THERE are only a handful of Scottish political leaders whose names truly resonate across the decades.

Most are Labour. Tom Johnston, the Red Clydesider who became Churchill’s wartime Scottish Secretary and who created the North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board that brought electricity to the Highlands.

John Smith, who returned his party to electability and who but for his tragic early death would have made it to No 10.

Donald Dewar, who piloted the legislation to create the Scottish Parliament through the Commons and then became the country’s first First Minister.

And Gordon Brown, powerful Chancellor of a three-term government, who as Prime Minister rose to the global challenge posed by the financial crisis.

The SNP hasn’t yet produced one of these leaders: a figure whose achievements and reputation place them above the prejudice of party politics.

Alex Salmond won two Holyrood elections for his party but showed little interest in producing transformative policy for the country; and he lost the independence referendum. His predecessors are largely of interest only to SNP historians.

Nicola Sturgeon had – and perhaps still has – the potential to be different, and earn herself a place in the pantheon.

She is a politician of surpassing gifts: a commanding orator, a keen appreciator of the nuts and bolts of policy, the single most-important player in the overdue feminisation of Scotland’s macho political culture.

She is emotionally intelligent, morally driven, has a sharp sense of humour and is no stranger to self-deprecation. She reads books and draws lessons from them, a rarer quality in politics than one might expect. She is unchallenged as the pre-eminent figure in her party and government (as one SNP MP put it to me last week, “if something happened to her tomorrow who would step in as leader? Who fills those shoes? I have no idea”.)

She pretty much has it all, then. And most impressive, I think, is her capacity for personal growth.

Sturgeon was a shy and introverted child who spent her fifth birthday party hiding under a table reading, as her friends played ring-a-roses.

She admits, she “wasn’t particularly outgoing… and I was like that through my teenage years.”

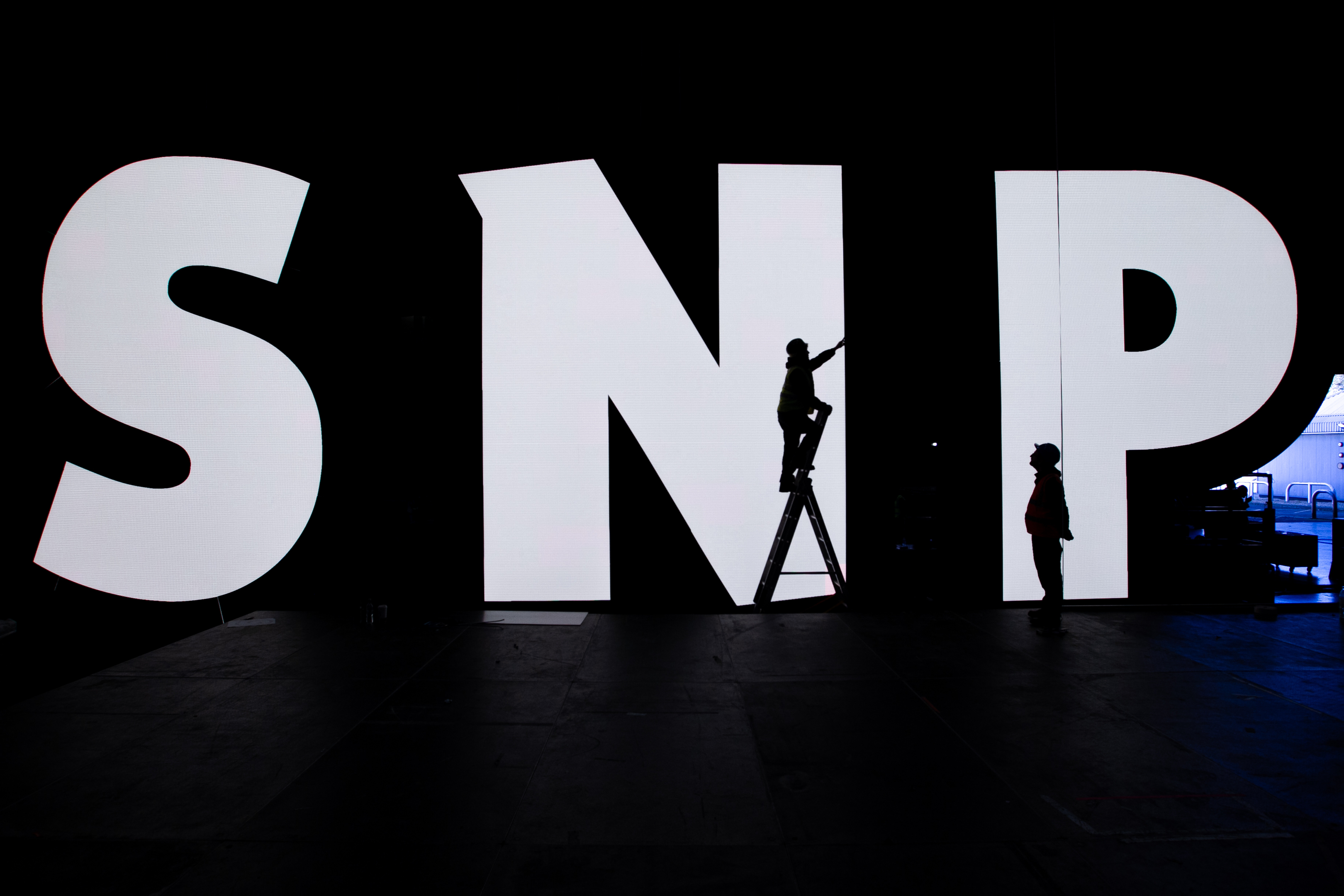

In her early days as a politician she was “quite po-faced and serious. Too serious”. The woman who, mistress of all she surveys, will confidently deliver her set-piece speech to the SNP’s conference in Glasgow this week has been on quite the journey.

But there is one thing standing between the First Minister and true historical importance, one flaw that threatens to limit her to the ranks of “good but not great,” and it is nothing to do with whether she secures Scottish independence or not – it is her caution.

Sturgeon gives the impression of being allergic to risk, perhaps even of being scared of failure. And while caution is in some ways and on some occasions an admirable trait, there are times when a leader must go for it – pick fights where they really matter, win them, and be willing to make enemies along the way. I don’t doubt the First Minister’s head and heart are in the right place.

I’ve talked to her and the people around her often enough about policy to know that on education, to take one key issue, she knows what needs to be done to improve our under-performing schools.

Her problem is that the only way to bring about this long-overdue change is to go to war with Scotland’s protectionist education establishment: the General Teaching Council, Education Scotland, and the EIS, Scotland’s main teaching union.

As the former SNP deputy leader Jim Sillars put it to me last week, “reforming education means taking on vested interests like the EIS, which is one of the most conservative institutions in the country. That requires courage but the government has retreated.

“That’s a real sign it can’t find the will to examine an issue, come to a conclusion and drive it through.”

Sillars is no fan of Sturgeon’s leadership – she “is more of a technocrat than a leader with the kinds of qualities required,” he says – but in a series of conversations over the past week I found his analysis is shared even by supporters.

To quote a senior member of her party: “She is more strategic where Salmond was tactical, but that meant that Salmond was on it every minute, driving the agenda.

“She is longer term but that can make it seem like she’s letting things happen to her. She’s got to drive herself. Everything is in her favour, there were some good things in the Programme for Government, but she’s not following through.”

And James Mitchell, professor of public policy at Edinburgh University and a leading thinker on Scottish nationalism, said: “There are so many deep-rooted policy challenges around the economy, demographic change and so on. I think there’s a tiredness there, and a bit of timidity. What they need are new ideas, but they seem frightened of their own shadow.”

In the end, independence is not in the First Minister’s gift, and those expecting some big announcement on the issue at SNP conference seem likely to be disappointed.

But there is much that is in Sturgeon’s control – choices that only she, with the might of her office, can make. She finds herself at the helm at a time when the world is convulsing and shape-shifting.

Britain is leaving the EU, power is shifting from the West to Asia, and we are only in the foothills of a technological revolution that will transform the way we live and work. A little boldness is essential if Scotland is to take advantage of this change.

In short, take some risks, First Minister. Give us something to remember you by.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe