In a career spanning decades, Silvio Berlusconi has assumed multiple roles – property entrepreneur, Prime Minister of Italy (three times), media magnate and disgraced host of some the most notorious parties since Caligula.

After many commentators had written him off when he was buried in an avalanche of sex and sleaze scandals, however, could the billionaire 85 year old be on the verge of an astonishing comeback as Italian President, a post traditionally reserved for establishment figures of unimpeachable character?

A month before the presidential election, Berlusconi has launched an unorthodox backdoor campaign, lobbying MPs with characteristic scorn for convention and, because of a particular conundrum facing Italy’s political class, Berlusconi could possibly pull off a jaw-dropping return to public life.

While dominating Italian politics and media for two decades, the media mogul became notorious for his sexist, racist remarks on the world stage, boasting of using his “playboy” tactics on Finland’s president, complimenting Barack Obama on his “sun tan”, and comparing a German MEP to a concentration camp guard.

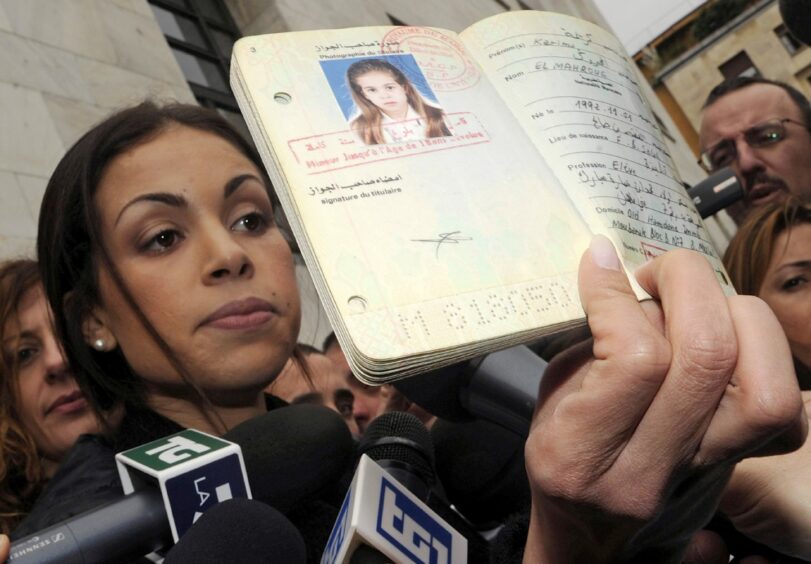

When the “bunga bunga” sex party scandal emerged in 2010, witnesses described orgies at his villa outside Milan where prostitutes filled the guest list before he was charged and convicted of paying a 17-year-old woman for sex. The conviction was overturned on appeal.

While prime minister he used his powers to tighten his stranglehold on Italian media but was still widely derided for mismanagement of Italy’s economy, and for introducing numerous laws to protect himself from prosecution and benefit his business interests.

His leadership ended in humiliation in 2011 when he was forced to hand over the premiership to technocrat Mario Monti amid a surging national debt crisis and fears that Italy could default on international loans, harming its credit rating.

Since then Berlusconi has faced ongoing legal woes. He may have been acquitted of the charge of sex with underage nightclub dancer Karima el-Mahroug but a prosecution for allegedly corrupting witnesses continues, delayed by bouts of ill-health which frequently coincide with court hearings. He was convicted of tax fraud in 2014, which saw him temporarily banned from public office. Unfazed, he used the community service time in an old people’s home to win over potential voters with Frank Sinatra sing-alongs.

His political prospects brightened when the ban on public office was lifted in time for him to win a seat at the 2019 European Parliament elections. Last year he moved closer to full rehabilitation when his party joined the grand coalition led by the former president of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, a stalwart of the European institutions.

Pollsters place Berlusconi second in the race, with 12% of the general public backing him as Italy’s new president, when the incumbent Sergio Mattarella’s term ends in February 2022. However it’s not the public he needs to win over. The president is elected by more than 1,000 parliamentarians and regional representatives.

While there are no official candidates, Berlusconi has indicated that he is available to serve the country once again, sending flyers to voting MPs.

Ahead of Berlusconi with 17% of the popular vote and the bookie’s favourite is current premier Draghi, whose establishment credentials have helped Italy’s stock rise over the past year, with the economy growing more than 6%. Draghi also enjoys approval ratings of 65%.

But with the Omicron variant circulating, and structural reforms to be implemented to guarantee receipt of EU reconstruction funds, Draghi is coming under pressure from banks, industry and political leaders to stay put as prime minister.

The often-fractious grand coalition government, which spans the political spectrum could fall apart without Draghi’s clout, so Italy’s political classes are hunting for an alternative president, to keep Draghi in the prime ministerial harness until elections in 2023. Berlusconi could be the beneficiary of this uncertainty.

He remains a political player, leader of Forza Italia, the political party he formed in 1992, and a powerful dealmaker behind the scenes. Voters in Italy are less outraged by sex scandals than elsewhere.

And on the international stage, European leaders have increasingly recognised that despite his outrageous remarks, Berlusconi’s unfaltering pro-EU position makes him a useful ally to counter the surge of nationalist and populist sentiment in Italy and in the European Parliament. If nothing else, a Berlusconi presidency would guarantee a positive Italian attitude towards the European project and Nato, even if a right-wing government wins the next election. Berlusconi is backed by his allies in the right-wing coalition in Italy, but he is unlikely to have the numbers needed for a majority.

Instead, he hopes to benefit from the many MPs who want to at all costs avoid early elections which would be a premature finish to their lucrative parliamentary salaries – the Italian parliament is to be downsized after the next election which, along with swings in the polls means that two out of three parliamentarians might not come back after elections.

“An Italy with Berlusconi as president of the republic and Draghi as prime minister would be a leading country in Europe and internationally,” said Roberto Occhiuto, president of the Calabria region and member of Berlusconi’s party. “I am convinced that many in parliament who would not admit it even under torture would vote for him.”

Pollster Lorenzo Pregliasco, of You Trend, said that the presence of a huge group of independents and a secret ballot means that the result was uncertain. “There is some room for surprise, roughly 100 people with no allegiance and a secret ballot, makes it hard to predict the behaviour of MPs.”

He said Berlusconi would likely get votes in early rounds, when there is a higher threshold of a super majority so people feel unbound by implications of the vote. “If his allies support him he could get up to 450 votes. Should we see more than that it would be a sign that he is able to draw support from unpredictable sources.”

Political reasons aside, his age and health condition, considered to be quite frail, could hinder his chances. Pregliasco said: “He has very little chance of becoming Italy’s president.”

While allies are pushing hard to present Berlusconi as a moderate and a political grandee, for others he remains deeply divisive, held at least partly responsible for Italy’s reduced status on the international stage, and yesterday’s man. Michael Day, author of Being Berlusconi: The Rise And Fall From Bunga Bunga To Cosa Nostra, said: “In this period of great political uncertainty, Italy needs as its head of state a figure who is well known, and also someone who is not a sleazy crook or an international laughing stock. Berlusconi probably ticks one of those boxes.

“If he was appointed president, the press would have a field day but I can’t imagine it would help Italy’s ambitions of stepping up with France and Germany to be part of the leading power bloc in the post-Brexit, post-Merkel Europe.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe