IT was a mission to restore British pride that owed its very being to Scotland.

When Sir Ernest Shackleton set off on his Endurance expedition in 1914 he called it the “last great Polar journey that can be made”. His plan was to cross the Antarctic continent from coast to coast.

After being beaten to the conquests of both Poles, he was determined to make the crossing, saying: “I feel it is up to the British nation to accomplish this.”

But the ship may never have sailed had Dundonian jute baron Sir James Caird not contributed almost half the cost, more than £2m in today’s money. And Scots peppered the crew of the Endurance which was to come to grief, caught and then crushed by the unforgiving Antarctic ice floes.

Now an exhibition at the National Library of Scotland is marking the centenary of Shackleton’s return to the UK following the expedition, which was ill-fated but filled with remarkable heroism and dedication.

Early in 1915, the Endurance became trapped in the ice and sank ten months later.

The crew had already abandoned the ship to live on the floating ice and, in April 1916, set off in three small boats. They eventually reached Elephant Island and Shackleton and five of the crew went to find help, spending 16 days crossing 800 miles of ocean to reach South Georgia. Not one soul was lost on Shackleton’s Weddell Sea voyage as he and the men aboard all battled back to safety.

Enduring Eye shows their struggles to survive through newly-digitised images processed from the 100-year-old glass plate and celluloid negatives of celebrated photographer Frank Hurley. He dived into the freezing waters as the ship was sinking in the ice to rescue them and they’ve been stored at the Royal Geographical Society for more than 80 years.

Paula Williams, National Library of Scotland curator, said: “The stunning photographs in this exhibition tell an amazing story of human daring in the most hostile of circumstances.”

Enduring Eye: The Antarctic legacy of Sir Ernest Shackleton and Frank Hurley is at the National Library of Scotland until November 12.

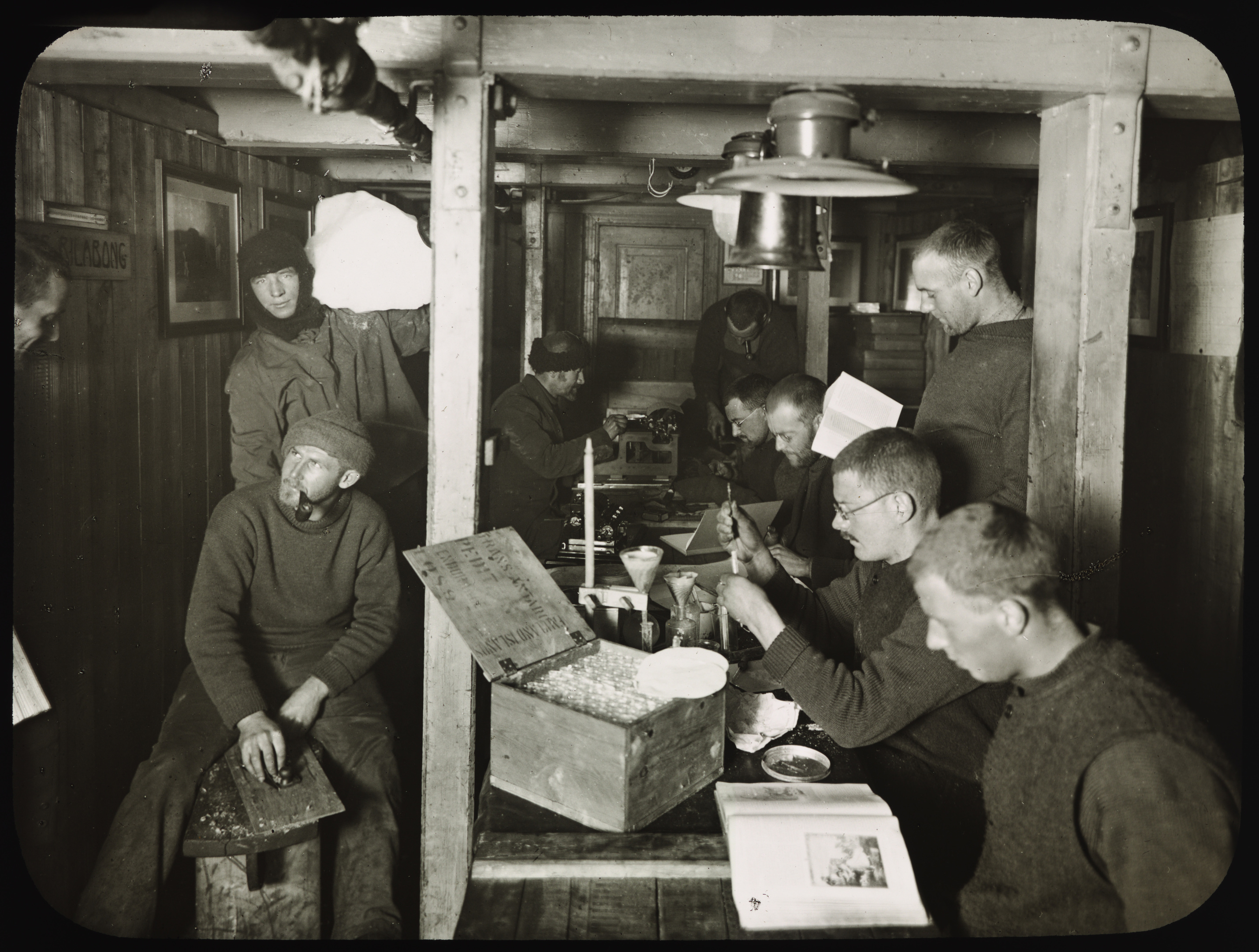

Here, historian Meredith Hooper, who has researched and curated the exhibition, tells us the amazing stories behind one of the pictures, called A Winter afternoon in the Ritz.

New secrets in old photo

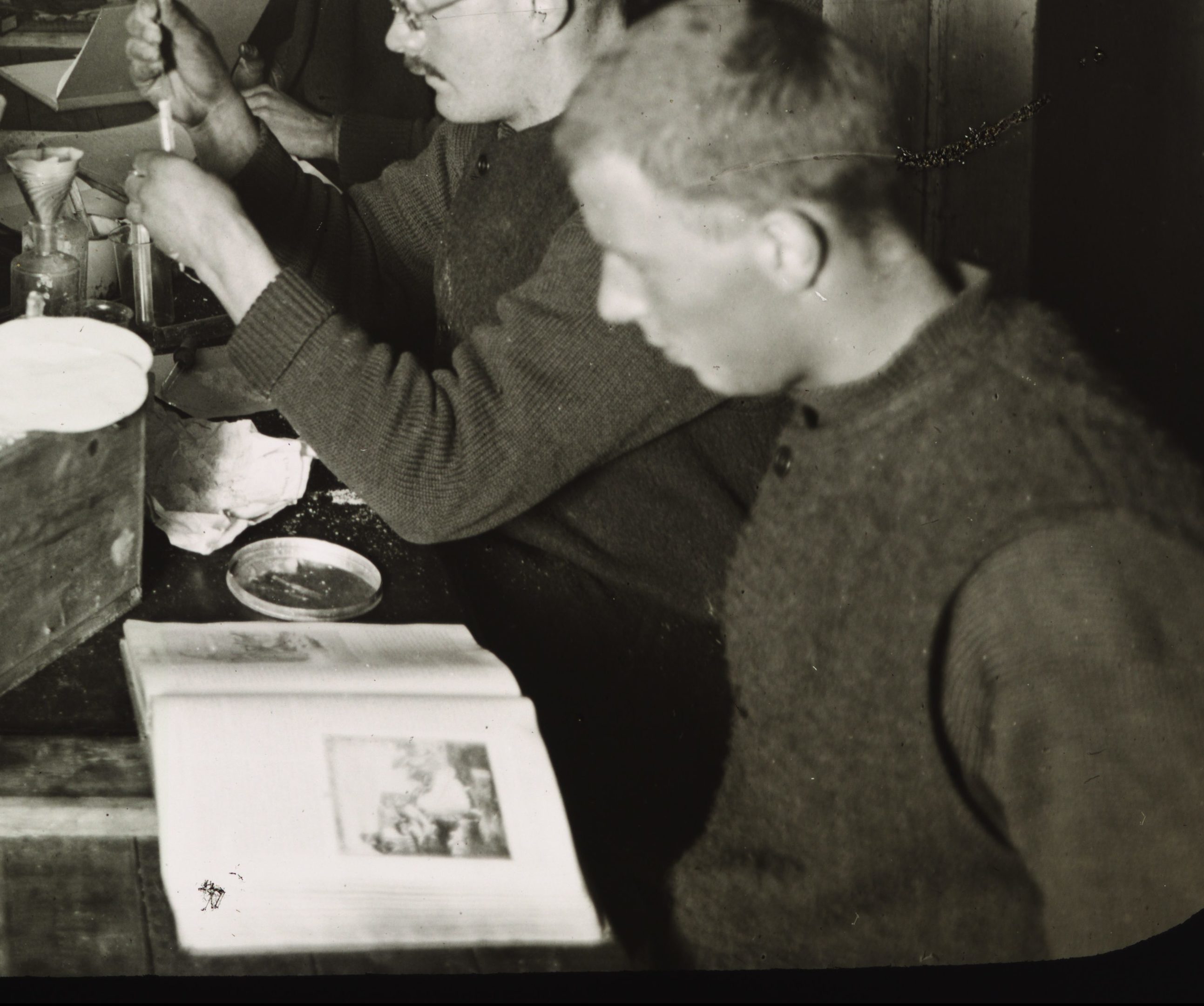

The beauty of having all these images digitised is that we are seeing detail we didn’t know existed. For example surgeon James McIlroy, hadn’t previously been seen in the picture.

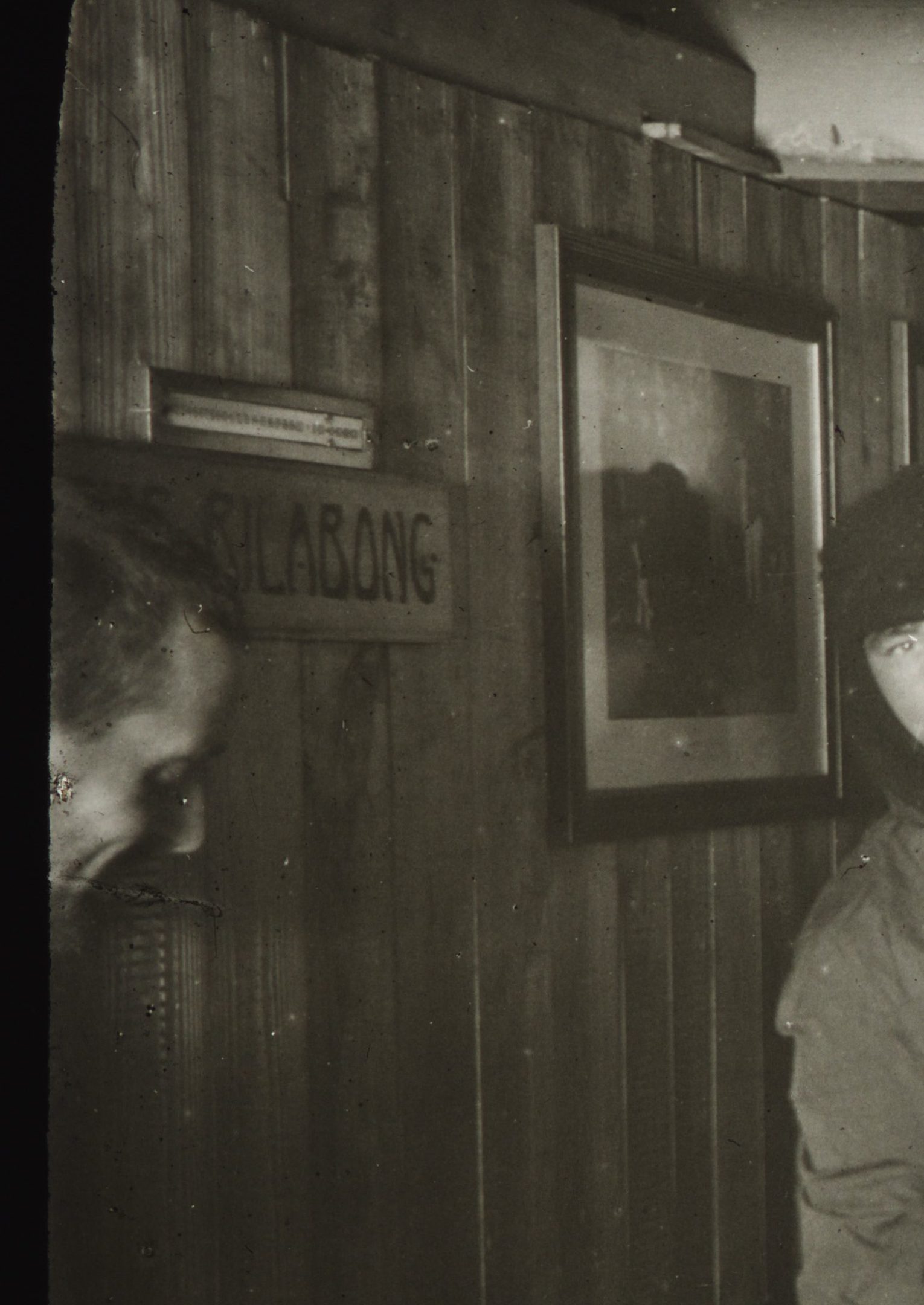

You can just see about see word “Billabong” written on a wooden sign. Each of the 6ft by 6ft cubicles had a name. Frank Hurley managed to get a double cubicle, shared by four, built and, being an Australian he chose a good Aussie name.

Frank was an incredibly good storyteller. Every picture has many layers.

Anyone for a smoke?

Smoking was a big part of life, as we see from First Officer Lionel Greenstreet and his pipe.

Supplies were plentiful at first, but after the crew had been trapped for some time they started running out. By the time they got to Elephant Island, tobacco shortage was one of the greatest hardships. They tried smoking wood shavings and even the stuff used to line boots.

You can see the toll the conditions had taken on Greenstreet’s swollen, frostbitten right hand.

The Ritz? Not exactly

The area shown in this photograph was actually cargo space transformed by Scots carpenter Harry “Chippy” McNish.

The ingenious McNish, who came from Port Glasgow, used wood intended for the hut on the shores of Antarctica. To the sides there are tiny cabins, each for two men.

In the middle is the only common space.

It was jokingly called The Ritz because it was the cramped opposite of the plush London hotel. Living right on top of each other with nowhere else to go must have produced tensions.

Stowaway turns into the iceman

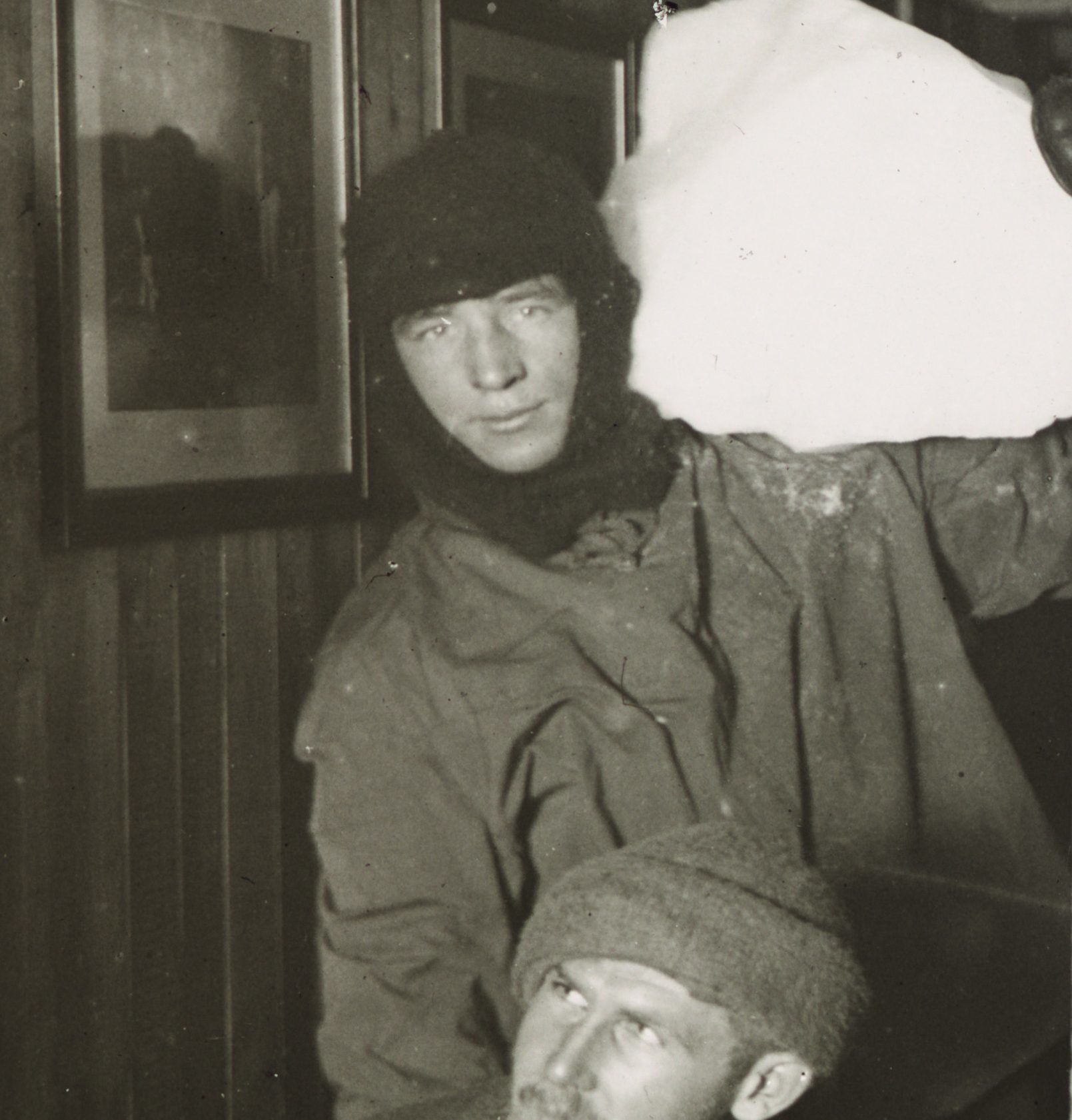

The man with the ice, Perce Blackborow, has a remarkable story.

He was a stowaway who boarded in Buenos Aires. His friend got a last-minute berth but when Blackborow was refused a place because there was no room, he decided he wanted to go on this great adventure anyway.

His friend helped him to hide away. He was found after a couple of days when a hatch was opened and, because it was too late to do anything, he became the steward.

He was young and enthusiastic and became very popular.

Blackborow is carrying ice which would be melted down for water.

The block he’s carrying would have provided enough water for the men for 24 hours.

Busy doing nothing

What the photographer wanted to do was show how everyone was still busily engaged, despite being trapped.

So, you see them reading and conducting scientific experiments – although quite what experiments they could do while stuck in the ice when it’s totally dark outside, I’m really not sure.

It all seems a bit of a fudge, but the intention was to portray an upbeat picture. It’s a bit of expedition propaganda.

The light in the middle was one from an electric system that Hurley had managed to rig up.

Meet the cold cut crew

There was a tradition on Antarctic ships called the winter madness where you’d shave all your hair off.

It’s so strange, given that your hair keeps you warm, to cut it off in the middle of winter in the southern hemisphere.

Glasgow-born geologist James Wordie was one of three scientists. His hair is growing back, so my guess is that the photo dates from about July 1915.

Greenstreet and Thomas Orde-Lees behind him have hats, probably to keep their heads warm until their hair grows back.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe