It took a bit of doing, but Graeme Souness managed to attract more controversy after last Sunday’s Chelsea-Spurs clash than the London derby itself.

In his analysis of referee, Anthony Taylor’s performance, the Liverpool, Rangers and Scotland icon said: “It’s a man’s game all of a sudden again.”

That proved as inflammatory as any of the “meaty” challenges from his own playing career.

With England’s Lionesses having won the Euros in front of a record crowd just a few weeks earlier, Souness’s comments were branded “disgraceful”.

The critics did not miss their target and, the following day, Souness issued a clarification.

He said he’d been referring to the Premier League games he’d watched last Sunday, rather than the sport of football that was a game for everyone to enjoy.

His argument was that English referees are letting more go this season, allowing games to flow and making them a better watch for viewers.

That hasn’t come around by accident. The officials were briefed before the season kicked-off that they should not to be blowing their whistles every time a player goes to ground.

The move is a nailed-on vote winner. Over-officious refereeing, and players diving for fouls, are common bugbears with fans.

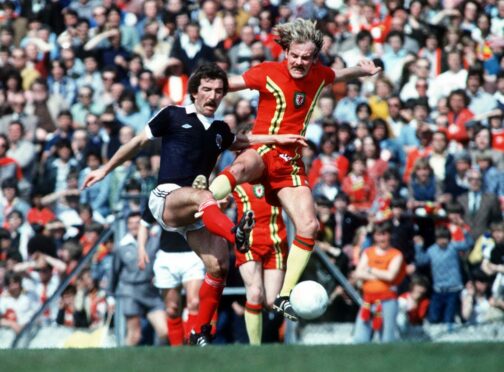

There are plenty who hanker back to the old days when crunching tackles were allowed and bust-ups were commonplace and, indeed, part of the entertainment.

Look no further than the ferocious 1970 FA Cup Final replay between Leeds United and Chelsea at Old Trafford.

Assessing the game a couple of years ago, Premier League ref Michael Oliver said he would have shown ELEVEN red cards. Eric Jennings, the man who was in charge of what is considered one of the most-brutal games in English football history, made just one booking.

It was a laissez-faire approach, summed memorably by the late Scottish journalist, Hugh McIlvanney, who wrote: “At times, it appeared that Mr Jennings would give a free-kick only on production of a death certificate.”

Fifty-two years on, the game may have changed, but there still has to be a balance between allowing the game to flow and players’ welfare.

One that ensures flair players are protected because, for the most part, they are the ones who everyone wants to watch.

And at the same time, one which is not so skewed in favour of attackers that defenders are not able to play their natural games.

Referees insist they have always tried to achieve that. The difference is in the interpretation of the rules at any given time.

Probably the easiest way to track the difference is through the foul count.

The clash between Chelsea and Spurs was very feisty, yet only contained 18 fouls. Or, rather, there were only 18 fouls awarded and three yellow cards shown.

Anthony Taylor also sent off both managers, Antonio Conte and Thomas Tuchel, but that was for a separate incident after the full-time whistle had blown.

For comparison, in Rangers’ Premiership opening day win at Livingston, Don Robertson booked seven players and blew up for 32 fouls.

I was there, and also in my armchair last Sunday. The referees’ approach to the encounters was strikingly different.

Of course, Scottish officials were not given the “go-easy” directive.

Different league, different governing bodies.

We may well end up moving in the same direction. Trends are as prevalent in football as they are in any other walk of life.

The English Premier League wields a powerful influence on the game throughout the world, and it certainly helps shape practice north of border.

SPFL chief, Neil Doncaster, admitted as much when he talked of Scotland’s late take-up of VAR allowing us to learn lessons from England’s use of the system.

If so, logic suggests the key would be in the degree to which refs let things go in search of a game that is ever better to watch.

A pursuit that suggests Graeme Souness was only a letter out. Modern football – it’s a fan’s game.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe