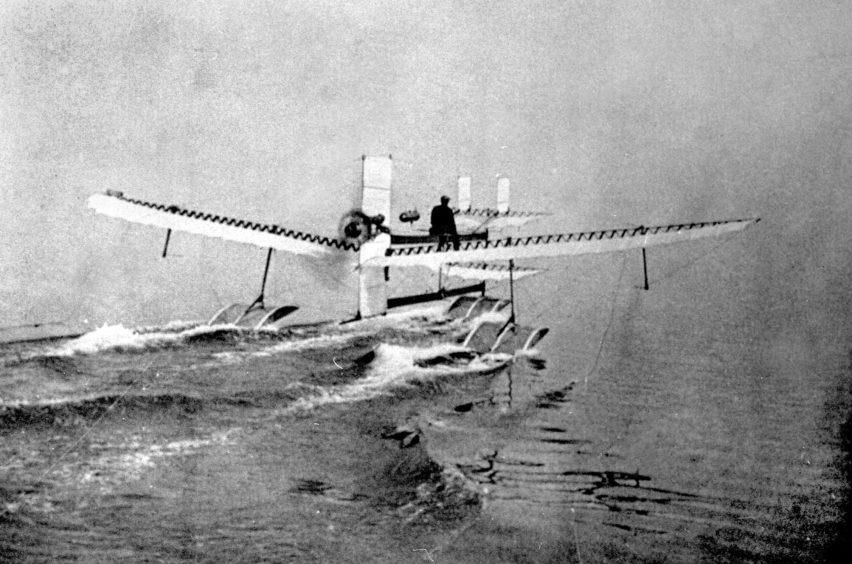

On that date, another Frenchman, Henri Fabre, flew the first successful powered seaplane and aviation history entered a thrilling new phase.

He did so in the Gnome Omega-powered hydravion, a trimaran floatplane, and his feat inspired many others who later relied on Fabre’s designs for similar machines of their own.

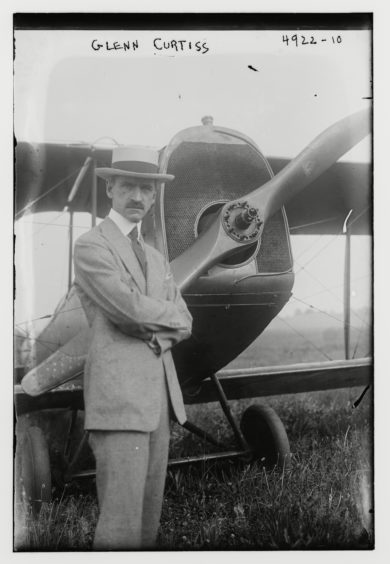

In just two years, Monaco hosted the first hydro-airplane competition, with Fabre’s inventions up against machines from other big names of the time such as Glenn Curtiss, an American, his compatriot Alphonse Tellier and Anglo-French aviator Henry Farman.

That same year, 1912, the first day of August saw the very first scheduled seaplane passenger flight, from Aix-les-Bains in France’s south-east Savoie department.

The five-seater was such a success that the French Navy ordered its first floating plane the same year. Suddenly, everyone who was anyone had to have the latest thing, a plane that could take off from water rather than dry land.

Just weeks after Fabre’s breakthrough, American Glenn L. Martin had set time and distance records after flying his homemade seaplane in California, but Fabre had been first and would always be the name in the history books.

That’s not to take anything away from Gabriel Voisin, who five years previously had landed his towed kite glider with floats on the River Seine, but Fabre’s feat was amazing for its time.

Even today, while the majority of us have been on a passenger plane, few have had the unique thrill of taking off from or landing on water in a seaplane.

Britain, however, was not terribly far behind our Gallic cousins in the race to fly from a watery take-off.

English duo Captain Edward Wakefield and Oscar Gnosspelius had used England’s largest lake at Windermere to test the feasibility of flight from water in 1908.

Large crowds got very excited but ultimately deflated as each attempt geared up but then failed to see their craft rise to the skies.

When they eventually ordered a machine like Fabre’s, it did take off, in 1911, although it soon crashed into the lake again.

With a more helpful wind, though, subsequent flights did much better and they got to 50 feet before making a nice turn and a perfect landing on the watery surface.

The crowds were beside themselves with excitement, as were the men behind the whole thing – seaplanes were going to be much more than a flash in the pan.

By the time of the Balkan Wars in 1913, inevitably, seaplanes were being used to hurt, rather than entertain, the folks below. A Greek seaplane bombed the Turkish fleet.

In the months before the Great War, J Samuel White, of Cowes, Isle of Wight, had built a flying boat.

Also in 1913, there was a collaboration between SE Saunders’ boatyard in East Cowes and the Sopwith Aviation Company, which produced the so-called Bat Boat, a plane with a laminated hull that could work on water or dry land.

Today, they are known as amphibious aircraft and it was the very first completely British airplane to make six return flights over five miles inside five hours.

Although designers were still struggling to make properly efficient, reliable seaplanes well into the war years, the Royal Navy did get F2, F3 and F5 flying boats in time to use them for patrols and searches for U-boats.

By 1918, they could be towed on lighters, a type of barge, as close as possible to Germany’s northern ports before taking off.

This extended their range immensely and some Navy seaplanes engaged with German seaplanes and in the summer of 1918 shot several out of the skies.

Their effectiveness had been so impressive that top brass decided to use them in this way as much as possible. Dazzle-painting was introduced, which was a method in which the planes were hard to spot when they were onboard ships or barges, and the Navy tried to take as many as possible as close to Germany as they could get.

In the Second World War, these magnificent machines proved just as effective and the battleship Bismarck was located by a Catalina from Lough Erne in Northern Ireland.

The war’s largest flying boat, however, belonged to the other side.

The Blohm & Voss BV 238 was the heaviest aircraft ever built when it first flew in 1944.

In 1990, Tom Casey took the whole thing to new levels. He flew more than 29,000 miles in 188 days, landing only on water for the first floating plane round-the-world flight.

Many places he visited had never seen planes that could land on water and therefore lacked bases to tell him about weather conditions, but he survived and made history.

These days, most such planes are amphibious and can land on water or dry land. But they continue to thrill us.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Photo by Branger/Shutterstock

© Photo by Branger/Shutterstock  © Photo by Nara Archives/Shutterstock

© Photo by Nara Archives/Shutterstock  © Photo by Nara Archives/Shutterstock

© Photo by Nara Archives/Shutterstock