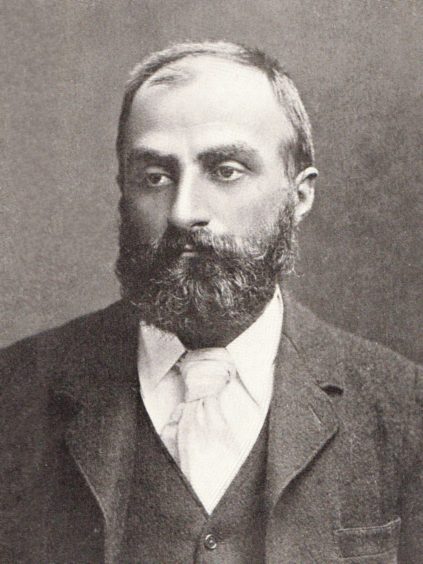

He is a forgotten hero of the deadly Antarctic expeditions of the early 20th Century.

Before Shackleton and Scott, there was William Speirs Bruce, an Edinburgh scientist with a personality “as prickly as a thistle”.

By 1900, he had been to the North Pole three times and the South Pole once, and in 1902 he led a Scottish team to the Antarctic, where he set up a weather station on the South Orkney Islands that is still in use today. Yet he was snubbed for a prestigious Polar Medal and became a broken, bitter man, with his exploits all but overlooked by the time of his death in 1921, aged just 54.

Now, historian and maritime enthusiast Nicola Wright is mounting a drive to win Bruce his rightful place as one of the great Scots of the Antarctic.

She believes the reason his name and achievements have been lost to history is because his expedition was so successful.

“No one died a tragic death, no one became stuck – even the dog, Russ, survived. The public was hungry for tales of disaster and heroism so, because this one was a success, it wasn’t a great story to tell,” explained Nicola.

“He was a really difficult figure. He was awkward and rubbed people up the wrong way. Unlike Shackleton, who was a great charmer and entertainer, Bruce didn’t like crowds or public speaking. He was a scientist who wanted to produce volumes of research, and that’s what he did. It’s been suggested he might have been on the autism spectrum, which fits in with his personality.”

Born in London to a Scottish physician father and Welsh mother, Bruce was studying medicine when he visited Edinburgh in 1887 for two vacation courses covering subjects such as botany and geology. Falling in love with the city and the course work, he switched his studies permanently to the Scottish capital.

In 1892, he was recommended for the Dundee Whaling Expedition to the Antarctic, the first of a series of trips he made to the North and South Poles over the next decade.

Bruce clashed with The Royal Geographic Society’s Sir Clements Markham, who was planning the National Antarctic Expedition, which would eventually become the Discovery voyage. Feeling snubbed that he wasn’t chosen to be part of the staff, despite having more experience than Robert Falcon Scott, Bruce instead organised a Scottish National Antarctic Expedition, which further raised the ire of Markham.

Nicola continued: “The Royal Scottish Geographic Society provided funds, as did the Coats, a wealthy manufacturing family in Paisley. He also received money from the Scottish public. The snub had fuelled his nationalism and it caught the people’s attention.”

He set sail from Troon on November, 1902, on the Scotia, a Norwegian whaler he’d transformed into a research ship.

“He took with him six scientists – five of whom were Scottish – and a 26-man all-Scottish crew,” Nicola said. “They all got on really well. There were no fall-outs, from what I can gather. Nobody went mad. One person died, the engineer, but it was from heart failure rather than a tragic accident. Again, none of this makes for a juicy story.

“He was at his best in this type of situation. He was known as The Boss and, while everyone agreed Bruce was difficult to get to know, they all really cared about him.”

They set up a permanent weather station on the South Orkney Islands and Bruce reached an agreement for Argentina to control it, which the South American country continues to do today.

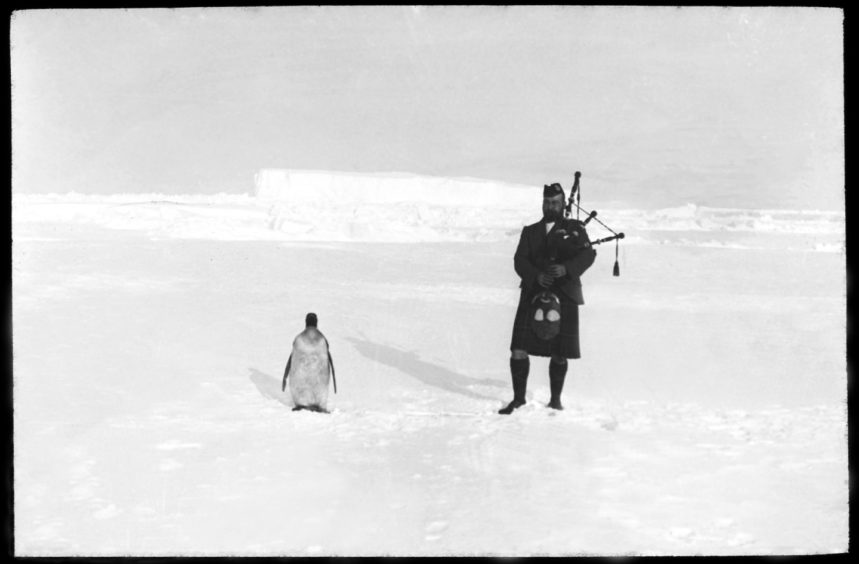

Alongside the weather station, perhaps the most enduring part of the trip comes in the form of a famous photograph, which showed a piper, Gilbert Kerr, in full Highland dress, standing beside a penguin, which had to be tethered to keep it in place for the purposes of the picture.

“The Scotia returned in 1904 and Bruce set up the Scottish Oceanographic Laboratory, a ramshackle building next to the Surgeons’ Hall where he stored the specimens he’d gathered,” Nicola continued. “He hoped to fund another exhibition, but that didn’t happen, and the polar medal snub was a big issue for him.

“The last 10 years of his life were quite sad. He was forced to close the lab because of a lack of money, his marriage broke down, and he had a mental and physical collapse. By the time of his death he was almost a forgotten figure.”

Nicola, who is a professional storyteller in addition to working at the Trinity House Maritime Museum in Leith, hopes to bring Bruce back to public consciousness. She has written a show, Scots In The Antarctic: A Tale With Penguins, Pipers And A Dog Named Russ, which she will perform at the Scottish International Storytelling Festival, which begins this week.

The Edinburgh festival will present a series of live and virtual events between Saturday and Halloween, with a focus on nautical-themed stories to celebrate Scotland’s Year of Coasts and Waters.

Nicola added: “I was asked in February to come up with a show about Bruce, who I wasn’t aware of at the time. He became my lockdown companion and I threw myself into research.

“He was a man ahead of his time. Today we are very much about science and looking at climate change, and that was him all over – he was much more concerned about the science and setting up weather stations than being the first man to plant a flag.

“He was also co-founder of Edinburgh Zoo and founder of the Scottish Ski Club. Scientists respected him, as did fellow explorers, but his personality worked against him and he was forgotten. Hopefully this can be the start of changing that, because he has an important story and is someone who needs to be known.”

More information at sisf.org.uk

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Supplied

© Supplied © Glasgow Digital Library

© Glasgow Digital Library