THE King of Cool.

As nicknames go, that one’s damn hard to beat.

But there’s always been the sense Steve McQueen would have given up the acting career that made him the coolest man on the planet if he could have been just as good racing cars and bikes as he was in front of the camera.

Perhaps that came from hardly knowing his father, a stunt pilot for a barnstorming flying circus, who left his mother before Steve was born, in Indiana in 1930.

What’s certain is that, after his mother sent him to live with her parents on a farm in Missouri, his uncle gave him a red tricycle on his fourth birthday and Steve himself cited that as sparking his interest in racing.

But the racetracks would have to wait.

Bounced between the farm and various abusive stepfathers, Steve became rebellious and got into scrapes with the police over petty theft and gang activities.

A stint in remand school seemed to have straightened him out, but he jumped ship to work in a brothel on his first voyage in the merchant marine.

Even when Steve joined the Marines, he couldn’t stick by the rules, busted back down to private no fewer than seven times, before he resolved to focus on self-improvement and embraced the Corps’ discipline, being honourably discharged in 1950, at just 20.

With financial assistance from the GI Bill, which helped pay former servicemen’s tuition, he studied acting in New York and soon started landing stage roles.

He made extra money by competing in weekend races at Long Island City Raceway, quickly becoming good enough to take home $100 a weekend, some of which he spent on his first bike, a Harley-Davidson.

A move to LA saw Steve break into TV and he soon had his first lead role in B-movie schlock-fest The Blob.

His breakthrough role was as the laconic bounty hunter Josh Randall in long-running TV Western Wanted: Dead Or Alive.

It was in this role that Steve perfected the anti-hero schtick that became his trademark, and he cemented his star status by stealing every scene as the taciturn second lead in The Magnificent Seven, much to Yul Brynner’s disgust.

Even then, he was toying with the idea of becoming a racing driver, with a one-off outing in the British Touring Car Championship in 1961 — driving a Mini and finishing third at Brands Hatch.

Then came what, for many, is Steve’s defining role, the one that landed him the King of Cool moniker, and one that allowed him to indulge in his love of motorcycles.

As Captain Virgil Hilts, AKA “the Cooler King” for the amount of time he spent under lock and key in the cooler, Steve created one of cinema’s most iconic characters in The Great Escape, in 1963.

And his new-found clout meant he could ask for a motorcycle sequence to be tagged onto the tale of a mass escape of POWs.

Steve did most of the stunt riding himself apart from the final, futile, leap for freedom, which insurance niceties meant had to be performed by stunt driver Bud Ekins.

Ekins also stood in for the star in his other signature role, that of the detective in 1968’s Bullitt, as although Steve spent a lot of time practising high-speed driving on San Francisco’s streets, he’s only behind the Mustang’s wheel for about 10% of the picture’s classic car chase.

Bullitt went so far over budget, Warner Bros cancelled the remaining seven films on Steve’s contract, failing to woo him back when it became a runaway success.

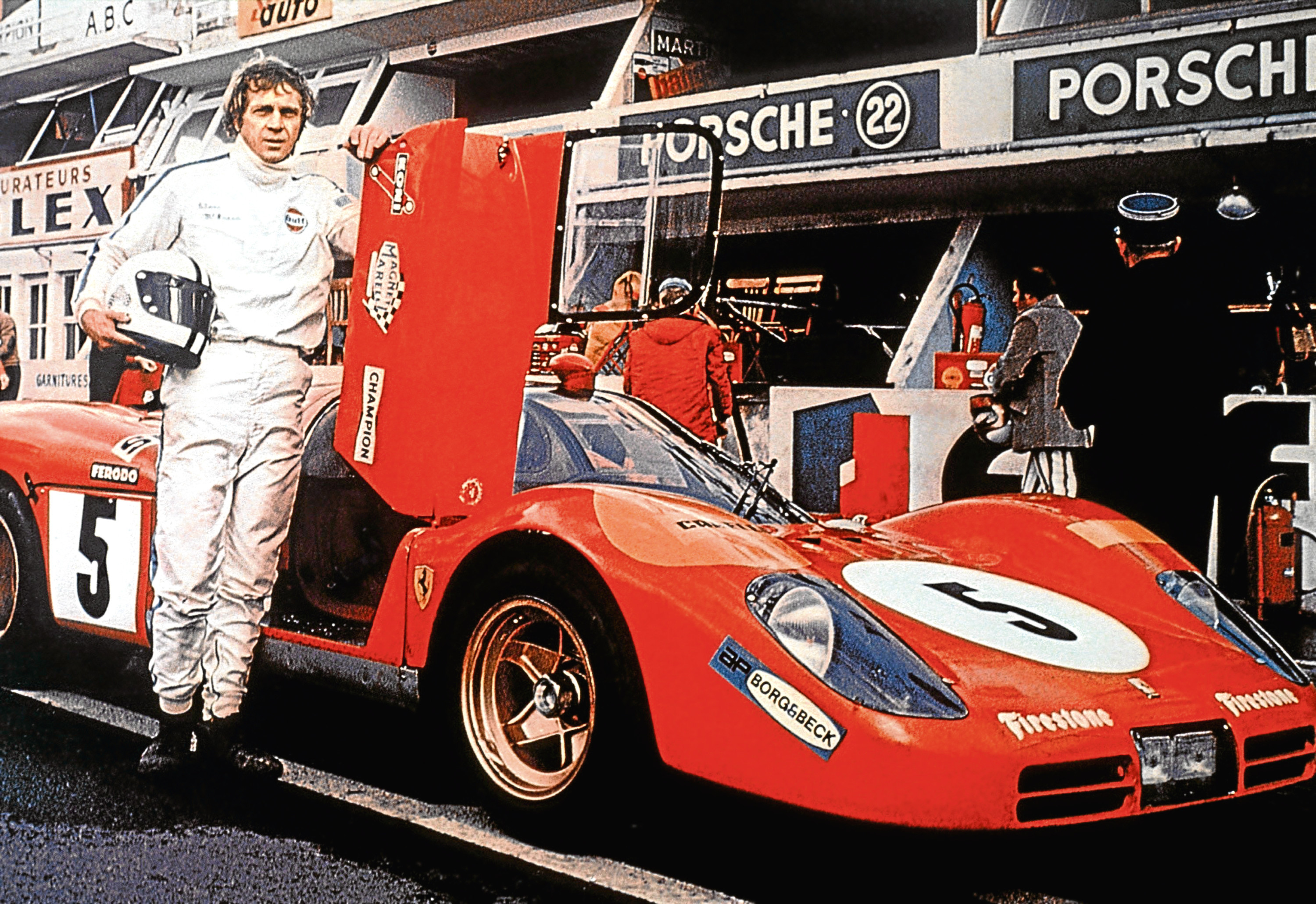

He again combined acting with his love of speed in 1971’s Le Mans, for which he’d wanted to drive a Porsche in the previous year’s 24-hour race with Formula 1 legend Jackie Stewart.

But the film’s backers threatened to pull out if he did and, faced with the choice of a day driving the car in the race or a whole summer doing it for the film, chose the latter option.

By that time, he’d already picked up his only Oscar nomination, for 1966’s The Sand Pebbles, though many feel his role as the French prisoner on Devil’s Island in 1973’s Papillon was worthy of another nod.

That, plus The Towering Inferno the next year, made Steve the world’s highest-paid actor, but he’d had enough, and spent the next four years focusing on motorcycle racing.

He came back to Hollywood, making three films, but died in 1980 from cancer, probably caused by removing asbestos from pipes while in the Marines.

He’d travelled to Mexico for experimental treatment and died of a heart attack after surgery.

He was just 50, and had made fewer than 30 movies.

But that was more than enough to secure the title of the King of Cool.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe