THE Crown Prosecution Service has announced that charges have been brought against six individuals relating to the Hillsborough disaster.

The announcement was made to families of the victims at a private meeting this morning.

Among those charged is the Match Commander for South Yorkshire Police on the day of the disaster, former Chief Superintendent David Duckenfield, who is accused of manslaughter by gross negligence of 95 of the victims.

Sue Hemming, Head of the CPS Special Crime and Counter Terrorism Division, said: said a further file from the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) on the conduct of West Midlands Police still needs “additional investigative work”.

She added: “Additionally, just this week, the IPCC has referred two further suspects which are unconnected to the matters sent to us in January; these subjects are subject to ongoing consideration by the CPS. We will announce our decisions in due course.

“The suspects referred to the CPS included individuals and organisations.

“Following these thorough investigations and our careful review of the evidence in accordance with the Code for Crown Prosecutors, I have decided there is sufficient evidence to charge six individuals with criminal offences.”

All the defendants, except Duckenfield, will appear at Warrington Magistrates’ Court on August 8.

Here is the Crown Prosecution Service’s statement in full regarding the Hillsborough charging decisions:

The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) has today (28 June 2017) announced its charging decisions in relation to the Hillsborough disaster and its aftermath.

Sue Hemming, the CPS Head of Special Crime and Counter Terrorism Division, made the announcement to families of the deceased at a private meeting in Warrington this morning.

She said: “Following our careful review of the evidence, in accordance with the Code for Crown Prosecutors, I have decided that there is sufficient evidence to charge six individuals with criminal offences.

“Criminal proceedings have now commenced and the defendants have a right to a fair trial. It is extremely important that there should be no reporting, commentary or sharing of information online which could in any way prejudice these proceedings.”

Charges have been authorised against:

- David Duckenfield, who was the Match Commander for South Yorkshire Police on the day of the disaster

- Graham Henry Mackrell, who was Sheffield Wednesday Football Club’s company secretary and safety officer at the time of the disaster in 1989

- Peter Metcalf, the solicitor acting for the South Yorkshire Police during the Taylor Inquiry and the first inquests

- Former Chief Superintendent Donald Denton of South Yorkshire Police

- Former Detective Chief Inspector Alan Foster of South Yorkshire Police

- Norman Bettison, a former officer with South Yorkshire Police and subsequently Chief Constable of Merseyside and West Yorkshire Police

The decisions have also this morning been relayed to other interested parties, including the defendants and other suspects who were referred to the CPS by Operation Resolve and the Independent Police Complaints Commission.

The full statement that Sue Hemming provided to those in attendance at this morning’s meeting is below:

SUMMARY OF DECISIONS

The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) has considered two substantial files of evidence from Operation Resolve (OR) and the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) in respect of 15 and six suspects respectively.

The suspects referred to the CPS included individuals and organisations. The offences referred for consideration include gross negligence manslaughter, misconduct in public office, doing acts tending and intending to pervert the course of justice, health and safety at work and safety of sports ground offences.

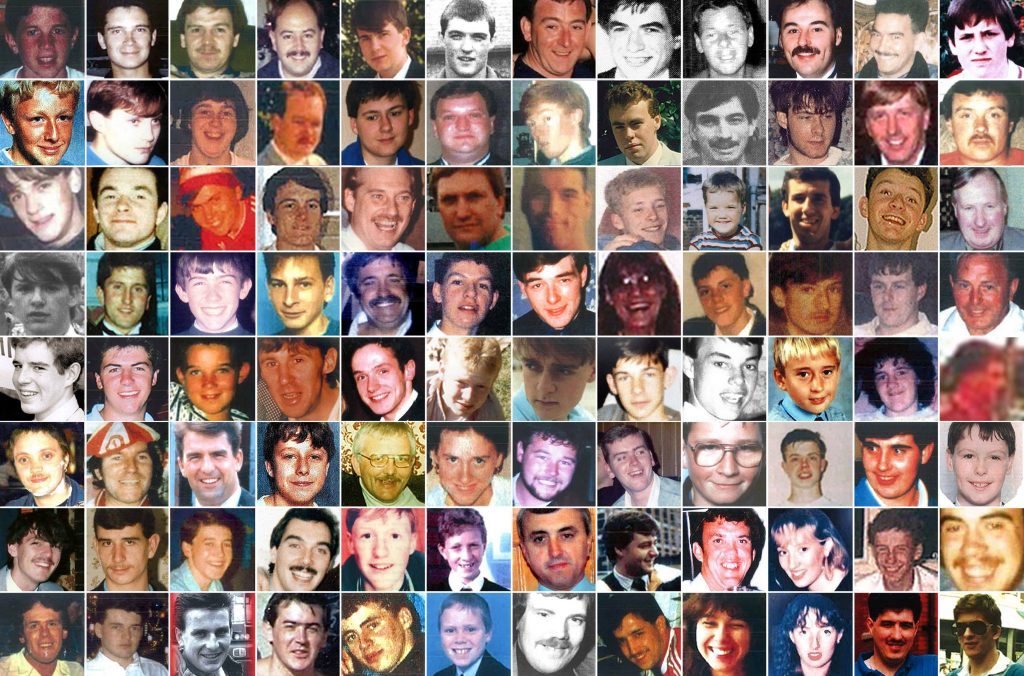

Operation Resolve investigated the events of the 15 April 1989 when 96 Liverpool fans were tragically killed as the result of overcrowding in the central pens at the Leppings Lane end of the Hillsborough football stadium.

The IPCC investigated the aftermath. In particular they looked at the conduct of South Yorkshire Police (SYP) and carried out an investigation into whether anyone was responsible for a “cover up” of the true events and if witness statements were altered in such a way to amount to a criminal offence. The CPS team and senior counsel have been advising in respect of these matters from an early stage.

Following thorough investigations and careful review of the evidence in accordance with the Code for Crown Prosecutors, I have decided that there is sufficient evidence to charge six individuals with criminal offences.

I have found that there is sufficient evidence to charge former Chief Superintendent David Duckenfield, who was the Match Commander on the day of the disaster, with the manslaughter by gross negligence of 95 men, women and children.

We will allege that David Duckenfield’s failures to discharge his personal responsibility were extraordinarily bad and contributed substantially to the deaths of each of those 96 people who so tragically and unnecessarily lost their lives.

The offence clearly sets out the basis of those allegations. We are unable to charge the manslaughter of Anthony Bland, the 96th casualty, as he died almost four years later. The law as it applied then provided that no person could be guilty of homicide where the death occurred more than a year and a day later than the date when the injuries were caused.

In order to prosecute this matter, the CPS will need to successfully apply to remove the stay imposed by a senior judge (now retired) at the end of the 1999 private prosecution when David Duckenfield was prosecuted for two counts of manslaughter by gross negligence. We will be applying to a High Court Judge to lift the stay and order that the case can proceed on a voluntary bill of indictment.

Graham Henry Mackrell, who was Sheffield Wednesday Football Club’s company secretary and safety officer at the time, is charged with two offences of contravening a term of condition of a safety certificate contrary to the Safety of Sports Grounds Act 1975 and one offence of failing to take reasonable care for the health and safety of other persons who may have been affected by his acts or omissions at work under the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974. These offences relate to alleged failures to carry out his duties as required.

Peter Metcalf, who was the solicitor acting for the South Yorkshire Police during the Taylor Inquiry and the first inquests, is charged with doing acts with intent to pervert the course of public justice relating to material changes made to witness statements.

Mr Metcalf, an experienced solicitor, was instructed by Municipal Mutual Insurance to represent the interests of the force at the Taylor Inquiry and in any civil litigation that might result from the Hillsborough Disaster.

He reviewed the accounts provided by the officers and made suggestions for alterations, deletions and amendments which we allege were directly relevant to the Salmon letter issued by the Taylor Inquiry and for which there appears to be no justification.

Former Chief Superintendent Donald Denton and former Detective Chief Inspector Alan Foster are similarly charged for their involvement in the same matter. It is alleged that Donald Denton oversaw the process of amending the statements and in doing so, he did acts that had a tendency to pervert the course of public justice and we will say that Alan Foster was central to the process of changing the statements and took action to do so.

Former Chief Constable Norman Bettison is charged with four offences of misconduct in public office relating to telling alleged lies about his involvement in the aftermath of Hillsborough and the culpability of fans. Given his role as a senior police officer, we will ask the jury to find that this was misconduct of such a degree as to amount to an abuse of the public’s trust in the office holder.

The defendants, other than David Duckenfield, will appear at Warrington Magistrates’ Court on 9 August 2017.

May I remind all concerned that criminal proceedings have now commenced and of the defendants’ right to a fair trial. It is extremely important that there should be no reporting, commentary or sharing of information online which could in any way prejudice these proceedings.

In relation to six other police officers who were referred as suspects in respect of their conduct in planning for the match or on the day, there is insufficient evidence for a realistic prospect of conviction.

I have concluded that whilst there is evidence of failure to meet the standards of leadership rightly expected of their respective ranks, there were no acts or omissions capable of amounting to gross negligence manslaughter or “an abuse of the public’s trust” to the required criminal standard for an offence of misconduct in public office.

I also considered administration of justice offences against some of these officers. However, the evidence did not establish either a tendency to pervert the course of public justice, nor an intention to pervert the course of public justice to the required criminal standard. Neither did the material considered establish sufficient evidence, as required for the purposes of perjury, that statements were made on oath which the author knew to be false or did not believe to be true.

I have decided not to prosecute the company which was the legal entity of Sheffield Wednesday Football Club at the time as it only now exists on paper.

There are no directors or others listed who form the company and therefore no-one who can give instructions to answer any criminal charge or enter a plea. Even if the company was to be prosecuted and found guilty in these circumstances, there could be no penalty as it does not have any assets with which to pay a fine.

For legal reasons, we cannot prosecute the South Yorkshire Metropolitan Ambulance Service and there is insufficient evidence of a criminal offence against the two most senior employees referred for consideration.

There is, however, sufficient evidence of a health and safety breach against one junior ambulance employee, although it is “non causative” which means that it cannot be directly connected to any particular death.

As we cannot prosecute the ambulance service or the more senior employees and the offence carries a maximum penalty of a fine, I have decided that it is not in the public interest to prosecute the junior officer after this significant period of time when the likely outcome would be a nominal penalty.

Finally, in relation to Operation Resolve, the Football Association (FA) was also considered in relation to the day’s events. Its conduct was assessed against the Safety of Sports Grounds Act and the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974.

While I considered that it was a “responsible person” for the purposes of Safety of Sports Grounds Act, there was insufficient evidence to establish that any breach of the safety certificate could be placed within the responsibility of that organisation, and thereby raise a burden on it as a defendant to establish a due diligence.

Equally, for the purposes of Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974, the evidence did not establish that, in the conduct of its undertaking, the FA contributed to a material risk to safety. As a result, in each instance, there was not a realistic prospect of a conviction against them. In the particular circumstances, it also followed that there was insufficient evidence against any employee of that organisation under either Act.

In respect of the other suspects referred for consideration of criminal offences arising from the IPCC investigation into the statement changing, there is insufficient evidence to prove an intention to pervert the course of public justice.

Note – It is not the function of the CPS to decide whether a person is guilty of a criminal offence, but to make fair, independent and objective assessments about whether it is appropriate to present charges for the criminal court to consider.

My assessment of the case is not in any sense a finding of, or implication of, any guilt or criminal conduct. It is not a finding of fact, which can only be made by a court, but rather an assessment of what it might be possible to prove to a court, in accordance with the Code for Crown Prosecutors.

There is a further IPCC file into the conduct of the West Midlands Police but additional investigative work was required in respect of this. Additionally, just this week, the IPCC has referred two further suspects which are unconnected to the matters sent to us in January. These files are subject to ongoing consideration by the CPS and we will announce our decisions in due course.

SUSPECTS AGAINST WHOM THE FULL CODE TEST IS NOT MET

Operation Resolve suspects:

I carefully considered the actions of six other police officers of various ranks in respect of their conduct in planning for the match and/or on the day.

There was a failure to define roles and task responsibility to those acting in command and this has made it extremely difficult to demonstrate matters which fell within the specific performance or discharge of duties owed by individual officers and there was a lack of specific instructions as to how any duty should be carried out.

I have concluded that whilst there is evidence of failure to meet the standards of leadership rightly expected of their respective ranks, there were no acts or omissions capable of amounting to gross negligence manslaughter or ‘an abuse of the public’s trust’ to the required criminal standard for an offence of misconduct in public office. Prior to 1998, no police force or individual police officer was subject to the provisions of the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 (HSWA).

As indicated, we also considered administration of justice offences against some of these officers.

However, the evidence did not establish either a tendency to pervert the course of public justice, nor an intention to pervert the course of public justice to the required criminal standard. Neither did the material considered establish sufficient evidence, as required for the purposes of perjury, that statements were made on oath which the author knew to be false or did not believe to be true.

Sheffield Wednesday PLC (company number 00062478) is the legal entity, existing only on paper, which was Sheffield Wednesday Football Club in 1989.

Sheffield Wednesday Football Club as it exists today is a different company and as it is not a successor organisation, is not criminally liable for any offences that might have been committed.

Operation Resolve took action to preserve the paper company at the outset of the investigation so that a full investigation could take place. There are no longer any directors or other individuals who form the company and therefore no-one who could represent it in the dock, give instructions to answer any criminal charge or enter a plea.

Even if the company were to be found guilty in those circumstances, there could be no penalty as it does not have any assets with which to pay a fine and no-one else liable to pay it. As a consequence, whilst I have concluded that there is sufficient evidence for a health and safety offence, it is not in the public interest to prosecute now.

We considered the actions of the South Yorkshire Metropolitan Ambulance Service, which has been criticised for its failure to respond adequately to the unfolding disaster.

It is clear that SYMAS was a service supplied by the Trent Regional Health Authority (TRHA) rather than a legal entity itself. The TRHA ceased to exist when its responsibilities were transferred. However, criminal liability was not transferred to the successor organisations, so there is no body, corporate or incorporate, which can now be prosecuted even if liability could be proven.

We have considered the actions of three ambulance service employees. We examined the records of the TRHA and neither of the more senior officers (or by definition the junior officer) is capable of amounting to a ‘senior manager’ under section 37 of the HSWA.

We therefore considered whether any of the three might have committed any other HSWA offence and in doing so considered expert evidence in respect of the SYMAS response. The expert is critical of the overall response but is unable to quantify the effect that any failings had on the victims. Any identifiable breach therefore, would be ‘non-causative’.

The expert summarises his view as follows:

“The actions of the SYMAS staff that were present at the match from the outset, and those that attended as a result of being sent to the disaster must be considered in the light that this was an event that had developed very quickly, resulting in very high numbers of dead and dying patients in a very short space of time.

“This was an event that occurred right in front of the SYMAS staff and the police, and they did not have the luxury of even a minute’s thinking time.

“This disaster would have proved extremely challenging for even the most experienced Ambulance Officers, Ambulance Staff and Ambulance Control Staff to have dealt with in a structured manner.”

He says that whilst there were failures and consequences flowing from the actions of the ambulance staff “it may be that these failures that in my opinion arose from inexperience both of planning for, and dealing, with Major Incidents rather than from deliberate omission or commission of acts”.

One of the senior officers assumed no role in dealing directly with the casualties at the stadium. He was at home then consequently went to the SYMAS control room at 1550 after becoming aware of the disaster; this was after the initial casualty transport phase had come to an end.

He was later concerned in the arrangements to deal with the deceased and to stand down the ambulance service resources but there is insufficient evidence that in his actions or conduct, he failed to show reasonable care under the HSWA so as to amount to an offence.

The second senior employee failed to declare a major incident at a stage when he had sufficient information to do so. However the extent of his individual failure should be considered against the context:

- the police had not declared a major incident to SYMAS,

- the SYMAS liaison officers at the ground had not declared a major incident, and

iii. the receiver of the message at control was not prompted to declare one.

It seems that this employee felt that he had insufficient information and so made the decision to attend the ground himself. His decision to go to the ground was described by the expert as the correct one, and as a decisive action.

Once at the ground, he became the most senior ambulance officer and should have assumed the role of “Incident Officer” according to the SYMAS Major Incident Plan.

The evidence and RACAL tapes make clear that ambulances and SYP were still seeking a SYMAS officer some time after his arrival. However, the expert’s evidence was that his actions were commensurate with a senior officer trying to establish control and command.

Other witnesses commented on him later attending the gym and taking control of the situation.

In all of the circumstances, and particularly having reflected on the nature of the duty owed under s.7 HSWA and the relevant considerations, I decided that there is insufficient evidence capable of establishing that this suspect failed to show reasonable care for the health and safety of other persons affected by his acts or omissions at work on the 15 April 1989.

Consequently, there can be no prosecution for health and safety breaches arising from the conduct of the two most senior officers on the day.

The most junior officer was the second station officer (the first, more senior, station officer has since died).

This junior officer’s failings on the day contributed to a delayed response from SYMAS, including a delay in the notification of the hospitals and request of a mobile medical team, the dispatch of the major incident vehicle, and a delay in asserting command and control of the incident.

There were other (unconnected) opportunities for a major incident to be declared; namely by the police, and by Control in receipt of the messages requesting ambulances. The failings were certainly not this suspect’s alone.

However, he was in the position of being the “eyes and ears” of SYMAS in the ground and the first and best positioned SYMAS employee to be able to make a proper assessment. The first few minutes were critical and a better response might have made a difference to survival.

I was satisfied, therefore, that there is sufficient evidence that this suspect failed to take reasonable care for the safety of those who may be affected by his acts and omissions at work as a Station Officer, namely the supporters in the pens, by his failure to look in the pens and failure to declare a major incident.

At the same time, though, in applying the public interest stage of the Code Test, I took account of the following:

- This suspect did not create the circumstances of the crisis he faced; and his reaction to it, while entirely inadequate, cannot be proven to have directly caused any deaths;

- The offence was neither flagrant on his part, nor did it involve the showing of a reckless disregard for health and safety. Rather, it may very well have arisen from a reaction of shock on the part of this emergency responder confronted by an unfolding tragedy of enormous scale out with his experience. In the words of the expert, this suspect was ‘not well enough prepared by his employer’ in relation to this match;

- Moreover, there were a significant number of failings on the part of other individuals (police officers and other SYMAS staff) which also contributed to delaying treatment and effective organisation of treatment of casualties.

Therefore, given that (i) we are unable to prosecute SYMAS or the more senior officers for the overall poor response; (ii) the application of Health and Safety Executive policy would be unlikely to result in a prosecution of an individual in these circumstances; (iii) the offence was non-causative; (iv) a considerable amount of time has passed; (v) the offence only carries a fine; and that (vi) a nominal penalty would be the likely outcome, I have found that the factors against prosecuting this suspect outweigh those in favour. In those circumstances, it is not in the public interest to prosecute that individual alone.

Finally, we considered the conduct of the Football Association and one of its officers. That organisation’s conduct was assessed against the Safety of Sports Grounds Act and the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974. While I considered that it was a ‘responsible person’ for the purposes of SSGA, there was insufficient evidence to establish that any breach of the safety certificate could be placed within the responsibility of that organisation, and thereby raise a burden on it as a defendant to establish a due diligence.

Equally, for the purposes of HSWA, the evidence did not establish that, in the conduct of its undertaking, the FA contributed to a material risk to safety. As a result, in each instance, there was not a realistic prospect of a conviction against them. In the particular circumstances, it also followed that there was insufficient evidence against any employee of that organisation under either Act.

IPCC suspects:

We considered the actions of two other suspects referred for consideration in connection with the statement changing.

In respect of these former officers who were on the team that was tasked with making amendments, it is not possible to show to the criminal standard that they were aware of the overall system being implemented and in the absence of evidence to show that they were aware of the nature, extent and impact of the relevant amendment process, it cannot be proved that they had an intention to pervert the course of public justice. If the evidence is insufficient to found an inference of criminal intent, it follows that their conduct cannot give rise to charges of misconduct in public office.

Sue Hemming, Head of Special Crime and Counter Terrorism Division, 28 June 2017

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe