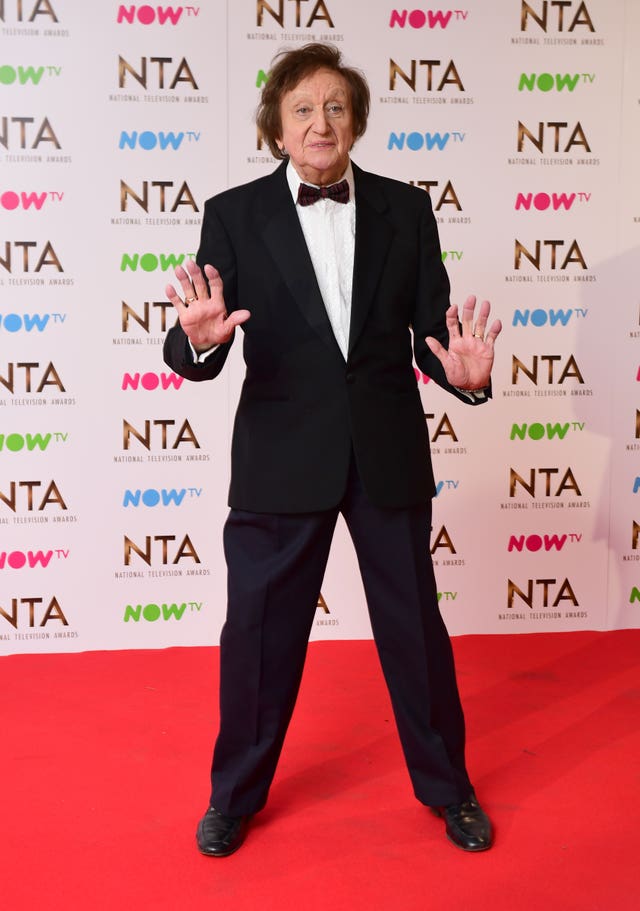

SIR Ken Dodd, master of tickling sticks, Diddy Men and tattifilarious comedy, reduced fans to helplessness with his bucktoothed grin, a shake of the through-a-hedge-backwards hair and a cry of “How tickled I am”.

Hands on hip and in full command of his audience, he would demand: “Do you give in?” and later say of a particularly successful show: “By heck, we took no prisoners that night.”

Dodd, who died at the age of 90 on Sunday, continued to perform right through to his later years, bringing the energy and stamina of a man half his age to his manic routines in theatres up and down the land. There was no let-up in his astonishing ability to reel off joke after joke, with the rapidity of a machine gun for literally hours on end.

Even when he was taken to hospital for a “minor operation” on New Year’s Eve in 2007, it came just hours after completing a four-hour sell-out gig at Liverpoool’s Philharmonic Hall.

But behind the hair, teeth and offbeat humour dwelt a mass of contradictions and insecurities.

Spending almost the entirety of his life based at his childhood home – a rambling mansion in Knotty Ash in Liverpool – his carefully guarded private life received an unwelcome airing in 1989 when he endured a five-week trial accused of tax fraud. He was acquitted following a brilliant defence by George Carman QC.

After 35 years in show-business, he told the court: “Since I am stripped naked in this court, I might as well tell you the lot.”

He explained: “I am not mean, but I am nervous of money, nervous of having it, nervous of not having it,” and described money as a yardstick of success – “important only because I have nothing else”.

The trial transformed Liverpool Crown Court into a sell-out theatre, with fellow comics Eric Sykes and Roy Hudd called as character witnesses.

His counsel described him as a fantasist stamped with lifelong eccentricities – such as keeping love letters in a safety deposit box and hoarding £336,000 in the attic – due to a close-knit family upbringing.

Dodd would later joke publicly about the case, but it was far from being a laughing matter at the time.

He was known by colleagues for being careful with cash and when he was earning up to £10,000 per month, he told accountants that he lived on annual expenses of just £3,500, had not bought a new suit for two or three years and never had a holiday until he was 51.

The entertainer’s career kicked off after his father bought a Punch and Judy for his eighth birthday, and he began charging school friends twopence to sit on orange boxes and watch the puppets. It was a penny to stand at the back and a cigarette card for the hard-up.

He left school at 14 and worked with his brother Bill, heaving Arley cobbles and Houlton kitchen nuts for six years as part of his father’s business.

But in his spare time, the former choirboy was singing and developing a stand-up comic routine at working men’s clubs – script by his father, costumes and general support by Mrs Dodd. He would describe himself as “Professor Yaffle Chuckabutty. Operatic Tenor and Sausage Knotter.”

The Theatre Royal, Nottingham, saw his £75-a-week debut in 1954 as Professor Chuckabutty, and within two years he was topping the bill at Blackpool, with bits such as the famous Diddy Men, the Broken Biscuit Repair Works, the Jam Butty Mines, the Moggy Ranch and the Treacle Wells.

This was followed by countless BBC series, including The Ken Dodd Show, Beyond Our Ken and Ken Dodd’s Laughter Show, and he entered the big time in 1965 with the longest-ever run at the London Palladium (42 weeks).

In 1994, his Ken Dodd: An Audience with Ken Dodd show was filmed and released on video, followed in 1996 by the Ken Dodd: Live Laughter Tour and then Another Audience With Ken Dodd in 2002.

Also a well-known singer, in 1964 he released his first single, Happiness, followed by smash hit, Tears, the following year, and then Promises.

Over the 1960s, he entered the Guinness Book of Records for the longest joke-telling session ever – 1,500 jokes in three-and-a-half hours.

Dodd married his partner of 40 years, Anne Jones, on Friday. His first fiancee, Anita Boutin, died of a brain tumour in 1977 aged 45 after 24 years together. He later found love again with Anne, a former Bluebell dancer.

He was awarded an OBE in 1982 and was dubbed a knight by the Duke of Cambridge in 2017 – the year of his 90th birthday – in recognition of both his comedic legacy and his charity work.

For the milestone birthday on November 8, he was honoured by the Knotty Ash community with a party serving up jam butties and Diddy pies at Liverpool Town Hall.

A Freeman of the City, he told the Liverpool Echo of the impressive anniversary: “There’s nothing you can do about it. It’s compulsory! And it’s no use living in the past – it’s cheaper but you can’t live in the past.

“Knotty Ash is my home – it’s the centre of my life and always has been. My family are still here with me in memories. I had the most wonderful family – fabulous mother and father, and wonderful brother and sister.”

Days previously, he shared his showmanship techniques with the Guardian, telling the newspaper: “You’re like a gladiator. You buckle on your sword and helmet and you have to take on the audience.

“You have to do a show with an audience and structure the act so that you start with the ‘hello’ gags, then the topicals, then the surreal stuff… Eventually, you can go wherever you want and say whatever comes into your head: ‘How many men does it take to change a toilet roll? I don’t know. It’s never been done’.”

“A performer has to have something in his or her psyche I would call ‘a comic imp’… That imp is always with you sitting on your shoulder or in your shadow.”

As he marked more than 60 years of performing he vowed to the Mirror newspaper, and his fans: “I can’t let the British public down, as long as they keep turning up – I’ll be there to give back the enormous happiness they’ve given me.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe