She never showed her face as Still Game’s Meena. But that was not the only thing sitcom star Shamshad Akhtar was shielding from fans.

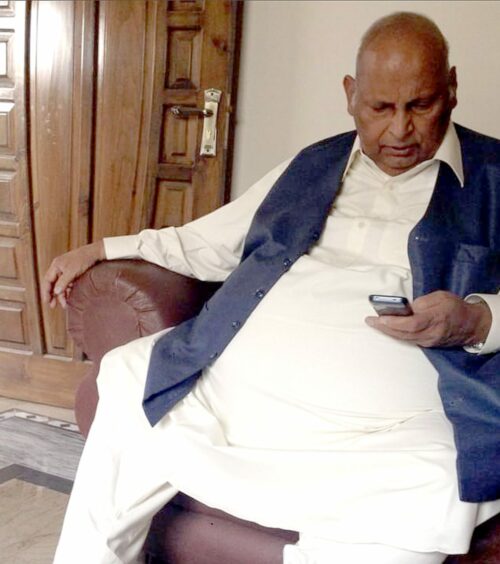

The Pakistan-born actress for years concealed the shocking secret that she was a victim of domestic abuse, and had suffered decades of rape and beatings at the hands of her cruel husband, Abdul Ghani.

The actress, now 73, can finally speak out after Ghani died last year. She said: “I could not tell anyone. Not even my children. I had married a wicked man who beat me, punched and kicked me. But my children were innocents.

“They were my whole world and I did not want them to suffer. I took the beatings, the unwanted sex, the punches and his hands around my neck. I covered up the marks Abdul left on me because I did not want to disrupt my children’s lives.

“If I had spoken out, he knew they were my whole world and he would have taken them from me.”

Trapped

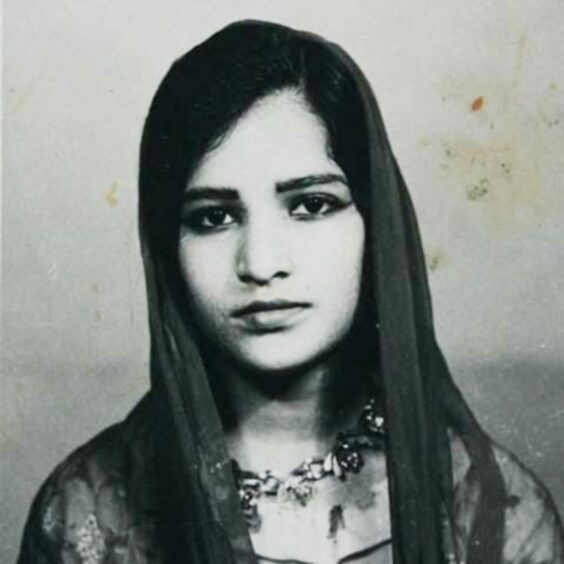

Shamshad was just 15 when she became trapped in an arranged marriage in Lahore to a much older man whom she had never met before. She said: “I grew up in a very happy home where I never saw violence. My parents loved each other and, as my mother had lost two sons before she had me, I was a treasured daughter. I grew up as a bit of a tomboy and at school I always loved drama.

“My parents did not want me to marry but at that time they were blackmailed into it. Abdul and his uncle told my family that they would tell everyone I was a bad girl if they did not agree to the marriage.

“In my culture that would have meant that I would never marry and my family would suffer disgrace. So I had to marry a man I did not know or like.”

Abdul was determined to bring his young wife to the UK, where he got a job as a bus driver in Glasgow. Shamshad said: “I was still just 15 and I would not have been legally able to come to Scotland as a wife so he changed the dates on my passport so I could enter the country. I was brought here after just 20 days of marriage. I was trapped, locked in a single room all day because he did not want me speaking to the neighbours about the beatings and the things he did to me. I could not even speak the language anyway, so it would have been hard for me to tell anyone.

“All I could do was watch people going by from the window of my locked room in a tiny flat in St Vincent Street in Glasgow.

“My first words of English were learned from the fruit seller who sold from a barrow under my window. I could hear him talking and shouting out what he had.

“My first words were ‘one and a tanner’ but I could not find the word tanner in the dictionary. It was a long time before I learned what a tanner was. I did not even know what hello meant.”

Shamshad’s prisoner-like existence went on for years, interspersed by beatings. She said: “As soon as we married, he started hitting me. It was a huge shock to me because I had never experienced anything like that in my life. It soon became a way of life. I’d get hit if I spoke. I’d get hit if I did not speak. I was still just 15 years old. It was not long before I suffered a bad breakdown. I became pregnant and lost the baby. I felt alone and so far away from my family. I had no one.”

Shamshad was determined not to worry her family back in Lahore, so she did not tell them about the violence and cruelty she was suffering.

Her mother’s letters, delivered every two months, were the only ray of sunshine amid the cruel darkness.

But even then, Abdul’s controlling streak and vicious temper was such that he would not even allow Shamshad to write back.

She said: “He even controlled what I was allowed to write back to my mother. He would stand over me and make me write that everything was good. That I was happy. I could not tell my family the truth, that I was a prisoner in my own home and that I was beaten and abused every day. I had nobody to turn to.

“Even his friends who came over with their wives to watch the movies which came from home, I was not allowed to talk to them.

“My husband would hit me and tell me to say that I did not want to see the film. I loved seeing the films because they reminded me of home but Abdul did not want me talking to anyone for fear I would tell what he was doing.”

Finding love

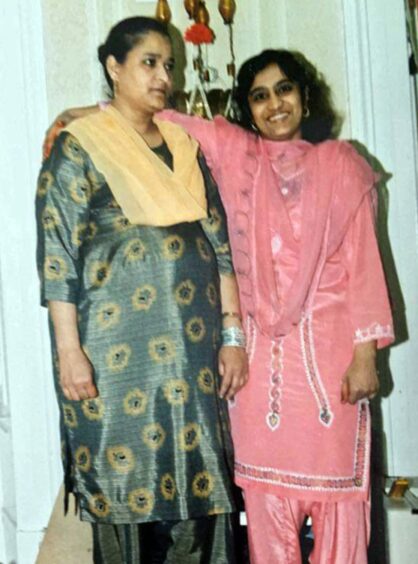

Shamshad did eventually find love in her life with the birth of her daughter Sofia, now 55, and then her two sons Moshin, now 53, and Anjum, now 47. But she was heartbroken after losing another son and a daughter to ill health. She said: “My children are everything to me. I put all my love into them and they are so precious.”

When the children arrived, Shamshad was allowed a black-and-white television. She said: “I finally learned to speak English from watching children’s television. It meant I was no longer unable to speak to others and it brought a freedom to my life.”

As the children grew, the family had several shops, first in Bishopbriggs and then in Crow Road, Glasgow.

Shamshad would wake at 5am to get the shop ready for early-morning customers before taking her children to school. She said: “It was a hard life, working all the hours. But I did it because I wanted to make sure my children had the best in life. No matter what I did or how hard I worked, I was still beaten most nights. He would wait until after midnight so the children were sleeping before he would attack me, punching me and kicking me.”

Things came to a head one night 20 years ago when the nightly beating took a deeply sinister turn.

Shamshad said: “Most nights he would just hit me and I could cover up any marks he left. But this one night was different. I could see in his face and by what he told me, that this was my last night on earth, that he meant to kill me. This was the night he planned to kill me.

“He grabbed me by the hair and threw me violently to the floor, standing on my thighs so I could not move. Then he grabbed my nose and covered my mouth, blocking off my airways.

“I could not breathe. My eyes were bulging out as I tried to struggle against his heavy weight on top of me. He was so very strong, I thought that was it. I would die on that floor. But then I felt his finger go into my mouth and I bit down as hard as I could, hanging on for dear life as he screamed obscenities at me. Somehow, I managed to scream out, and my eldest son came running to punch him off me.

“Abdul flew back at him, kicking him like a football and smashing him off walls in his fury. But my boy had saved my life.

“As I escaped into the close of our flat, I realised how lucky I had been. I was supposed to die that night.

“I vowed that I would never let Abdul touch me again. I fled and never returned. I had nothing except the clothes I stood up in but I was alive and I would not let any man ever hit me again.”

Shamshad was by then in her 50s and, despite all her hard work, had to start all over again. She said: “My husband took everything. He claimed he owed so much money, there was nothing left in our businesses to give to me. It was a lie but there was nothing I could do.”

Freedom

Once removed from the trauma of her old life, Shamshad found a freedom finally to be herself, campaigning to get justice for Surjit Singh Chhokar, 32, who was stabbed to death in Wishaw in 1998.

Shamshad was by the side of his family when they saw Ronnie Coulter jailed for the horrific murder after two previous trials that ended without a guilty verdict.

Her love of drama paid off when she was asked by actor and comedian Sanjeev Kohli, a family friend, to take part in a comedy drama about a late-night bus. She was subsequently asked by director Ken Loach to take a role in his acclaimed film, Ae Fond Kiss.

Kohli, 51, went on to play Still Game’s Navid Harrid, whose shop in Craiglang was the scene of many of the sitcom’s most hilarious moments. As the shopkeeper’s wife, Meena, Shamshad’s face was not shown on screen until the final episode of the Glasgow-set comedy in 2019.

Shamshad said: “My first role introduced me to the Comedy Unit, and when they were casting Still Game, I got the role of Meena. I loved it. Meena never showed her face. But she ruled the roost and her quick put-downs were the best.

“It was such fun playing Sanjeev’s wife. I’m old enough to be his mamma… in fact he often calls me mum when he comes to see me still. We had so much fun while doing Still Game it took away all my sadness and I was able to laugh again. I got to show my face in the last episode, and now everybody calls me Meena instead of Shamshad.”

She shared details of the abuse she suffered with Still Game pals including Kohli and Jane McCarry, who played Isa, and they have continued to support her.

She said: “I have never spoken about it in public. Abdul died last year, so I am free to speak now. There may be other women who have suffered what I went through, older women. The young ones wouldn’t put up with what we did. These things should never have happened to us. We should not have to carry them with us.”

Marsha Scott, Scottish Women’s Aid chief executive, said: “Shamshad Akhtar’s story and courage in speaking out is so inspiring. It reminds us both of the sacrifice and resilience demonstrated by so many survivors of domestic abuse but also of all the ways our systems fail girls and women.”

Call the Scottish Women’s Aid helpline on 0800 027 1234 or Rape Crisis Scotland on 08088 010302

Star’s bravery inspires new short films by celeb pals

Shamshad Akhtar’s bravery has inspire her celebrity friends to create a new short film series.

Still Game actress Jane McCarry and Mrs Brown’s Boys star Gary Hollywood have produced Mind That Time, which gives the pals a chance to interview ordinary people with extraordinary lives.

Developed for online streaming, the series features chats with everyone from Shamshad to a real-life dominatrix. Jane said: “I’m not too far from Isa, you could say. I truly am a nosey… you know what!

“I love a good gossip with my pals, and so does Gary. We thought we were the perfect match to do this, and who better to interview than ordinary people who really do have extraordinary lives.

“I’ve always loved going round to Gary’s mum’s house to listen to her and her pals talking about the things they used to get up to when they were office cleaners. The stories were hilarious. You simply could not make them up. That’s when we decided to make the show. Far too many of the older generation are fading away, and with them go all the fabulous stories of the past.”

Gary said: “Me and Jane have always loved a right gas, and so many of the funniest stories are started off by one of us saying, ‘Mind that time…?’

“That’s why we thought it was a perfect title. The lives of ordinary people are absolutely fascinating. They have incredibly powerful stories to tell.

“Jane and I are incredibly proud of our culture and where we came from, and this is a wonderful way of celebrating that and the people who make Scotland what it is.”

Jane said: “I’ve loved Shamshad for years, I’m proud she has shared some of her incredibly important story with us. What happened to her was something that happened to a lot of other women who never had a voice to speak out.”

Mind That Time launches tonight on YouTube

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Jamie Williamson

© Jamie Williamson © BBC/Alan Peebles

© BBC/Alan Peebles © Jamie Williamson

© Jamie Williamson