Her childhood fantasy of becoming a film-maker led Jessica Fox to the bright lights of Los Angeles, but it was under the dark skies of Dumfries and Galloway where her dream became a reality.

Fox’s first feature film, Stella, which she wrote and directed during the pandemic in her adopted home of Wigtown, last week won acclaim at a prestigious international film festival.

For Fox, the story could not have been set anywhere else as her script melded her grandparents’ survival of the Holocaust and migration to America; the popularity of fascist Oswald Mosley in parts of south-west Scotland in the 1930s; her love of the original folk-tale version of Cinderella; and the location of 18th Century, A-listed Galloway House, where she was permitted to film much of the movie.

The plot follows Stella, a 20-year-old Jewish student played by Edinburgh actress Oli Fyne, who is living in Oxford but ends up penniless after losing touch with her parents in Germany.

She finds work as a German tutor at the House of Rig in south-west Scotland but when she discovers the family supports Mosley and his fascist regime, which has made inroads in the area, she has to hide her true identity. But her cover story unravels when she falls in love with Will, who she finds trespassing on the estate, when it transpires that he is actually the son of the Earl of Rig.

Fox, originally from Boston, said: “I began writing it during lockdown. I knew about Galloway House, which is so beautiful, and when the owner, Kamal, was generous enough to allow me to film there it allowed me to write the story based on the location. We also filmed in Wigtown.

“I studied folklore, mythology and astronomy at college and I’ve always loved old fairytales. I like the folk version of Cinderella, where she has to leave her home and identity and start again, with a magic chest full of her possessions that sinks into the ground and follows her wherever she goes. It was the story of a refugee and this was a heroic version of Cinderella that I wanted to tell.

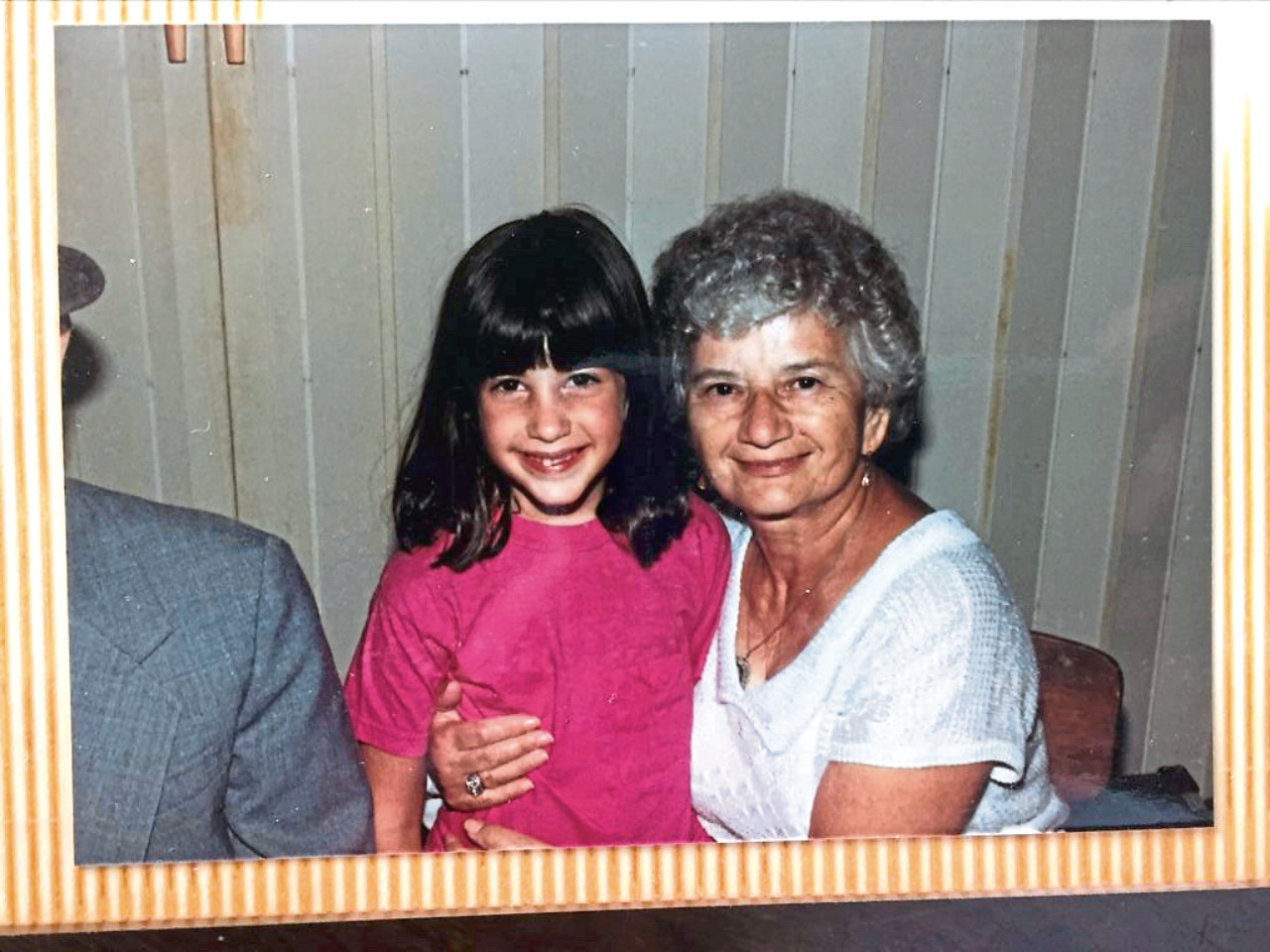

“My family story is one of refugees, as my mum came to America when she was young after the war. My grandparents were holocaust survivors and had to start over. My gran talked about that time and was always passionate about refugees but my grandfather never spoke much about it. I know he was in Auschwitz and helped to run an underground hospital. He was a watchmaker so was able to fix things for the Nazis in exchange for medicines.

“I really liked the idea of setting the film in 1937 because it was an interesting time period in Scotland, during an economic depression where handfuls of families were Nazi sympathisers.

“As I researched and learned about Mosley coming to Dumfries and holding a rally there, it wasn’t too much of a stretch to imagine he might have come to visit one of his patrons, so he turns up in my story to visit the House of Rig.

“We had a lot of young people on the film set and when I asked them what they thought of Mosley, they said they thought I had made him up, which shows that it’s important to tell stories from history so that we don’t forget. The film is a story that I think resonates with people and draws parallels to today.”

It should be no surprise to see Fox come up with such an inventive plotline, considering it was her active imagination that led to her moving to Scotland’s official book town 15 years ago. She had already moved across the States to LA to take up a position as a storyteller with Nasa, going around campuses with scientists while during the evenings she would produce short films and commercials and was the videographer for the band, The Dresden Dolls.

She said: “At night, I’d be sitting trying to write my stories and I would constantly see this image of a young girl behind the counter of a bookshop, where it was raining outside. I just knew it was Scotland, even though I had never visited.

“The more I had the vision or daydream, I realised the girl was me, so I typed ‘used bookshop Scotland’ into Google and Wigtown came up.

“I contacted the first bookshop on the list, came here for a holiday, fell in love with the bookshop owner, got married, divorced, both of us wrote books, and fast forward to now and I’m still here because it’s my home.”

The month-long shoot for Stella utilised an all-female production team, a mix of established and up-and-coming talent in front of and behind the camera, and a host of local volunteers who all worked within a Covid bubble to make sure the film was made.

The movie was completed on a tiny budget, financed by private investors.

“While it’s tough, one of the joys of indie film-making is you have more control over the time you can do it in,” said Fox.

“After writing the script I wanted to fundraise, prep, do pre-production, cast, film, edit, complete post-production and apply to my first film festival all within a year, and we did it.

“We had a much smaller budget than usual for a costume drama – too small to be awarded a lot of the grants that exist in Scotland. On one hand, it was frustrating but on the other hand it meant we didn’t need to wait for grants and went to private funders who were invested in the story and area. Our priority was to hire locally and there’s an embarrassment of riches in the area but people who live in rural communities don’t often get the same chance.”

Fox’s contacts book meant she was able to call on the expertise of film-makers like Jason Lust, who worked with The Jim Henson Company and produced the hit Peter Rabbit movie, and Richard Tulk-Hart, whose productions include Dougray Scott’s Crime for Britbox. Leading the cast is Billy Elliot and Outlander star Gary Lewis.

“Gary actually spent time at Galloway House when he was a school pupil,” Fox said. “One of its former uses was as a place where inner city kids could come for the summer and enjoy the countryside, and Gary was chosen to come from Glasgow one year.

“He was going round the rooms explaining to us what each one had been used for and he still had an old notebook of drawings he did while he was there.

“Gary’s daughter also has a part in the film, and for Oli Fyne and Louis Hall, who play Stella and Will, this was their first feature film.”

Stella received its world premiere at the Tel Aviv International Film Festival where it won best drama and last week it received the best first-time film-maker award at the Montreal Independent Film Festival. Fox says the recognition will help the movie find a wider audience and also assist in her future projects.

“For an indie film, to get recognition and visibility and meet other contacts is so important,” she added. “When we were in Tel Aviv, people were coming up asking if the locations were real.

“I can’t imagine anywhere else where people would be as supportive as they have been here. I love the collaborations we had on Stella, and now we’ll see where else we go with the festivals and then we’ll look at the best option for distribution, because the more people who see it the better, and then it will be on to another feature with the same team.

“It thrills me that Cinderella was Jewish, and I loved looking at the time period and the themes of identity, home and sense of belonging. To explore them in a place that has been so welcoming to me as an immigrant was very important and exciting for me, too.”

When Dumfries turned out for fascist leader of the Black Shirts

As his Blackshirt supporters violently ejected Communist protesters, Sir Oswald Mosley addressed a packed crowd of more than 3,000 locals in the Drill Hall in Dumfries.

It was April, 1934, and the leader of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) was holding court in south-west Scotland. The meeting had been arranged by James Little, town clerk of nearby Dalbeattie, a community that had been described as “the cradle of Scottish fascism” thanks to having more than 400 members, easily outnumbering the combined membership of the BUF in Glasgow and Edinburgh.

Oswald, a former Conservative and Labour MP who was once touted as the next prime minister, spoke rousingly for two and a half hours, focusing on agriculture and a promise to put thousands back to work on the land.

It is thought one of the reasons why Oswald and the BUF found success in the area was the fact that the local economy was heavily reliant on farming and Oswald’s words about an agricultural renaissance struck a chord. Little, as a town clerk supporting the movement, helped foster respectability for the party in the area.

Local MPs Dr Joseph Hunter and Cecil Dudgeon, both Liberals, listened on from the front row as Oswald detailed his plans for agriculture, which he said would also maintain the stability of the state.

The local newspaper reported on the meeting, stating: “Sir Oswald held the complete attention of the large audience throughout and his mastery of speech and invective was very impressive”. He was described as “a brilliant orator”.

The following year, William Joyce – better known as Lord Haw-Haw – addressed a meeting of the BUF in nearby Kirkcudbright.

Oswald was inspired to set up the party after meeting Mussolini during a trip to Italy, and modelled the Blackshirts on the Italian leader’s fascist regime. But as Oswald’s party became more radical, the full invective of his stance was revealed and, when the country went to war with Germany, the BUF was prohibited.

He was detained in May 1940, just two weeks after Winston Churchill became prime minister, and was interned, spending the next three years living with his family in the grounds of Holloway Prison. He was released in late 1943 and spent the rest of the war under house arrest.

He moved to France but attempted a comeback in British politics in 1959, leading his campaign on an anti-immigration policy but took just 8.1% of the vote. He returned to France and in 1977 was nominated as a candidate to become rector of Glasgow University but he lost out to John Bell.

Oswald died in Orsay, France, on December 3, 1980.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM

© SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © AP/Shutterstock

© AP/Shutterstock