WITH a death toll of up to 100 million, Spanish flu was the greatest human disaster of the 20th Century.

Laura Spinney, author of new book Pale Rider (Jonathan Cape £20), tells Bill Gibb The Honest Truth about the catastrophic pandemic.

When did Spanish flu hit and what was it?

The first cases were officially recorded in March, 1918, and the last around March, 1920.

It was caused by the flu virus, an exceptionally virulent strain.

Who was the first case?

It was Albert Gitchell, a cook at Camp Funston, a US Army base in Kansas.

He fell sick with a sore throat, fever and headache, went to the infirmary and hundreds of people followed him.

That was the first documented case although there may have been others before as there was no diagnostic test at that time.

How did the pandemic develop?

In three waves. The first wave which caught Albert (who survived) was in spring, 1918, and was more like a seasonal flu from which most people recovered.

It receded and came back a few months later and that autumn wave was really deadly.

Many people mistook it for a variant on bubonic plague which is spread by the breath, like flu.

There was a third wave in early 1919.

What were the symptoms?

It started with average flu symptoms – cough, headache, fever – then just got worse.

Patients had trouble breathing and would haemorrhage from the nose and mouth. Then their faces would characteristically turn blue.

Fingertips and extremities would go from blue to black and the black would spread over the entire body.

Once you started to turn black that was basically it, your chances of recovery were close to zero.

What was the death rate like?

Again, most people recovered, but many more died than in a normal flu season.

The fatality rate was 2-5%, whereas it’d usually be more like 0.1%.

So it was 25 times more lethal.

What was the treatment?

There really wasn’t any.

There was no effective vaccine and anti-virals wouldn’t be invented for decades.

The thing that killed most patients was pneumonia, a secondary bacterial infection of lungs that had already been weakened by the flu virus.

Doctors were essentially helpless. They tried all sorts of things which weren’t effective as they were sure flu was caused by a bacterium.

Did anything work?

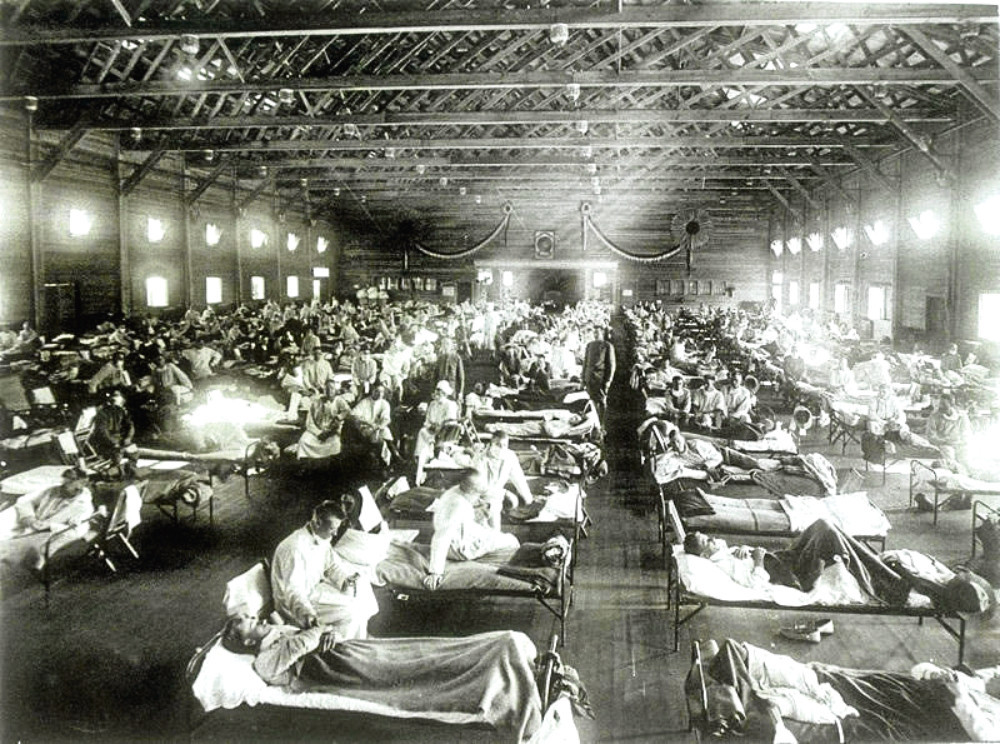

The only thing that really made a difference was good nursing.

Keeping the patient warm, hydrated and feeding them every now and then.

That was what gave patients the best chance of pulling through.

Did it hit everybody the same?

No. Normally with flu, the very young and old are targeted but here it really also hit those between 20 and 40 and mainly men.

So you often had the tragic situation where a guy would survive the First World War, but die of Spanish flu.

It tore the heart out of families and communities.

And did it hit everywhere equally?

There was a massive geographic variation.

Asians were about 30 times more likely to die of the flu than Europeans on average.

Isolated places such as Alaska or the Australian Outback were badly affected, partly because they hadn’t been much exposed to flu historically, so their immune systems weren’t primed to deal with it.

The place that lost the highest percentage – up to 22% – was Western Samoa. India lost about 18 million people, the largest number in any single country.

To put that in context, the entire death toll of the First World War is normally estimated at 17 million.

Could something like Spanish flu happen again?

Yes, certainly.

If a strain developed as novel as the one that erupted 100 years ago, we could have big problems.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe