Have you ever felt like this? “Plain, sky and mountains ray beauty which you feel. You bathe in these spirit-beams, turning round and round, as if warming at a camp fire.

“Presently you lose consciousness of your own separate existence: you blend with the landscape, and become part and parcel of nature.”

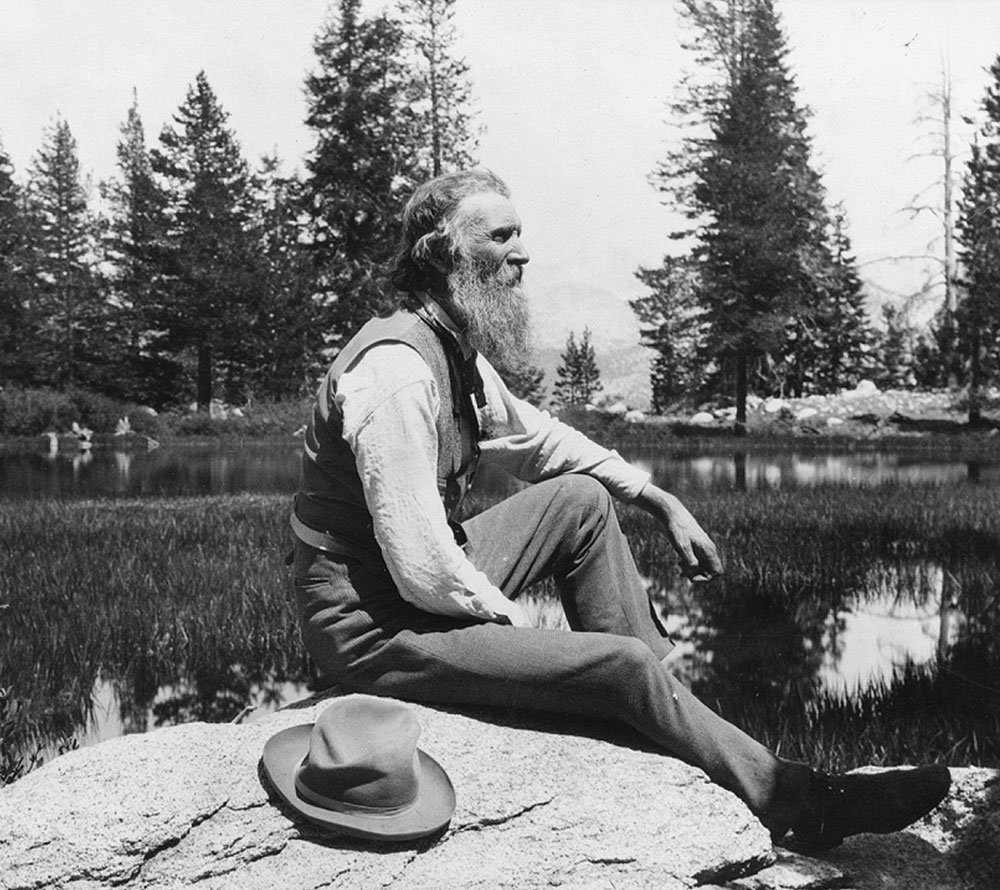

The writer was John Muir, and it’s from an early essay about his first Californian summer.

You can sense the fledgling writer testing his wings.

The writer the world would soon get to know had just announced himself. Suddenly the literature of the American wilderness spoke with a Scottish accent.

I love the sentiment. It’s what I aspire to as a nature writer – to become a part of the landscape and win over nature’s intimacy, so that its secrets become accessible. Certain moments in the wild year seem to assist the process.

The first snow is always a good time. It may have been flirting with the mountain summits since late September or early October, but it’s often November when it finally smoors autumn’s last faltering flames below the treeline.

I love first snow falling in woodland. It has a scent, a taste… rather like the scent and taste of the purest, clearest, spring water.

I have been working this year on the last of a quartet of books about the seasons. The whole project will have taken five years when The Nature of Summer publishes sometime next May or June.

My mindset has been locked into the slow march of the seasons across the face of the land all that time. And, having begun the process with The Nature of Autumn, the first new snow will complete a fascinating circle.

A few years ago, I took part in a series of four television documentaries about Britain’s national parks. Scotland was represented by the Cairngorms. I was asked to say something about the pinewoods and the producer had selected an area of old trees above Glenmore Lodge. I was to be filmed sitting with my back to one of those trees, writing – a thing I have done many, many times. There was one moment when something interesting happened.

They were filming the sequence. I was told I could scribble any old thing, because the camera would not home in on the page. Shame really, as it turned out.

It had snowed. The sun came out. There was a juniper bush a few yards in front of me. I started to watch it and lost track of what the crew was doing. The light was bothering them.

I stared at the juniper. Its light coating of snow started to melt, becoming water again. But at one point the snowflakes collapsed gracefully into something like flowers, then metamorphosed into points of light – the whitest light you have ever seen.

At this point, I turned the page of the notebook in my lap. I started to write with a purpose. My engagement with the juniper bush was total. It was as if nature had tapped me on the shoulder and whispered: “Watch this!”

This is what I wrote:

“Pinewood Hours

“A half-hearted blossom of autumn-into-winter snow time-lapsed open on juniper stems one long pinewood hour while I, seated in the roots of a tree so sure of its history it remembers wolves, did nothing at all but wait for the pinewood to speak. A new hour began in the same old silence after the snow stopped falling and infant winter licked its finger to test the new wind while snared snow-flowers shrank to diamonds of white light.”

That was the pinewood’s gift – that and the new knowledge that pinewood hours take longer.

The great thing about new snow at the end of autumn for a nature writer is you can start to read about the inhabitants of the wood – or wherever – because they start to write their stories in the snow.

Footprints, here walking slowly, here lengthening the stride, here running flat out, here coming to a sudden standstill then sitting – see where the tail wrapped around the hurdies!

A few bloodspots can detain you for hours while you try to reconstruct events.

I lived for a few years in Balquhidder, near a pond with a reed bed that ended in a steep bank. As soon as the snow grew deep enough to sustain a slide, the neighbourhood otters wore a new path from the pond to the top of the bank to the slide. The admirable American nature writer Ernest Thompson Seton was being delighted by them more than 100 years ago. This is from his Wild Animals at Home published in 1913: “…every individual of the species frequents some otter slide.

“This is any convenient steep hill or bank, sloping down into deep water, prepared by much use, and worn into a smooth shoot that becomes especially serviceable when snow or ice are there to act as lightning lubricants.

“And here the otters will meet, old and young, male and female, without any thought but the joy of fun together, and shoot down one after the other, swiftly, and swifter still, as the hill grows smooth with use…and chase each other with little animal gasps of glee, each striving to make the shoot more often and more quickly than the others…”

This, or something very like it, was going on at the Balquhidder pond, although I only ever witnessed its aftermath. But it became clear it was most enthusiastically used under two conditions. One was when a deep snowfall provided optimum sledging. The other was when the first snow came, because the whole concept of sledging had become a novelty all over again for the adults, and an ecstatic discovery for the year’s cubs. And every morning after the night before I would go to the pond and read about it.

And then, there is the story of the short-tailed field vole. There was a day of November in which the first snow came around noon and lasted for two or three hours.

I went out in the last of the light. About two inches of snow lay on the woodland track, much of it pristine.

Suddenly, there at my feet was the most unlikely print in the snow. It was an inch deep, and it was as if someone had made a perfect mould of a short-tailed field vole in silhouette.

There was its nose, an ear, the perfect outline of its head and body, two of the legs, the feet. No footprints led up to it, and none led away from it. But, a yard away, the track of the vole on the run was clearly etched in the snow.

The thing is, I knew exactly what had happened. Once before I saw it happen and it explained to me how a vole body had left its mark.

It was a different track in a different woodland, but I am as certain as I can be that natural history repeated itself.

The first time, it was a day of a big wind and I like walking in woodland. Small bits of trees were all over the track. The air felt mobile, the flotsam of the wood was on the move.

Then something fell from high in a larch tree above me – a dark, tree-coloured blur that was nevertheless not a piece of a tree.

It landed with a soft thud beside my feet. And there it was clearly recognisable as a short-tailed field vole. Not only that, it was very much alive.

At once it sprang away across the track with an extraordinary bound that must have carried it the better part of yard through the air, and it hit the ground running.

It did not slow when it reached the ditch at the edge of the track, nor did it detour round a shallow puddle there, but swam across vigorously, then disappeared among grass and bracken on the far side.

I looked back to the larch tree in time to see a sparrowhawk cast off from a branch, fly fast and low up the track and then swerve away into the depths of the forest.

What had happened was this. The hawk had caught the vole as it crossed the track, and carried it up into the tree. Its grasp on the vole had been imperfect – enough to lift it from the ground but not to carry it far, so it opted to perch and rearrange its grip.

At that point it was disturbed by my sudden appearance, and between that and the movement in the branches caused by the big wind, the vole’s struggles effected the unlikeliest of escapes and it fell to earth. That is my best guess.

And that is also the only circumstance I can think of that explains the soft imprint in the snow, the long gap before the tracks began, and smile of recognition on my face.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe