THIS is the 40th year since the release of The Clash’s London Calling.

Malcolm Wyatt, author of a new book about the band, tells Murray Scougall the Honest Truth about what made the collective of Joe Strummer, Mick Jones, Paul Simonon and Topper Headon so special.

What is your background?

I’m originally from Guildford, Surrey, home to four of my favourite new wave bands – The Jam, The Members, The Stranglers and The Vapors.

I worked in a succession of office jobs before retraining as a journalist in the mid-90s. But I always wrote, self-publishing my first music fanzine as a teenager.

Why write about The Clash?

Of all the bands I loved, The Clash’s stance, look, lyrics and musical hooks soon resonated, never really leaving me.

What is your earliest memory of them?

I loved them from around the age of 11, from flicking through Smash Hits. The first album came too early for me, so I’d say it was hearing Tommy Gun in late 1978, then discovering their second LP, Give ’Em Enough Rope.

What made them so influential?

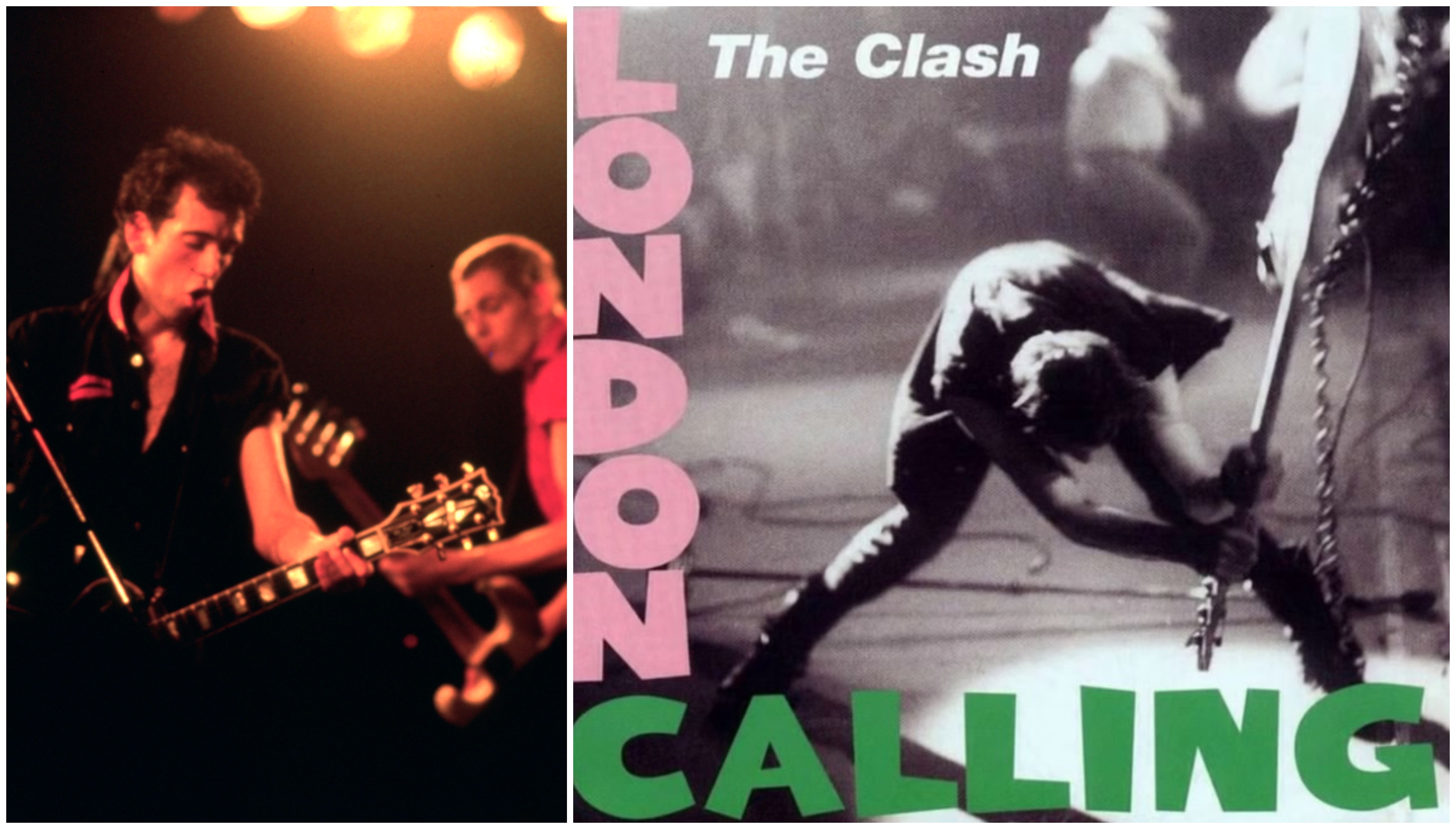

On stage, in the studio, and on camera, The Clash were inspirational, and while it’s fair to say they weren’t the greatest musicians at first, that was part of the appeal. You felt you could follow their lead, however effortlessly cool they looked and sounded. Even now you can listen to Strummer’s interviews and stage banter and sense the impact he created.

Did their politicised lyrics and rebellious attitude add to their popularity?

At times, they were frustratingly vague or contradictory in dismissing all they disagreed with, but oh for that youthful arrogance from today’s bands. Their political leanings certainly impressed this lad from a suburban council estate, championing environmentally-sound, anti-big business, anti-nuclear and anti-racist causes and initiatives.

What made London Calling such an iconic album?

Much as I love the second LP, and great as the first was, the third took the band to a new level with its heady mix of rock’n’roll, reggae and much more. All four members were key to the vibe captured, that increased confidence and fresh spirit encouraged in the studio by maverick producer Guy Stevens and engineer Bill Price bringing out the best in them.

What caused them to break up?

I’m not sure anyone can withstand the pressure heaped upon bands that tour and play so hard – in more ways than one. When Headon’s drug dependence took its toll and Jones’ volatile relationships with Strummer and Simonon needed a little in-house diplomacy, it wasn’t likely to come from reinstated manager Bernie Rhodes.

Had Joe Strummer not died in 2002, do you believe they would have eventually reformed?

Anecdotal evidence in recent years from bandmates and key associates suggests it might have happened, and Strummer had something in mind, with Jones’ input. But when Strummer died, Headon was still some way off recovery and Simonon admits he was the most resistant to reforming.

Does their music remain important today?

It does, and so many later artists picked up on that vibe and took it elsewhere. There won’t be another Clash, but their spirit lives on through many other acts, and that’s been the case since the likes of Dunfermline’s Skids were inspired to carve out careers.

How will they be best remembered?

As well as their music, they were a fashion statement and a subcultural “go to” barometer, inspiring us to check out politics as well as funk, reggae, rock’n’roll, ska, hip-hop and soul.

Nothing was off limits if it moved you and was passionately delivered. That kind of enthusiasm and all those great songs ensured this was a band that really mattered.

This Day In Music’s Guide To The Clash is out now.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe