With a 76-year gap between Fred Perry and Andy Murray’s Grand Slam triumphs, British tennis is often seen as lagging behind the rest of the world – but history suggests that may not be the case.

Author Kevin Jefferys tells Alice Hinds the Honest Truth about the sport in the UK.

What made you decide to research the history of British tennis?

I’ve always loved sport since I was a youngster, particularly football, cricket and tennis, and I’ve played tennis – to a modest club standard – throughout my life.

During my career as a history lecturer, I developed a growing interest in sport history so, since retirement from academia, it seemed a natural step for me to focus on tennis.

Is the British contribution to the sport often undervalued?

Many of us growing up are familiar with British tennis players under-performing at Wimbledon, but the broad argument of my book is that if you look at the historical record in world tennis as a whole we’ve fared better than we often think.

The men’s singles title at Wimbledon remains a hugely coveted prize, but this should not be the sole criteria for assessing national performance.

The wider record shows barren spells alternated with strong periods yet, overall, British players have enjoyed considerable success when credit is given to achievements beyond the men’s title in SW19, including the three other grand slam tournaments in the global tennis calendar, women stars of the game, the Davis Cup, and the recent innovation of wheelchair tennis. The USA is the highest achiever in lawn tennis history; but Britain is far from an also-ran in the sport.

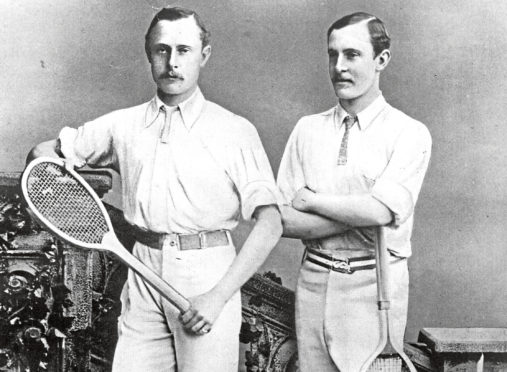

The successes of players, dating from the Renshaw brothers in the Victorian period to Andy and Jamie Murray more recently, compare favourably with the national record in other major sports.

How can sphairistikè be understood as an early version of lawn tennis?

Lawn tennis was invented in the Victorian period and much of the credit goes to Walter Clopton Wingfield, a retired British Army officer who served in India and China.

Hoping to bolster his income in retirement, Major Wingfield devised a garden party pursuit that he hoped would appeal to wealthy friends, ladies and gentlemen.

In 1874 he patented a portable set of equipment that included four rackets, balls, a net and net-posts, calling his new game Sphairistikè, from the Greek for “ball-play”.

Within a year or so, more than 1,000 boxes were sold, priced at £10 or 5 guineas for large and small sets respectively; clients included members of the royal family and the upper echelons of the aristocracy.

Lawn tennis, at the outset a fashionable and genteel summer activity for the English leisured classes, was born.

How did the Second World War impact British tennis?

Competitive tennis largely ground to a halt for the duration of the conflict, with many clubs in Britain, including the All England in the grounds of Wimbledon, offering their land for military use, sometimes even for the growing of crops. The drastic reduction in playing opportunities meant there was no ready-and-available talent pool to draw from when peace returned in 1945.

By contrast, some measure of normality was maintained in other combatant states such as the United States and Australia, paving the way for the nations to forge ahead as tennis superpowers.

Who is your favourite tennis player from history?

I’ve always preferred watching players who have all-round court skills and subtlety in their game, so among my favourites past and present in the world game I’d include John McEnroe (despite the tantrums), Justine Henin and Roger Federer.

And then, of course, there’s Andy Murray. I was lucky enough to be in the crowd when he made his Centre Court debut as an 18-year-old in 2005, losing a tight five-setter in the third round, and it was clear even then he was a special talent.

British Tennis: From the Renshaws to the Murrays, £18.99, is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe