Jennifer Lucy Allan is tucked inside a clifftop building. It is the home of the last working foghorn of its kind in Scotland, possibly the world. And it is about to blast a warning across the ocean.

Quickly, she ducks outside, fingers in ears, and waits. Allan is standing on the rocky spur that is Sumburgh Head, the southernmost tip of mainland Shetland, where 300ft below its lighthouse, the wild Atlantic and the North Sea converge.

Suddenly, she is swept up in a tidal wave of sound that rattles her bones and sets her insides abuzz. The moment was years in the making. It came as Allan, a BBC radio presenter and experimental music expert, spent a February living alone at the Shetland lighthouse, propelled there by her passion for the great land-based, foghorns of yesteryear.

Her obsession took her from Scotland to San Francisco, and resulted in a university doctorate, a radio programme, and now a book on the near-obsolete warning systems. But it all began in 2013 during a Foghorn Requiem – an open-air performance of brass bands, ships and foghorns around the cliffs at Souter Point Lighthouse in South Shields. The emotional impact of that concert set her on a quest to understand the foghorn’s power.

Speaking from her London home, Allan – whose 2018 stay on Shetland formed part of her research – revealed: “Souter Point is the harbinger for the book but Sumburgh is at the heart. It is an incredible spot. That stay, that experience and that particular foghorn became the heart of the book.”

The writer, who hosts Radio 3’s Late Junction, explained: “I wanted to be up close to the places, and the machinery and the architecture that I was writing about. Usually I write about sound and music, which you can experience in fairly removed ways. But with this I really wanted to try to understand the landscape and the place in which a foghorn sounded; the way in which keepers would have experienced it.

“I needed to see and hear these things because sound in a landscape – especially a coastal landscape – is really unpredictable and surprising.

“In the UK at least, there aren’t any more huge old 19th Century foghorns in practical use for fog. The ones we hear now are electric.

“The Sumburgh foghorn is still in working order but is sounded for tourists. When it was sounded for me, I experienced some of those acoustic hallucinations. I could hear the sound skipping out over the landscape. It was surprising.

“I wrestled with the question of what makes a sound alive; what makes it present and what makes it in the past; and the way our memories are tied-up with past and present when it comes to sound.

Allan argued Scotland was “much more aware of its coasts and conscious of itself being surrounded by water than England”, and its coastal industries in particular had, she said, “added to the consciousness over the years and the way heritage works today.”

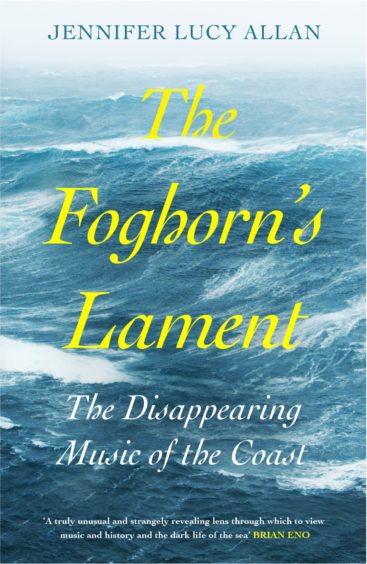

Allan’s debut, The Foghorn’s Lament: The Disappearing Music Of The Coast, is as alluring and haunting as the mammoths of sound themselves.

Reliving the moment she was drawn in by the final requiem note of the Souter Point foghorn, she writes: “When silence settled, I stood frozen to the spot. A lump rose in my throat and my eyes watered. I looked around, and saw tears and glazed looks in the faces of the crowd.

“Something had departed, and we were alone. In that last gasp, the foghorn had articulated not just its own death, but the death of an industry and all that was left behind. This was industrial music, and it meant something – only not in the way I was used to.”

It was a horn unlike any other she had come across as a music journalist; one that could “parp, moan, holler and wail, louder than anything on the coast, big enough to shout-down death.”

She added: “Other big horns exist, but nothing speaks to the sea like the foghorn does, nothing gives such comfort while it warns, and nothing else comes imbued by the colossal weight of life and death, memory and melancholy, that I heard on that day on the cliffs at South Shields.”

She needed to know “the story” of its sound. Immersing herself in archives, including those of Glasgow’s Mitchell Library and the National Records of Scotland in Edinburgh, she gradually unpicked the complex history of the foghorn, first invented in the 1850s by a Scottish emigre Robert Foulis with Scotland (parallel to England) at the cutting edge of foghorn technology thanks to its Stevenson lighthouse dynasty.

Allan links the story of the foghorn to, among others, maritime history, industrialisation, cartography, acoustics, engineering and psycho-geography and modern coastal folklore. She explores rumours that lighthouse keepers’ speech patterns developed around the horn’s blasts; the idea that “sounds of the Second World War battles are still bouncing around in deep sea trenches” and that keepers were paid “fog money” to put up with the din.

And then, there is her voyage on board the Waverley in pursuit of the Clyde’s Cloch Lighthouse where, in 1897, a foghorn was installed to make safe a dangerous bend on the river. She relived how it “swept across the water into Dunoon marauding around the streets and rattling people’s windows like a poltergeist.” The horn sparked so much civic fury, local doctors at a convalescent home penned a protest poem claiming its sound hindered patient recovery.

Her years of foghorn study led her to marvel: “There is no other sound tied so deeply to a type of weather, and no machine sounds quite that massive.”

Allan, who has Scots heritage on her father’s side, is especially interested in how their sounds connect to identity and emotion.

Listening to the horn at Sumburgh it dawned on her: “I had thought of the foghorn as a lonely sound, a big melancholic beast echoing into the vastness of the open sea, often to nobody at all. But it isn’t. This heaving machine is the sound of somebody else, the sound of civilisation and safety…

“I have been thinking, and reading, and writing about this for eight years now. And there is something I still find completely compelling and unresolvable about the meanings of the foghorn and its sound; how it can contains opposites.

“It contains civilisation but it also contains loneliness; it contains life and death. A lament has these ideas of life and death and of remembrance and space and time. It feels very magical to me in a way I have never been able to let go of.”

The history of the foghorn

The invention of the steam-powered foghorn in Canada in the 1850s is credited to Robert Foulis who was born in 1796 in Glasgow.

After training as an engineer he moved to Belfast where he met his first wife, Elizabeth Leatham. Tragically she died in childbirth in 1817 and Foulis struck out for a new life in America. But a storm led the ship to shelter in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where it is said friends convinced him to stay.

Foulis worked on technical aspects of coaling and steam ships. One foggy evening, he took a stroll along the shore and noticed that the lower notes sounded louder that the higher and carried better through the fog.

It’s said that inspired him to design a machine that would sound loudly, and with a low note, to warn ships away from the shore when the lighthouse was not visible. His first foghorn was installed in 1859.

The siren softens. It is truly beautiful

Extract from The Foghorn’s Lament: The Disappearing Music Of The Coast by Jennifer Lucy Allan

The foghorn blasts.

I don’t hear it only with my ears. I hear it with my whole body – stomach, skin, bone and skull all rattle when the foghorn sounds. The seven full seconds of its sounding feels like much longer, my guts buzz and ears hum – a flood of terrific sound ripples outwards. It is like standing next to a bass bin at a drum and bass night, only with no tops, and no rhythm. I feel the vibrational bliss and rush of physical sound.

I trot down the steps in between blasts to get a better view. From outside the horn building, even just a little distance away, the Sumburgh siren softens to a truly beautiful sound. It has no gruffness or grunt like the Souter Point diaphone, but is a velvety monotone that pours around the buildings on the headland.

Sumburgh has a seven-second blast, but other foghorns are different, with longer blasts, shorter gaps or with two notes. They were each given their own voice – a pattern of timed blasts and silences, known as their “character”. Lighthouses already had characters, meaning their lights were made to flash in a unique sequence, in order to make navigational aids distinctive, so you could reorient yourself along the coast if fog or darkness had you temporarily lost.

When a foghorn was installed, a notice to mariners went out, informing them of the sound and its character, and it was added to the Admiralty’s List Of Lights And Fog Signals, which lists, in codes, the timings of the flashes, beeps and blasts of all coastal navigational aids. So, for example, when a foghorn was installed at Toward Point on the Clyde in April 1908, a notice went out stating that a reed fog signal had been installed, that would give one blast of three seconds duration, every 20 seconds.

It’s often said that every foghorn was unique in this regard, each one completely individual, but this is a myth.

The Foghorn’s Lament: The Disappearing Music Of The Coast by Jennifer Lucy Allan is published by White Rabbit

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© imageBROKER/Shutterstock

© imageBROKER/Shutterstock © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM