Simon Lammy dreamed of being a doctor from the age of four. Hearing about Ben Carson, who overcame racism to become one of the United States’ most acclaimed doctors, cemented his ambition five years later.

It would be fair to say, however, his teachers did not share his dream or support his ambition.

“The atmosphere at school was not conducive to thriving,” he says, with dry understatement.

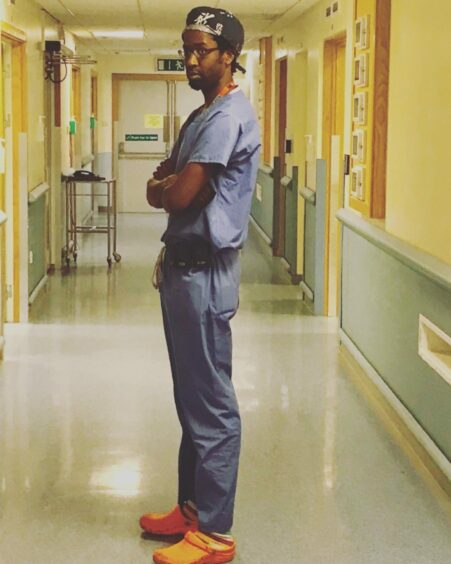

Today, a brain surgeon, a grade-eight surgical registrar at the Institute of Neurological Sciences in Glasgow’s Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, he is speaking of how he endured and defied the patronising racism of teachers to secure his ambition in the hope of inspiring others from backgrounds like his own.

“I was not going to be put off, no matter how often the teachers at my comprehensive school told me I was not bright enough. Let’s say, it was extremely challenging to push myself there.

“Looking back, I despair of any teacher who tells a child they are not capable of achieving their ambitions, irrespective of race, class and gender. I survived school thanks to my parents. My upbringing expects me to use my skills to help and encourage others to achieve. I want to inspire and encourage children from all backgrounds to reach their best because so many do not.”

Now age 40, as a Royal College of Surgeons of England surgical trainer, book author and publisher of more than 40 research papers and an ambition to be an academic neurosurgeon, he can look back with dismay not anger.

“Some teachers were crushing in their put-downs,” he said. “And, as one of only a handful of black pupils in my year, terrible things were said to discourage me. It crushed my confidence, as it must have done to so many other children of ethnic or minority backgrounds and so I kept quiet.

“At home my parents encouraged me to focus on hard work with a determination to achieve. That meant working three times as hard as anyone else and reading twice as many books.

“It also meant learning a lot about English history, the country of my birth, to ensure no one could say I didn’t belong here. That, and passing my grade eight piano as a teenager, as taught by my Church pianist.

“Work three times as much and be twice as smart if you can was the rule. The Caribbean saying about the hand that rocks the cradle rules the world was the ethos fostered by two hard-working immigrant parents from the West Indies desperately keen for their children to achieve their potential. My parents knew not to rely on the school to educate their sons.”

The facts:

- 2% of students at Scots medical schools come from the country’s poorest postcodes.

- 32% come from the wealthiest, according to 2016 research.

- 63% came from the three most affluent neighbourhoods in Scotland.

- 8% came from the poorest three neighbourhoods in Scotland.

- 26% of Scots medical students went to private schools.

- 4% of children in Scotland attend a private school.

Church, family and school were the pillars of his childhood and of others focusing on overcoming prejudice. He was brought up in Essex as a Seventh Day Adventist, a church his parents attended every Sabbath with their children where, he says, he flourished memorising Psalm 23 as a five-year-old, never to be forgotten.

“Church proved to be the place to be continually inspired because there racism didn’t exist,” he adds.

Getting into and through his medical studies, where there were more privately educated and middle-class students than not, presented fresh challenges. He did a neuroscience degree at University College, London, (UCL) where he was the only working-class student in his year. The confidence of aspirational middle-class students shocked and fazed him.

“Being from what felt like very humble beginnings I worried about asking questions in lectures for fear of sounding culturally uneducated and missed so many chances to engage with lecturers.

“But I felt at home at UCL, a much more positive experience than at school, and thrived in one-on-one exchanges with academics where my confidence grew.”

A degree in neuroscience helped him gain entrance to UCL’s medical school, which he describes as his dream. “No one knew it at the time,” he said, “but I used to find it difficult to articulate myself and my heart would race if talking to these distinguished educators. The shame narrative of my humble beginnings was paralysing at times.

“To gain confidence I ran for election to be student union president, which forced me to come out of my shell and argue my position on often controversial issues. It was a bewildering experience but I was president twice and learned a lot. These extra-curricular pursuits are integral to building a CV.”

The surgeon, who has worked in Scotland since 2010, is now on a mission to inspire children from deprived areas to achieve their potential. His Glasgow neurosurgical unit is one of the busiest in the UK, with the west of Scotland’s alcohol problem having a higher number of trauma patients than other areas of the UK.

Working with the consequences of the health and social problems impacting Scotland’s poorest postcodes, makes him even more determined to encourage the children growing up there.

“Some families live in a perpetual storm with lives so difficult that you want to weep for them after you leave the hospital. Many health care professionals experience this and accept it is part of the job, so you must use your training to help your patients in any way you can.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley