AS US and British bombs rained down on Baghdad in 2003, Saddam Hussein’s most trusted allies were carrying out one final task for the dictator.

It was deemed vital that his latest novel went to print before his regime in Iraq fell. Appropriately, it was called Get Out, You Damned One!

It is just one of the literary works examined by author Daniel Kalder who discovered that while many dictators have turned their hand to literature, your local bookshop won’t be giving it a shelf any time soon.

By and large, it’s awful.

The multiple works of Hussein, whose first effort, Zabiba And The King, was a romantic tale, are among the most interesting purely because he did not simply use his texts as a way of browbeating a suppressed nation into further compliance.

Daniel, from Dunfermline, Fife, said: “He’s a really interesting case because most dictators publish things with their name on it but didn’t write them.

“Saddam Hussein wrote novels you or I might write. His romance novel was inspired by a very young woman he fell in love with. If you read the book it is about a king who falls in love with a young woman.”

The inspiration for Daniel’s book came around the turn of the century during a time living in Moscow, where the various apartments he moved between had dusty works by Lenin on their shelves.

Switching on his TV, he saw a pink and green monument of a book with the profile of a dictator embossed in gold on its front cover.

It was a broadcast from Turkmenistan and the creation in question was The Book of the Soul, written by Saparmurat Niyazov, the country’s president.

The monument was supposed to open every night to display a different double-page spread of Niyazov’s thoughts but the mechanism had failed, meaning the words of wisdom were never exposed.

Perhaps that is a good thing, given it took Daniel three years to plough through the book itself due to its turgidity. Turkmens had to read the text as part of their driving test before Niyazov’s death in 2006.

Morning

The bud has blossomed; now the rose

Touches the tender violet.

The lily, bent above the grass

By gentle breezes, slumbers not.

The lark, signing its chirping hymn,

Soars high above the clouds;

Meanwhile, the nightingale intones

With sweet, mellifluous sounds:

“Break forth in bloom, Iberian land!

Let joy within you reign.

While you must study, little friend,

And please your motherland!

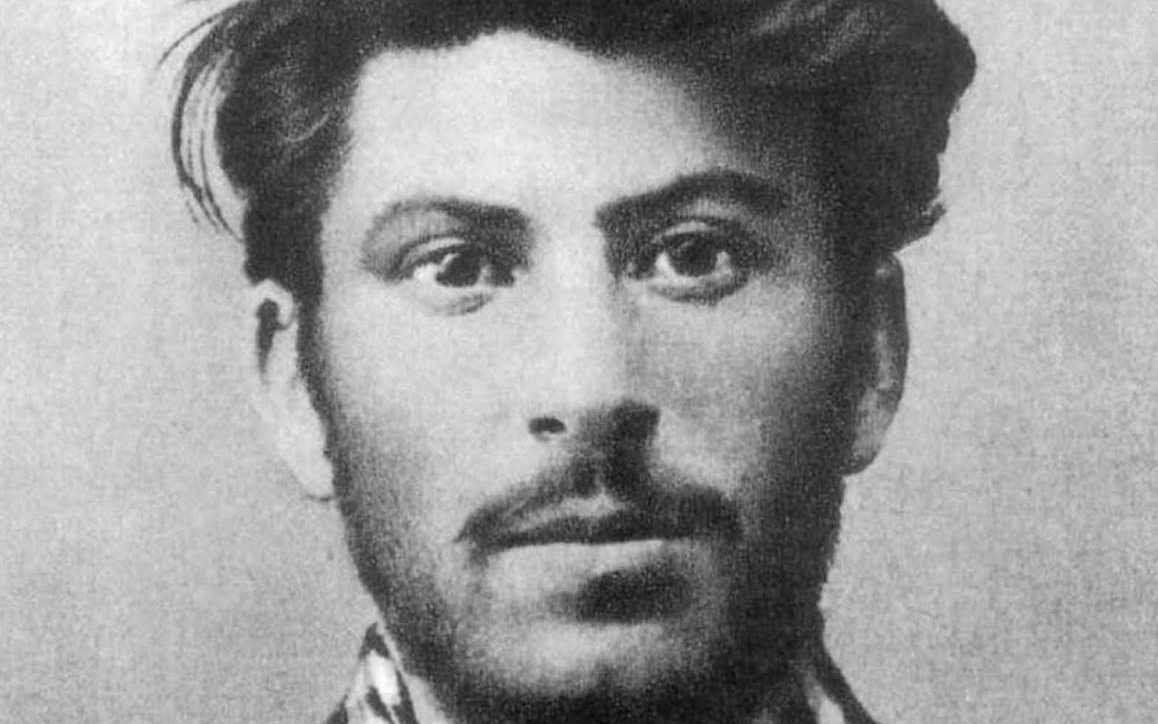

A poem written by a 17-year-old Joseph Stalin in 1895. He grew up to be one of the dominating political figures of the 20th Century, leading the Soviet Union with an iron fist, helping defeat the Nazis while implementing a reign of terror that led to millions of his citizens being killed, sent to camps or dying of starvation

But why do dictators already crushing citizens under an iron rule feel the need to inflict literary misery on their subjects?

Author Daniel said: “There’s propaganda for sure. And these guys have monumental egos. That’s a big part of it. They published these books to prove they were super-geniuses.

“Take the Soviet Union as an example. There was an alternate belief system. They were throwing out bibles and needed something else.

“Then once that precedent had been established, every dictator followed. You had to justify why you were in charge.”

He added: “There’s not a lot of attempt to persuade. A lot of these people had messianic vision. They thought they were going to change the world and they wanted to get their vision across.

“Sometimes it is used to persuade, sometimes it is used to inflict conformity.

“Propaganda is humiliating. If you’re given a book to read that is so dense and impenetrable but you have to pass an exam on it then it leads to cognitive dissonance.”

Some dictators are creative with how they used their works to push their views onto their subjects.

North Korean despot Kim Jong-il, for example, was a big film critic. His effort, The Art of the Cinema, mixes film criticism and technical discussions of filmmaking in a way that, Daniel says, may not be spectacular but does make sense as a “how-to” guide.

In a dark turn, however, he also kidnapped South Korean director Shin Sang-ok and his actor wife Choi Eun-hee in 1978 in an attempt to bolster the film industry.

“Dictators are interested in the arts because they think it’s a way to get the message out but they do it through proxies,” said Daniel.

“Kim Jong-il had trained himself in the art of the cinema. He was interested in the art of illusion. When he became a dictator, he would take the idea of illusion and expand it to the whole country.

“His book gives very specific direction about music being too loud, for example. He thought North Korean movies were terrible and he wanted them to be good and win awards. He had a really big collection of DVDs. He loved James Bond films. He would drink cognac and watch James Bond movies.

“If you think about dictators generally they are very much in the business of illusions.”

Daniel’s favourite literary despot is Mussolini, who began his career as a “skilled journalist” and wrote a war diary. “It started very blustering but the war was very bad, he broke down and wrote about what he saw very honestly,” he said.

“It wasn’t Mein Kampf by Hitler. That is truly shocking. Many people know the name but not many have read it. This is wise. The shocking thing is how open he [Hitler] is.

“He is a mad, raving racist. Stalin was a mass murderer but his writing is very boring.”

The worst writer, in Daniel’s view, was Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, who wrote The Green Book in a bid to rival Mao’s Little Red Book. He even used ECD Iserlohn, a German hockey team he sponsored, in an attempt to promote it round the world.

“When you read the Green Book it is obvious Gaddafi had never read a book,” said Daniel. “Maybe a couple of comics. It’s really bad.”

The phenomenon is not dying out, however, with China’s Xi Jinping, recently made president for life, having written multiple volumes that refer to Mao. Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan also getting in on the act while ruling their respective countries with iron fists.

This was part of the reason Daniel decided to write his book. Another was the idea that many of these dictators started off as marginal figures who unexpectedly rose to positions of extreme power.

He said: “One of the things I was concerned about being forgotten was that these ideas were very seductive. I think it is a very optimistic person that thinks in our world these forces aren’t bubbling under the surface all the time. If we forget what these guys were talking about we won’t recognise the ideas when they reappear, and they will reappear. There’s a degree of cautionary tale.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe