June 6 1944 has gone down in history as D-Day.

But it shouldn’t have.

The Allied invasion of Europe was scheduled for the day before but the weather was unseasonably atrocious.

It was still far from ideal on D-Day but the decision was taken to go as a further postponement would have meant a delay of at least two weeks as the plan needed the phase of the moon, the tides and the times of day to be right.

The risk the Germans would find out about the planned attack was deemed too great to postpone for so long.

However, the story that General Dwight D Eisenhower, in overall command of the invasion, gave the word by saying “OK, let’s go” is entirely apocryphal – “Ike” himself gave five different versions to reporters in the immediate aftermath.

The consequence of the decision to go despite the marginal weather was that most of the men hitting the beaches had suffered horribly with seasickness as their flat-bottomed landing craft rolled in the rough seas.

The success of the beach landings – known as Operation Neptune – depended upon a preceding airborne assault that had the dual aim of both preventing the Germans from rushing reinforcements into Normandy and enabling the Allies to break out of the vulnerable beachhead.

Bridges – some to be captured, others to be destroyed – road crossings, strategic positions and some coastal defences were targeted and the paratroopers and glider troops began hitting the ground just after midnight.

As with most airborne operations, chaos reigned with the troops spread over a wide area but most of the objectives were achieved with the British glider assault at Pegasus Bridge, one of the few parts of the entire plan to go like clockwork.

A force of 181 men of the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry, commanded by Major John Howard, landed in six Horsa gliders, took the bridge’s defenders by surprise and held it until reinforced by the 7th Parachute Battalion.

Interestingly, one of the latter unit’s officers was the actor Richard Todd who, two decades later, would play Howard in the D-Day film The Longest Day, with another actor playing Todd.

Also active that night was the French Resistance who were busy destroying railway lines, locomotives, electrical facilities and telephone and teleprinter cables.

It was later estimated they’d blown up 52 locos and cut the line in more than 500 places, helping to isolate Normandy by June 7.

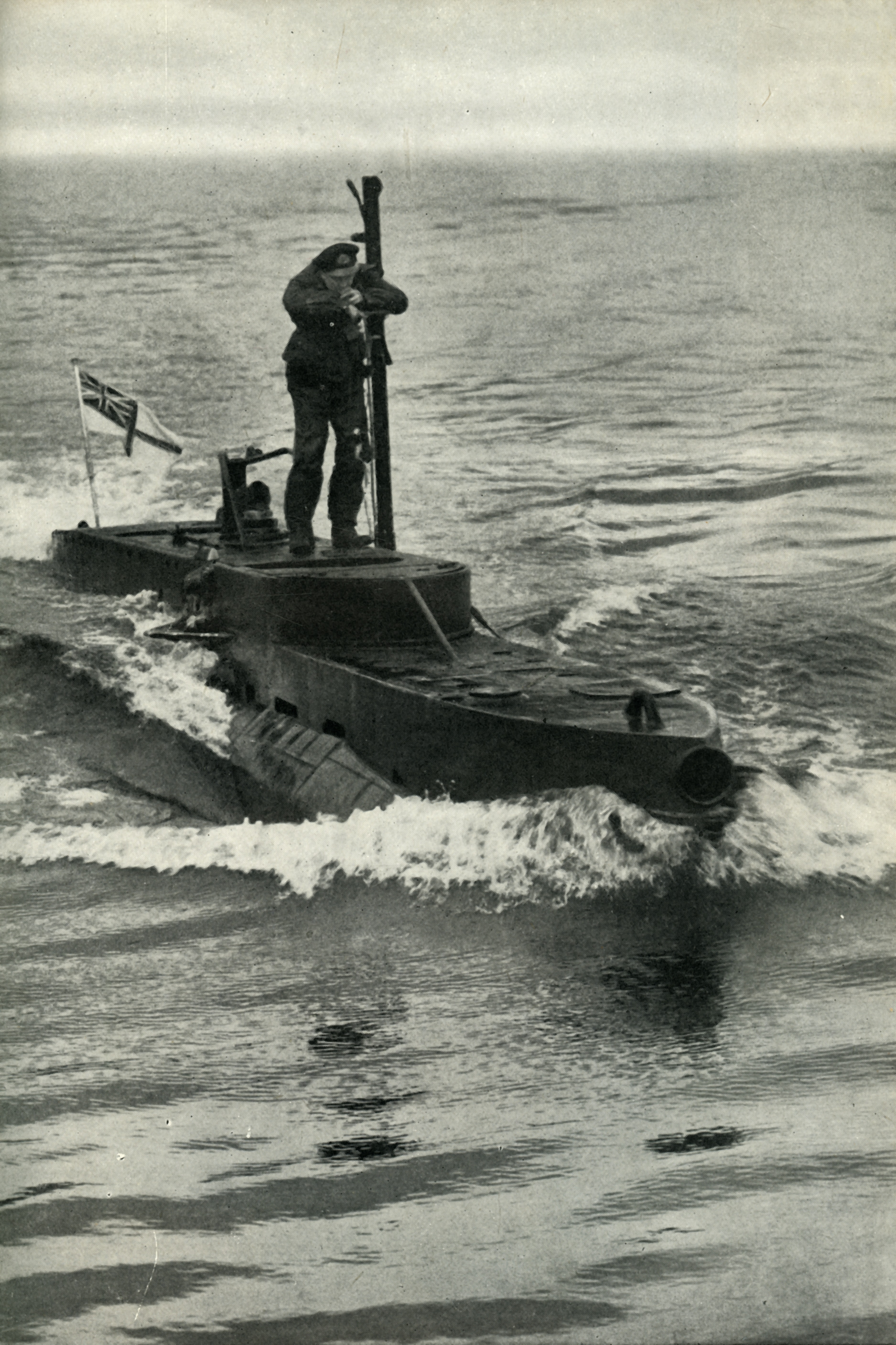

For a small group of men, the invasion had actually begun on June 2.

These were the crews of two “X-Craft” midget submarines who, in Operation Gambit, had lain in wait on the seabed facing Gold and Juno beaches before deploying light beacons to guide the landing craft safely to shore at huge risk to themselves.

They were squarely in the path of the greatest invasion fleet ever assembled – almost 7,000 vessels, including 1,200 warships and more than 4,000 landing craft of various types, some to land troops, others to ferry tanks to the shore, yet others to lay down a rocket barrage to keep the Germans’ heads down.

Heavy bombers plastered the beaches and further inland from midnight onwards and the immense naval bombardment began at 5.45am while it was still dark.

The American landings began at 6.30am, an hour before the British and Canadians went ashore, and on Utah beach strong currents proved to be a positive boon.

They’d swept many of the defences away and pushed the landing craft almost 2,000 yards from their intended landing zone but this proved to be more lightly defended.

As a result, Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr, the President’s eldest son who’d die of a heart attack a month later, made the decision to “start the war from right here”.

To the west, though, the GIs on Omaha beach faced the worst fighting of the invasion. It was the most heavily-defended beach and most of the defences remained intact despite air and naval bombardment.

Those strong currents caused havoc with the landings, scattering the men, and the rough seas meant 27 of the 32 special “swimming” Sherman tanks that had been launched too far from shore were swamped and sank before they could make the beach.

Many of the landing craft beached on sandbars, meaning the men had to wade more than 100m under murderous machine-gun fire. Casualties were horrific.

The initial objectives for Omaha were only achieved on D-Day+3.

On Sword beach, 21 of 25 of those swimming Shermans made it ashore and were instrumental in securing the beachhead, allowing Lord Lovat’s 1st Special Service Brigade to be piped ashore by Lovat’s personal piper.

There was fierce house-to-house fighting here and on Gold and Juno beaches but other specialist tanks, known as Hobart’s Funnies after their creator Major General Percy Hobart, proved their worth.

Some used huge mortars to silence gun emplacements, others filled craters and trenches and “flail” tanks used whirling iron chains to smash a path through minefields.

The Americans had been offered Funnies but were reluctant to use them, a decision they came to regret.

Of the 160,000 troops that landed on D-Day, it’s thought at least 10,000 became casualties with 4,414 confirmed dead.

The Germans lost 1,000 and it’s estimated 3,000 French civilians lost their lives.

The Allied plans called for the capture of four main towns by the end of the day, the beachheads apart from Utah to be linked and a frontline 10 miles from the coast established. Not one of these objectives was achieved.

The five beachheads weren’t connected until June 12 and Caen didn’t fall until the following month but – crucially – Rommel’s theory that the Germans had to “throw the Allies back into the sea” on that first day or face defeat was right and they failed, despite some ferocious counter-attacks.

The end of D-Day didn’t meant the end of fighting in Normandy. In fact, it was some of the most intense combat of the war as the local “bocage” country – small fields surrounded by thick hedges and narrow, sunken lanes – favoured the defenders, who took a heavy toll of Allied forces.

But Hitler’s refusal to let his commanders make tactical withdrawals meant they were eventually encircled, particularly in the Falaise Pocket where the destruction of Army Group B saw half-a-million German men killed or captured.

The survivors retreated over the Seine, ending Operation Overlord.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © STF / AFP / Getty Images

© STF / AFP / Getty Images © The Print Collector / Getty Images

© The Print Collector / Getty Images © Sgt. J Mapham/ IWM via Getty Images

© Sgt. J Mapham/ IWM via Getty Images