They went in search of a new life and found only torture, starvation and, for two of them at least, death.

The dark story of the Greenock Stowaways – a little-known piece of Scottish history – tells of young boys in search of adventure in 1868 and the sadistic sailors whose ship they were unlucky enough to hide on.

Slipping on to The Arran, a cargo ship bound for Quebec from Greenock, seven boys, aged 11 to 22, found themselves at the mercy of a cruel first mate, James Kerr, who would eventually put them barefoot on to ice floes in the Arctic, leading to two deaths.

He was eventually brought to justice but, incredibly, was sentenced to just four months in prison.

The boys’ story is charted by best-selling crime author Denise Mina in acclaimed podcast series Unspeakable Scotland, remembering some of the country’s most significant crimes.

“What’s interesting about the Greenock Stowaways is that we know so little about it today,” said Denise. “This probably stems from the fact that it is so dark people would rather not think about it, and that nothing much came of it in terms of punishments for the perpetrators.”

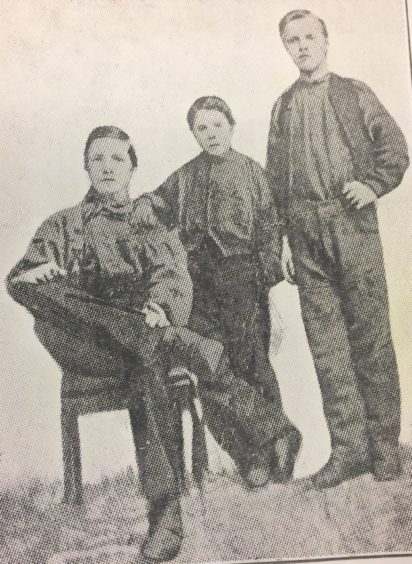

On April 7, 1868, 12-year-old John Paul, 11-year-old Hugh McEwan and 16-year-old James Bryson, along with four other stowaways, were discovered on The Arran. “At the time, stowing away was a pretty commonplace thing,” said the best-selling author.

“It almost became like a work experience for young boys and men – they could work their passage to the colonies and begin a new life.”

At first, the boys were accepted and put to work with the 22 crew members on board, but things soon began to take a more sinister turn.

Having never sailed on ships before, they suffered terrible seasickness and would throw up the food they were given.

Seeing this as a waste, Kerr decided they were to be starved. When the children were caught stealing food from stores, they were flogged with ropes, whips, hooks and plumb irons – heavy instruments used to test the depth of the water.

Kerr raged over the boys, whom he believed were unhygienic and dirty – and would frequently make them strip naked on deck in the freezing conditions, douse them in water and instruct them to scrub each other in front of the crew.

Their skin was so tortured by floggings it was described by a sailor as “red and white tartan”.

Eventually, the boys were put in manacles and starved of all nourishment.

“What we need to understand is that at this time children were treated in ways we now find pretty shocking, and the naval code was governed by strict, physical discipline in order to keep the crew safe and hygienic to save lives,” said Mina, the author of a series of best-selling crime novels.

“However, what was happening on this ship was not normal discipline. There was definitely something wrong with Kerr, and members of the crew would eventually testify to his bizarre cruelty when he faced sentence later in Scotland for his crimes. Today, we would probably describe him as a sadistic paedophile. Back then he was just labelled ‘ferocious’.”

Things finally came to a head for the boys when The Arran became stuck in ice near the coast of Nova Scotia. Deciding they’d had enough of them, Kerr and the captain told the boys they could see village lights in the distance some 15 miles away, and that they were to walk across the ice until they reached land.

Crying and begging to be allowed to stay on board, the boys, some barefoot and in rags so thin their bones could be seen through the material, were forced to walk away from the boat on the ice while Kerr watched from a telescope.

The two 11-year-olds died on the journey. But the others miraculously managed to reach land, using broken ice and a stick as a canoe.

When their tale reached Scotland, there was an outcry and a riotous mob was waiting for The Arran on its return to Greenock that July.

“It was mostly angry mothers, and it took police three hours to get through the crowds to arrest the captain and first mate,” said Denise.

“They were charged with culpable homicide but were not charged at all for the abuse of the children. They were given very short sentences, and there was no real knock-on effect at all.

“There is one slightly happy ending to the tale, however. John Paul eventually returned to Greenock with 12 children, and his descendants still live there. And I’ve heard whenever one of the family moans about being cold, they’re told, ‘Well how do you think poor John Paul felt on the ice?’ It would stop you ever complaining again.”

The Greenock Stowaways, Unspeakable Scotland, available to stream on Acast, Spotify and Apple

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Jonathan Hordle/Shutterstock

© Jonathan Hordle/Shutterstock © Sebastian Grote/AWI via ZUMA Wir

© Sebastian Grote/AWI via ZUMA Wir