The curtains have been going up on pantomimes all over Scotland for nearly 150 years – and today they remain as popular as ever.

When the goodies and baddies step out on to the footlights they get the same cheers, hisses and boos as they have done since the first pantos hit the stage back in 1870.

And as theatres fill up this festive season, audiences of all generations, from toddlers to grandparents, are showing no sign of giving up on the Dame and Buttons.

Scotland’s rich pantomime heritage is preserved in the University of Glasgow’s Scottish Theatre Archives – a rare collection of show bills, programmes and photographs.

“We have a unique record of Scottish pantomime dating back to the 1930s, with more than 70,000 items from all the major theatres: Ayr, Dundee, Edinburgh, Inverness, Aberdeen and Glasgow among others,” said Claire McKendrick, chief library assistant in charge of special collections at the University of Glasgow.

Tucked away in climate-controlled archives, the records offer a fascinating glimpse of panto then and now. The stars through the ages are caught on camera and billed on posters, a line-up of greats that includes Stanley Baxter, Jack Milroy, Mary Lee, Johnny Beattie, Gregor Fisher and Rikki Fulton.

Baxter, famous for his elegant grand dames, and Angus Lennie, who played Archie Ives in The Great Escape, are pictured as the Jelly Tots, the two Ugly Sisters in a 1979 production of Cinderella at the King’s Theatre Edinburgh.

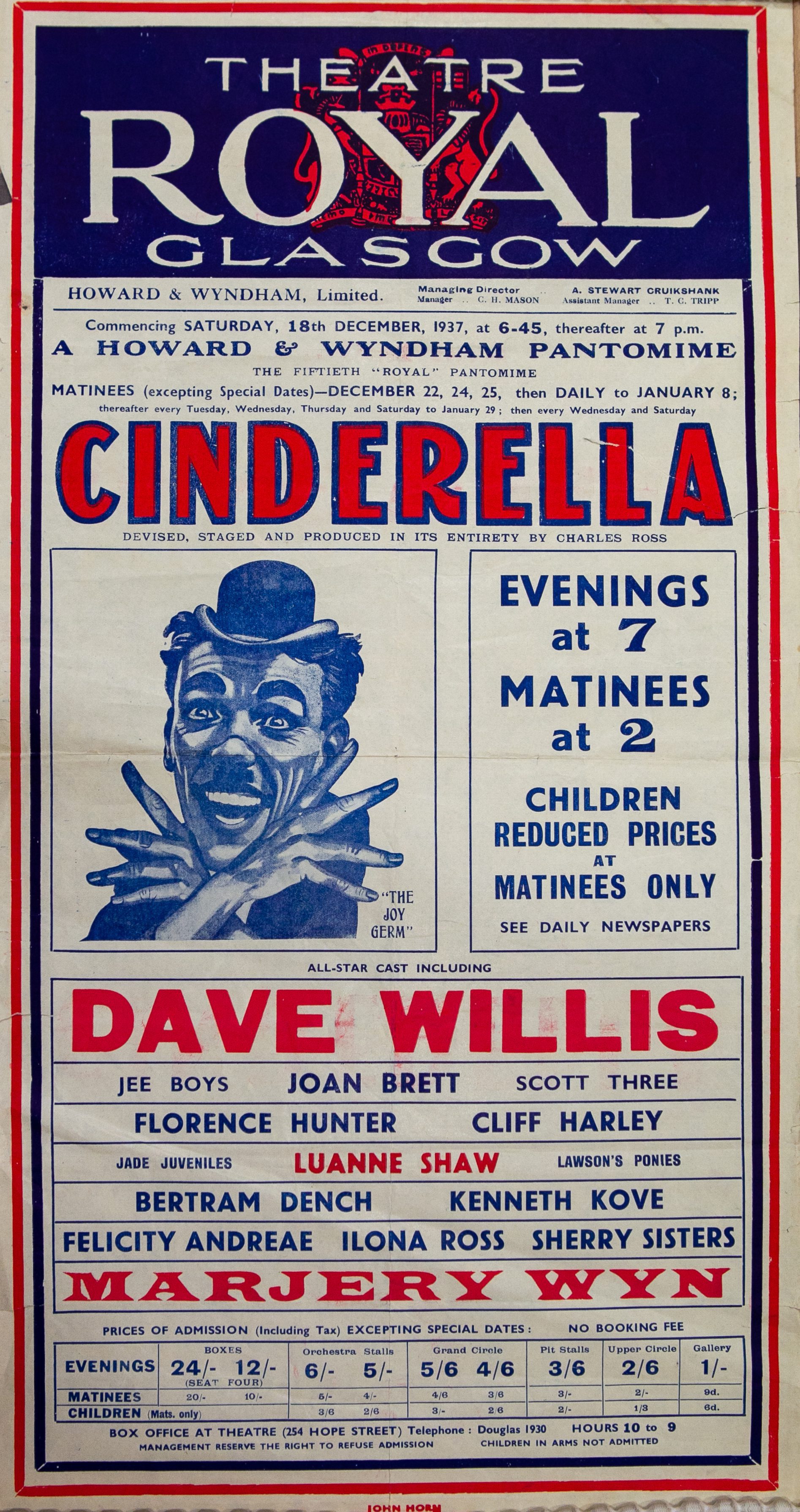

Going further back, a show bill from 1937 announces Dave Willis – a huge star in the heyday of panto between the wars – is to star in Cinderella at the Theatre Royal in Glasgow, while a photo of a knockabout comic scene from a 1947 production of Wee MacGregor could have been taken yesterday. “People love the familiarity of panto – the stories and the characters,” said Dr Paul Maloney of Queens University Belfast, a specialist in pantomime, music hall and Scottish theatre.

“In Scotland, panto developed out of the mid-19th Century music hall tradition, with many elements we’d recognise today – a romantic leading couple, gripping spectacle with colourful costumes and coloured lights, and audience participation.”

Earlier forms of pantomime were first put on in London by the clown Grimaldi, but modern audiences would struggle to recognise them as these “harlequinades” owed more to the Italian tradition of “commedia dell’arte” and used mime, chase scenes and acrobatics, with the folk tale or pantomime only playing a minor part.

By the 1870s, an influx of comic stars from music hall meant the panto as we know it, featuring well-loved stories such as Dick Whittington and Jack the Giant Killer, had taken centre stage.

But we have Scotland to thank for the Dame invented by music hall’s “Scotch comics”, men who donned a frock to play a man-hungry widow to general hilarity.

“You can get great comic mileage out of a big, rough masculine man playing a woman, but there are different ways of playing the Dame,” said Dr Maloney.

“Jack Milroy and Johnny Beattie played a rough man clowning about in a dress, tripping over their high heels, while Stanley Baxter was more of an observational comic doing an impersonation of a Kelvinside lady.”

The Scots comic also brought to panto the tradition of coming down to the footlights, working in jokes about contemporary events, and interacting with the audience in their own language and accent.

“The physical, knockabout slapstick comedy that we associate with panto came straight out of the music hall in Scotland,” added Dr Maloney.

“By the 1920s and 1930s, we had a fantastic generation of comedians in panto – Will Fyffe, Harry Gordon and Dave Willis. Pantos became so popular, they would run from December to May with topical hit songs, dancing and big bands.”

While the genre has not changed in some ways, it is at its best when it keeps abreast of changing times.

“Gags are updated every year as panto has to be topical, with hit songs and cultural and political references that are recognisable,” said Dr Maloney.

“There are always a couple of silly characters, knockabout and toilet humour that small children find hilarious, and some mild innuendo for the older generations that goes over the kids’ heads.

“But there’s also pathos and a moral story where good triumphs.Spectacle is important in panto as young children are susceptible to the magic of stage illusion – the lights, glitter, the flying cars and carpets.”

While panto has stayed true to its Victorian origins, it has also changed with the times in Scotland – and for the better, according to Johnny McKnight, a leading light who both plays the Dame and writes pantos.

“Comedy has changed to become more politically aware, and panto reflects that,” said Johnny, who has written Cinderfella with an all-female cast for this year’s production at The Tron in Glasgow, and who is also playing the Dame in Rapunzel at the Macrobert Arts Centre in Stirling.

“Panto has been a boys’ game for too long but I’m glad to say we now have Elaine C Smith as a Dame, and at the Macrobert the cast is gender-split.

“In the past it was mostly the men who were the funny ones and that’s changing.”

One of the most striking changes is that the romantic hero – the principal boy – is no longer played by a woman in short coat and tights, a strong tradition in Victorian and Edwardian times when it was considered risqué to see a woman’s legs.

Despite these changes, Johnny believes Scottish panto’s success is due to sticking to its music hall roots, and as a result is superior to productions south of the border.

“Their panto is much bluer, adult comedy with innuendos you wouldn’t want to explain to your kids.

“We have stayed truer to our panto tradition – it’s all about telling a very moral fairy tale where good conquers evil.

“Panto is steeped in working class tradition, where the little man wins out over the big man and brings down the system.

“It’s a wonderful tradition if everyone on stage respects it. Panto has to be magical, thrilling and brilliant, and I’m lucky to follow in the footsteps of great Scottish panto comedians such as Stanley Baxter, Johnny Beattie, The Krankies, Gerard Kelly and Elaine C Smith – all legends.”

Today, the enduring appeal of the panto is that three generations of a family can enjoy a show together – an otherwise rare happening in an age of smartphones, tablets and digital streaming.

“It’s the one time many people go to the theatre in a year and they often go in groups so it’s a communal experience,” said Dr Maloney.

“Panto is big business and is holding its own where other types of theatre other than big musicals struggle to survive.”

No dames, just women in Cinderfella

Turning traditional panto convention on its head, this year’s show at the Tron Theatre in Glasgow boasts an all-female cast.

Doing away with Dames, Cinderfella features female actors dressing as men to play the wicked stepbrothers and a princess rather than a prince hosting the ball.

Written by Johnny McKnight, who has been penning the boutique theatre’s pantomimes for years, it follows on from last year’s Mammy Goose panto, which portrayed a tale of same-sex love between two heroes.

Speaking to the BBC last week, McKnight said: “Even though panto should be daft and silly, I still believe there should be equality.

“It would be great if more female comedians were celebrated and given the stability of work as a lot of men have been afforded for hundreds of years. And if that pushes a conversation a bit further then great.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley