This week is Real Bread Week – the annual celebration of real bread and the people who make it.

Chris Young, who has co-ordinated the Real Bread Campaign for 11 years and written many books about the subject, tells Tracey Bryce the Honest Truth about our love of the loaf…

What is bread?

You can make bread from just flour and water, though you probably want to throw in a little bit of salt as well. Work this together to make a dough, roll it out and you have flatbread. Alternatively, you can nurture the yeasts and bacteria naturally present in the flour to create a sourdough starter, or use baker’s yeast, to make the dough rise. Additional, natural ingredients can be used but aren’t necessary and if additives are used then what’s being made isn’t bread.

When was it first made?

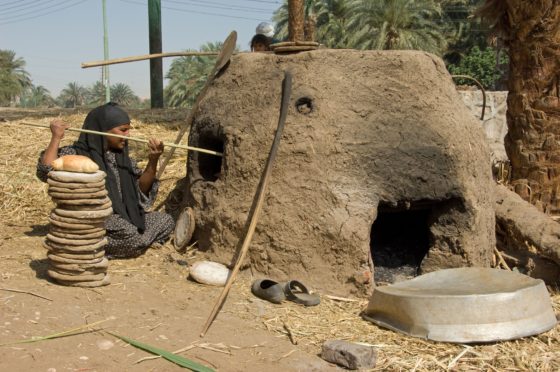

The origins of bread lie so far back nobody knows for sure. It’s generally believed the first breads were made in The Fertile Crescent, which stretches from what is now Egypt, through Israel, Jordan, Syria and southern Turkey to Iraq and Iran.

Until recently, the oldest known evidence of bread-making came from 9,000 years ago in what is now Turkey. Then, in 2018, scientists excavating a site in Jordan found charred crumbs of what they think were flatbreads made from a mixture of ground wild varieties of wheat and barley, mixed with plant tubers. They were dated back 14,400 years.

Where did the name “bread” come from?

Etymologists believe the words bread and brew are of Proto-Indo-European origin, from a root that means boil or seethe, on account of the bubbling during fermentation.

Bread is related to German brot, Dutch brood and Danish brød and, up until some time in the 12th Century, the word in Old English seems to have meant a piece, bit or crumb of food.

Before that, the word for bread was hlaf, from which we get the word loaf, which is related to Russian chleb, Swedish dialect lev and Finnish leipä. Hlafweard (loaf ward, or one who guards bread) is the origin of the word lord.

Is bread good for us?

Bread, yes, but we have our doubts about additives used in ultra-processed industrial loaf products. We also believe there are natural ways to improve the nutritional value of bread and to enable more people to enjoy eating it. The variety of grain and how it is grown can lead to higher levels of vitamins and minerals; different milling techniques can retain more of the fibre and micronutrients in the flour; and the way you turn that flour into bread might improve the benefits from eating it.

What is the “upper crust”? And the “crumb”?

We all know the outside of a loaf is the crust but it’s probably less well known that the bit in the middle is known as the crumb. Some bakers refer to the end of a loaf as the heel. As for upper crust meaning the gentry, there is no real evidence of the supposed medieval practice of slicing a loaf across to serve the top part to people higher up the social scale, leaving the bottom for servants.

What is a baker’s dozen?

Although medieval trading standards were virtually non-existent, when it came to bread pricing, they were strict to the point of bakers being dragged through the city of London on hurdles for selling underweight loaves. This is the main argument cited for one of the most common stories told about bakers throwing in an extra loaf for every 12 sold to avoid getting caught out – what we all know as a baker’s dozen.

Where does the sandwich come from?

Well, it almost certainly wasn’t that of the commonly-cited John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich. Given that bread had been around for millennia, it seems highly likely that people had come up with the idea of putting things between two slices of it long before the 1760s.

What’s the Real Bread Campaign?

Co-founded in 2008 by Scotland-based baker Andrew Whitley, the Real Bread Campaign works to find and share ways to make bread better for us, better for our communities and better for the planet.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe