The NHS in Scotland is expecting to lose more than 500 doctors this year as more qualified practitioners move abroad.

The figure is revealed in the General Medical Council’s log of applications from doctors looking for references to work abroad.

The GMC expects to issue at least 520 certificates in 2019 – up from 346 in 2013, 365 in 2017 and 492 last year.

The final number may be even higher as some countries do not ask for GMC reference certificates.

Last week it emerged that a department at Glasgow’s Queen Elizabeth University Hospital is under threat because there are not enough doctors to care for patients.

The GMC has placed the hospital’s internal medicine department – which has 93 junior medics – under a programme of stringent inspections in an effort to improve standards.

Meanwhile, last month a report from Audit Scotland revealed that a £7.5 million NHS recruitment campaign aimed at bolstering GP numbers resulted in only 39 additional doctors being hired.

Worried doctors’ leaders predict the staffing crisis will only worsen.

Professor Irfan Ahmed, a leading surgeon and surgical trainer at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, said: “The plain fact is that the NHS is not looking after doctors.

“This figure of 500 is likely to be much higher because some countries, such as those in the Middle East and the USA, do not look for references as they can check them out on the GMC’s website.

“A Career Destination report by the UK Foundation Programme has already revealed that less than half of junior doctors in their second year of training did not enter higher training posts.

Professor Ahmed, whose son, also a doctor, is now studying in the US, said: “Thousands of doctors quit the NHS entirely.

“They either emigrate or move out of medicine and surgery completely. We are hitting possibly the biggest crisis ever to face NHS staffing.

“Doctors are undervalued, uncared for and left to feel very much on their own in a service which was once the envy of the world.

“Previously, they were cared for, valued and generally happy and satisfied with their work and training.

“They knew they would work long hours but were appreciated and part of a team and were provided mentorship by senior colleagues. They had a sense of belonging to their healthcare service. We do not look after our younger generation of doctors well enough and we should not be surprised that they seek jobs elsewhere.”

Last week, a conference on doctors and stress at the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow heard that one in four doctors in training and one in five senior staff now reported feeling burnt out.

Professor Jackie Taylor, president of the college, said: “The workforce challenges facing the NHS in Scotland are now the greatest current threat to the provision of quality health care.

“We need to improve doctors’ working conditions as a matter of urgency if we’re to reduce stress and burnout.

“We need health boards to ensure that they do everything possible to fill vacant positons quickly, as well as implementing simple actions locally, such as ensuring that all doctors have working IT systems, proper rest facilities and access to adequate food and drink when working shifts.

“It’s only by combating all of these pressures together can we ensure that we attract and retain a world-class workforce across our NHS.”

Scottish BMA junior doctors’ leader Lewis Hughes said hospitals were failing to look after and properly mentor their young staff.

He said: “We ask a lot of 23-year-old new doctors. They do jobs no one else is doing at that age – dealing with life and death and people at their sickest.

“They are often young people who have moved hundreds of miles from families. But loyalty is stretched so far and you can hardly blame some for taking jobs abroad where they are valued more.”

Health Secretary Jeane Freeman said: “We highly value our health workforce which is why we are committed to improving the working lives of our staff by taking action on issues like pay, terms and conditions.

“We will continue to work closely with BMA Scotland to identify what further measures can be taken.”

Junior doc blames US move on lack of support

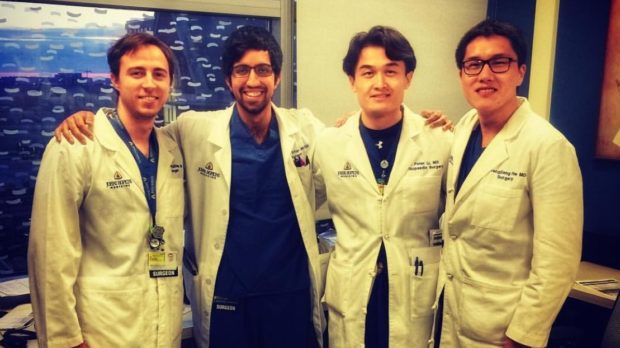

Dr Ahmer Irfan, 26, gave up his surgical training post in the UK to study in the USA because he felt training was less supported here.

The junior doctor said he left his job at Queen Elizabeth University Hospital in Glasgow due to a lack of support and poor morale.

“There has been a loss of morale among juniors and a greater feeling of isolation in the NHS,” said the medic, from Aberdeen.

“You feel more unsupported and unappreciated in the NHS whereas in the USA you are welcomed and your training is valued. Encouragement is obvious and they push me to succeed and improve. I’m not the only UK medical graduate now working in the USA. Several others are training here.”

Ahmer is now working at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. He competed with an international pool of doctors for a training job at the hospital.

“I intend to come back to the UK after training but haven’t made up my mind about my long-term career,” he added.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe