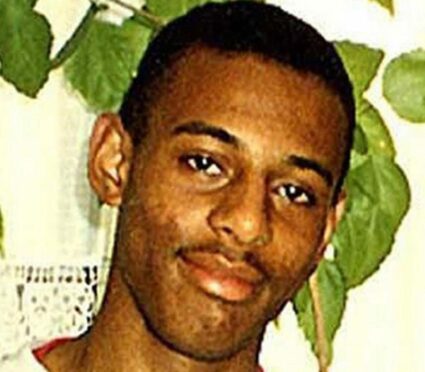

The name of Stephen Lawrence is one of the most familiar in modern British history.

No one can be unaware of how the black teenager was murdered by a gang of racists in 1993, and how his courageous and indomitable parents, Doreen and Neville, fought for justice as police investigations slowed and stalled, again and again.

But Clive Driscoll? His name is not so familiar. He is the old-school London detective who finally brought two of Stephen’s killers to justice and I was delighted to learn ITV were dramatising his investigation.

The final episode of Stephen airs tomorrow with Steve Coogan playing the gravel-voiced, hard-bitten Driscoll.

Much of my career has been spent investigating racism in the police and much of that work has, one way or another, revolved around the death of Stephen Lawrence and the repeated and abject failures of Metropolitan Police to properly investigate the murder and deliver justice to Stephen’s family.

Those failures led to the inquiry by Sir William MacPherson in 1998 when, in a watershed moment for UK race relations, the recently-retired high court judge, a meticulous Scot, concluded the action and inaction of the Met was due to institutional racism. That damning epithet has coloured the perception of UK policing ever since.

MacPherson’s report was the inspiration for the BBC’s Secret Policeman investigation, when I spent eight months undercover as a recruit to expose racism in Greater Manchester Police, when I encountered virulent, general racism in the ranks along with a nasty and specific antipathy towards the Lawrence family prompted, apparently, by how their fight for justice was impacting on the image of policing.

One of my colleagues, PC Rob Pulling, was filmed cutting holes in a pillow slip and aping a Ku Klux Klansman after making a series of obscenely offensive remarks about the Lawrences. He was, along with another nine officers, drummed out of the force after the broadcast of our film in 2003.

Two years later, I started investigating the murder of Stephen. The case was then officially dormant, after a number of reviews and reinvestigations had failed to yield enough new evidence.

Our investigation, The Boys Who Killed Stephen Lawrence, revealed a number of new leads, drove a bus through the alibis of the prime suspects and seemed to focus the minds of the Met.

Fortuitously, our film came just as Driscoll started to take an interest, so when he asked to meet, I was delighted. Our film pointed the finger firmly at the chief suspects, but that’s as far as we could go. This needed a complete reinvestigation and Clive said he was the man to do it. I believed him.

When we met he wanted to talk about how we had dramatised Stephen’s attack. For our film, we tried to recreate what happened as accurately as possible.

We had seen statements that revealed the attack on Stephen had been sustained and brutal, lasting up to 25 seconds, and that’s how we portrayed it in the film.

Driscoll was obsessed by this, and wanted to know more about why we had done it. He was convinced such a sustained attack must have left a forensic trace and that was what would provide the breakthrough.

He ordered a complete forensic review, by a new team of independent scientists and they discovered a drop of Stephen’s blood on a jacket belonging to Gary Dobson, and other fibres linked to David Norris.

It was enough to take two of the five chief suspects to trial. I remember sitting in the Old Bailey watching it unfold, and ITV’s Stephen has captured the drama of it but also the justice in it, the feeling that finally there had been, however late, however partial, an accounting for the wrong that had been done, the terrible crime that had been committed.

Coogan captures Driscoll, this understated but driven detective as he chases down every lead, while managing to keep the grieving Lawrences on side.

They, naturally, feared being let down by the Met once again, and were at first unsure whether to trust anyone with a badge. He won them over, and delivered on his promise not to rest until justice was done.

Dobson and Norris were found guilty and sentenced to life in 2012 when Driscoll was commended by the judge, who urged him to continue his investigations into the other suspects.

That would not happen and, having served 32 years, he was told his service was no longer required.He believes he was effectively forced into retirement.

The investigation was given to another detective but no more progress was made and the case is again dormant. At least three of Stephen’s killers are yet to be convicted. This troubles Driscoll, and, I suspect, always will.

A humble man, he is a little mortified at this latest brush with fame but those of us with some knowledge of the case, and that is, in truth, all of us, should be glad he is being given this attention and acclaim.

The work of DCI Driscoll is worth remembering in this atrocious case that should never be forgotten.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM