On Monday, 1,956 days after it happened, 60 seconds of silence opened the fatal accident inquiry into the Clutha helicopter crash.

A Police Scotland helicopter ran out of fuel and fell 600ft through the roof of the busy pub at 10.22pm on November 29, 2013, claiming the lives of seven people, who had been in the bar. The pilot and two police officers on board also died.

Sheriff Principal Craig Turnbull, who is leading the inquiry at a temporary court set up at Hampden Park, and the Crown Office, say the inquiry will not lead to any criminal proceedings. However, recommendations will be made to ensure every lesson can be learned. The sheriff will examine each of the deaths and the cause of the crash in detail and, in particular, scrutinise the fuel management systems and the actions of the pilot.

The investigation will be “inquisitorial, not adversarial” and is expected to hear from 57 witnesses after police took more than 2,000 statements. Their evidence will be heard by 14 legal teams and the Crown has around 1,400 productions.

The inquiry is expected to last until August at the earliest, but evidence will not be heard every day. It resumes on Wednesday.

Here, we look back at the first week’s evidence.

The Flight

The inquiry heard how the Police Scotland helicopter left Glasgow at 8.44pm on the night of the crash, reaching Dalkeith, in Midlothian, an hour later.

It carried out a surveillance mission in Bargeddie, Lanarkshire, at 10.14pm and then Uddingston, before crashing on the Clydeside at 10.22pm when both engines flamed out.

The inquiry heard pilot David Traill had turned off the pumps for the main fuel tank somewhere between Dalkeith and Bothwell.

A special report in October 2015, by the Air Accidents Investigations Branch (AAIB) found the two fuel supply switches were off when the helicopter crashed. One fuel tank was empty, a second contained less than half a litre and a third contained 75 litres but the pumps to take the fuel to the other tanks were off. It is not clear why. Nor is it clear why he did not attempt to land or make mayday calls in response to five low-fuel alerts.

Marcus Cook, senior inspector at the AAIB, told the inquiry he would have expected the pilot to make mayday calls “long before” the crash.

He confirmed there had been five low fuel alerts during the flight and agreed ignoring them would be “downright dangerous”.

Meanwhile, it was claimed a mistake in a maintenance manual may have misled Mr Traill in the flight’s final, critical moments.

Donald Findlay QC, representing the family of victim Robert Jenkins, said the pilot could have been “dangerously misled” by the mistake, beleiving he had longer to react than he had.

Marcus Cook, senior inspector at the AAIB said the manual was wrong to say there would be three to four minutes between one engine flaming out and then the other. It should have read three to four kgs of fuel and has since been changed.

He said: “The maintenance manual is incorrect. It would be three to four kilograms – hence about a minute.”

Mr Findlay asked: “If the pilot Captain Traill knew about the gap and understood it to be three or four minutes, he had been badly misled?

“If he knew,” Mr Cook replied.

“And dangerously misled,” Mr Findlay added.

Mr Cook said: “Your words.”

Mr Findlay asked: “Is there anything wrong with my words?”

“No,” Mr Cook replied.

He said the pilot would have had 40 seconds to react when the first engine flamed out.

When the second engine followed, there would have been less than 10 seconds to react.

He said there were indications the pilot attempted to begin a landing manoeuvre but in vain.

Mr Cook said the first low-fuel light, of five fuel warnings, would have come on when the pilot was around Bothwell, 11 miles from Glasgow city centre. He would have been expected to land within 10 minutes.

The inquiry heard the AAIB report indicates the helicopter then went to Uddingston and Bargeddie.

Mr Findlay asked: “Why would anyone with the warnings and the knowledge of the amount of fuel on board then carry out an operation at Uddingston, let alone going on to Bargeddie, in that situation?

Mr Cook said: “I’ve absolutely no idea,” before Mr Findlay asked how the crash happened.

Mr Cook said: “Unfortunately we could not come to a positive conclusion apart from not landing in 10 minutes.”

The Victims

More than 100 people were watching a ska band at the Clutha Vaults pub when the helicopter, returning to its base on the banks of the River Clyde, crashed through the roof.

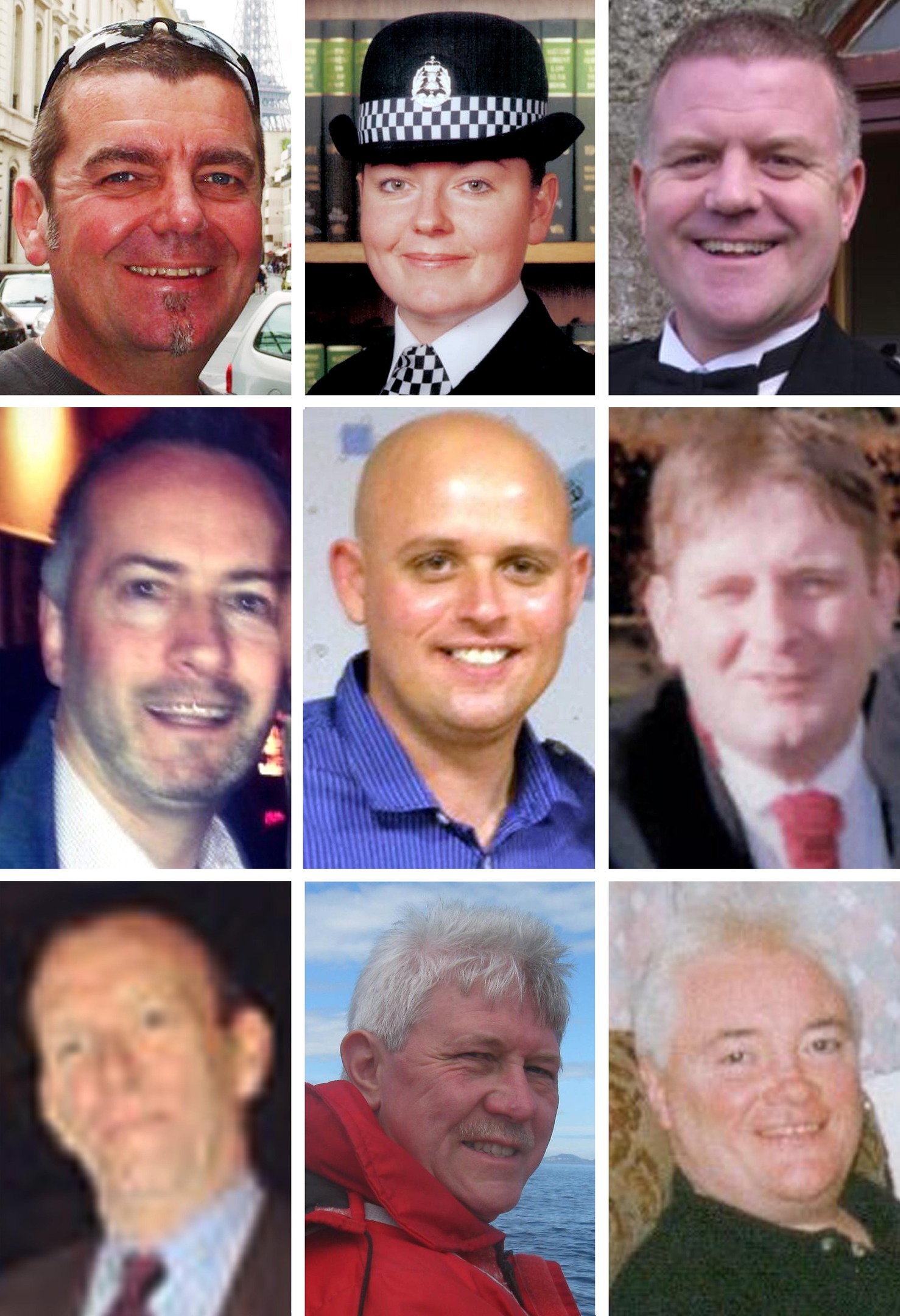

On the night of the crash, Clutha customers Mark O’Prey, 44, a window cleaner; Gary Arthur, 48, a sales adviser; John McGarrigle, 58, a writer; Colin Gibson, 33, an immigration officer; Robert Jenkins, 61, a customer service adviser; Samuel McGhee, 56, a car wash maintenance worker; and Joe Cusker, 59, a retired housing manager, died along with pilot David Traill, 51, and crew, police officers Tony Collins, 43, and Kirsty Nelis, 36.

Personal statements about some of those who died were read out in tribute.

A tribute was read for victim Robert Jenkins, “a well-read film buff,” which told of the pain his partner, Mary Kavanagh, suffered after being at the pub on the fateful night.

It said: “They had only been in the bar for 40 minutes when tragedy struck.

“All Mary wants to know is why she went in that bar with the man she was to spend the rest of her life with, and came out alone.”

Kerry McGhee described her father, Samuel McGhee, as a hard worker who was “very sociable” with “many friends”.

A statement from Colin Gibson’s family said: “If you were lucky enough to meet him, you knew you he left a lasting impression.”

The sisters of Gary Arthur told the inquiry in a statement: “Nothing will ever bring our brother back but hopefully we will finally be given the chance to find closure.

“We want to remember Gary as a much-loved person and not just a victim of the Clutha.”

Mark O’Prey’s father, Ian, described his son as “wonderful” adding: “I had

three children, now I only have two daughters.

“He was a wonderful son who loved life and lived it to the full.

“I only hope this hearing arrives at some truth and I wish it well.”

The inquiry also heard how the victims died, most from head or neck injuries caused by the crash which left several of them trapped in the rubble and wreckage. Several were alive when found by emergency crews but later died.

The Witnesses

The first person to give evidence was Andrew Bergin, 30, a lawyer, from Airdrie.

He was on the Clydeside on the night of the crash and told the inquiry: “When I first started to watch there was nothing particular about it.

“It made what I can only describe as a spluttering noise. It wasn’t any lower than I would have seen it before.

“The tail of the helicopter dipped and pointed to the ground. Simultaneously, the light on the helicopter went out. It seemed to me that the rotor stopped spinning. It was still turning, but not under power. It seemed to immediately lose height as soon as the spluttering occurred. Everything happened more or less at the same time.”

Another witness, Brian Stewart, was on Dyer’s Lane, just under a mile from the Clutha.

The 40-year-old electric production operator, from Glasgow, said: “I had heard a noise coming from it. It was kind of like when you stall your car when you have it in the wrong gear and it struggles, kind of like that.

“I noticed the flashing light underneath, it seemed to be slowing down as it fell out of the sky.

“It happened a couple of times, then it fell behind the building in front of me on Turnbull Street.”

Ernest Doherty heard a sound from above that grabbed his attention. The 64-year-old from South Lanarkshire said: “It made a sound like an old car trying to start, but trying to start 1,000 times louder.

“As I looked up above the buildings of the Briggait, I saw the helicopter come down, passing the church.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe